When I was a child, the place where I lived was essentially bounded by wilderness, the lake on one side, the enormous dark green wings of the Purcells above. Our small farm was in the southeast corner of BC, on the edge of the huge, deep Kootenay Lake. The farm seemed huge to me as a child, endless, in fact.

The mountains above the farm had not been logged — there were no roads except the highway. I was a kid driven by curiosity and restlessness and so, at an early age, I set out to learn where I lived. Of course, the first thing I discovered was the lake, the giant magical deep expanse of Kootenay Lake, and the gold-sand beach below the farm, bounded by smooth fissured granite. Above the farm were range on range of mountains. There was room for unlimited exploration.

As a very small child, I knew the house and my mother’s steady presence in it, almost always in the kitchen. My father was working in a mine at the time, so I didn’t know where he went every morning, his black lunchbox swinging at the end of his long arm.

But we moved to my grandfather’s farm when I was five and my father was home every day. I followed him around and naturally enough, I became a farmer. My first job was looking after the chickens, especially the new baby chicks, which came in a box from the guy at the grain elevator, tiny balls of golden fluff that peeped for their mothers. I put them under the red light of the heat lamp, made sure they could find the food and water. As soon as they had grown pin feathers in their wings, I could open the small door in their shed, and let them out into a fenced space. I would sit by the door and coax them out, one by one.

But there was a much wider world beyond the lake. Soon I knew the seven miles of road between our farm and the small one room school we went to. I also learned this road intimately because twice every year, we chased our cows the five miles to the river crossing and swam them across to graze for the summer in the swampy wetlands. In the fall, we brought them back just before it snowed and the river froze over. This meant running through three miles of swamp to round up the cows, bring them back, and run the five miles home to the farm. I knew the swamp from the tunnels the cows made through the willow brush where we had to crawl on our hands and knees to get through.

When I was seven, I got a fishing rod for my birthday and that gave me a new way to learn the lake, the wind, the rocks, where to throw a bobber or a lure, and when. Fishing was a way to sit still, watch the water, and how the light changes through the day. In summer, I always wanted to sit on the warm rounded granite of the “fishing rock,” until the light faded over the flat royal blue of the evening mountains, and listen for the evening downdraft, wind falling down the mountain, bending the tree tops and talking to the leaves.

I also learned to bicycle on my own the three miles to Kuskanook where Alan, my best friend from birth, lived. He had comic books which our father didn’t allow us to have. He thought they were a silly waste of time.

As I grew older, I walked farther, I bicycled farther. I found cliffs that were almost unclimbable and I climbed them. In the right season, I swam, I fished, I ate out of the garden and the orchard. Almost every weekend, especially in the spring as the snow was leaving and the forest opened, I would take some matches, a hatchet and a can of beans and set off. Sometimes I went along the lake front, sometimes I went straight up the mountain, whatever called me. By the time I was ten I knew, intimately, the mountains, the marshes, the lakeshore, the river, the neighbours, for about seven miles on either side of our farm. I knew the trails, the changing light, the smells, tastes and above all, sounds of everything and everywhere. Sound is a crucial element when you’re out wandering.

I was a very feral child and what I most wanted while on my own, to avoid was other humans. I spent my summers mostly either working on my own high in a cherry tree or bent over thorny raspberry bushes, and finally, when the work was done, heading on my own to the lake shore or up the mountains. Interacting with people always felt difficult and awkward.

It is a somewhat cliched saying in therapy that the map is not the territory. Polish-American scientist and philosopher Alfred Korzybski theorized that “the map is not the territory” and that “the word is not the thing,” because he believe that people confused models of reality with reality itself. It’s also a staple saying in neurolinguistic therapy. It has truth in it. In an article on neuro-linguistics, John David Hoag states, “No map is ever completely true. Maps are static analogs, like a snapshot, while territories are dynamic, like a river. Maps can become outdated. They may be resourceful at one time in our lives and limiting at another.”

But there are many kinds of maps. Sometimes the map becomes the territory in a very specific way. And a territory becomes a map, and if you flip this idea around, the territory can become a map that is essential to a full understanding of identity.

I am a senior adult now, and have been a writer most of my life. Lately I have been tasked by my community with researching the history of this region where I live. Of course, this involves looking at a lot of old and new maps. Plus part of the research includes the history of the local First Nation, who don’t have maps but have their own names for all the places on the other maps I have seen. One of the members told me that the names of places hold stories about when the right time is to hunt, or fish or gather berries there.

So I have been thinking about how these First Nations people once travelled and moved with the seasons, how much and how intimately they knew the land they lived on and how they held their maps internally. Most First Nations people travelled a lot, some were nomadic, many were not, but almost all tribes and Nations traded with each other, negotiated deals, treaties, gathered to share stories and food. They didn’t have maps. What they had was knowledge of where they were and what it looked, tasted, sounded, smelled like, in every season, where things were and how they grew.

