Peter: Will I ever see my daddy again?

In my work I don’t travel much. Only a rare two- or three-day conference will keep me away for any length of time. Moreover, many years ago, when my four sons were young, whenever I did leave town, it was usually only for a day trip, and I’d make it home by their bedtimes, if not earlier. One summer, however, I was gone five nights in a row for two successive weeks, and my preschool third son, just two days in, was already