At seventy-four, I live in a town now, instead of on the farm where I spent most of my life. When I moved to this town, I realized I didn’t really know where I was. I knew the main street, some buildings, my friends. But I had no sense of it as a place, as a sensory map, as a place to live in, a place to truly know.

I have two big dogs, and they were displaced as well, confused by living in a place with so many bewildering new rules, where they couldn’t run up to any dog they saw to see if it wanted to play, or run up new humans to make friends, as they were so used to doing at the farm. They were trapped in a luxurious kind of jail and so was I.

I began driving out of the town to take them for walks, exploring trails and paths I heard about from other dog people. I tried, as much as possible, to avoid trails with a lot of other dogs. And, because I am physically crippled from rheumatoid arthritis, and also have a heart that doesn’t like to walk uphill, the trails I can walk are limited. No more running up mountains for me.

A friend whose book I was editing came to my rescue as my adventure buddy. I love adventures too; but as a very crippled-by-arthritis adventurer, having a helping hand occasionally is important. Plus she has an old and wonderfully slow boat. We drove down roads, climbed rocks, explored the Goat River, the Kootenay River, and Kootenay Lake and the river by boat and on foot.

With great good cheer, she helped me over rocks, and down embankments, and through thick brush. With her help, my sense of adventure returned.

And when I was commissioned to write the local history of the town and surrounding area, I grabbed the opportunity. I love history of any kind so this was an amazing opportunity. I also teach memoir writing and I tell the people I mentor that they are also historians, recording important stories that future generations will cherish.

Now I am learning the geology of the valley, the names of the birds, the history of the dikes that closed in the Kootenay river, along with stories of the First Nations I never knew. This has broadened my perspective and given me a new and bigger interior map.

For me, knowing land, having an internal map, not just of the land but all of its sensory offerings in every season is crucial. My brother is similar. The few times he and I went to the big city together, he would immediately disappear, walking to find the ocean, the streets, the parks, landmarks until he had some sense of where he was.

Now I feel, tentatively, that I am beginning to live “here,” although I can’t climb the mountain above my house which would help. People ask me kindly if I have adjusted to living in a town. “No,” I say truthfully, and I never will. But I am making a bigger map and that has its own satisfaction.

I think very few people really know where they live, all the many dimensions of a place, historical, seasonal, geological, sensorial. I taught a class once in Vancouver about a sense of place and one woman began to cry. “I don’t know where I live,” she said. Most people in cities don’t, there’s no reason why they should. Modern industrialized places allow people who live in them to move without thought, and with bare knowledge of where streets and stores are. And of course, now there is Google and GPS.

But I have tried to imagine how much, for all First Nations, knowing the interior maps of where they lived was crucial to their lives, to finding food, to survival. Knowing the history of what had happened meant that every rock and tree and creek and mountain had a story. Everybody had these interior maps laid down in detail along with the stories. The elders were so crucially important because they were and are the story keepers, the culture keepers, the living maps.

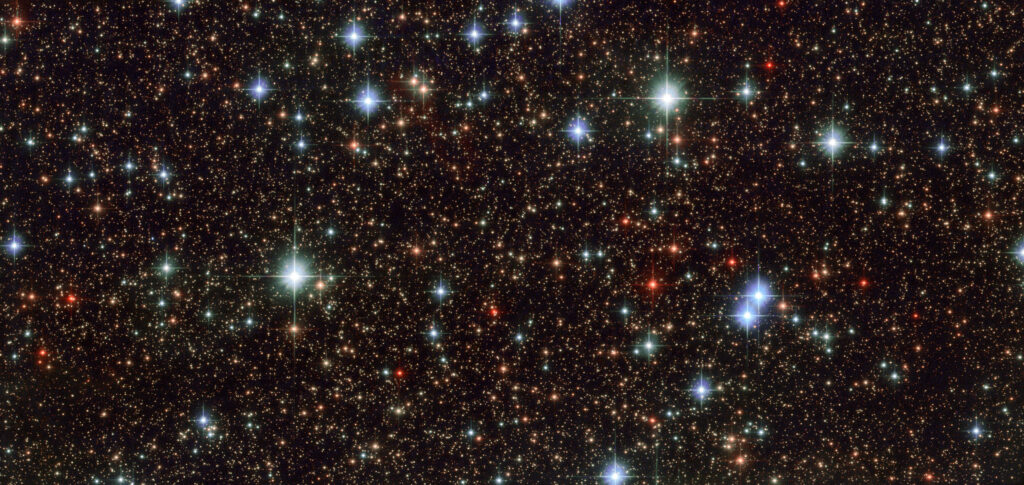

So for now, staying in and not walking for me is not an option no matter how slow I become. And knowing my “place” is crucial to my life as well. I’ll keep on, as long as my legs let me, turning ‘my’ territory and its history, into a map. This interior map has depth and dimension, sensory memory layered in depths, layered in perception. It is four dimensional because it was built over time and continues to be built. It has no edges; it expands infinitely, endlessly minute in detail, and one day it will map the stars which I am sure I will reach, one day soon.

You are already the stars you know you will someday be among. In the small town South of the United States, we call that “done already.”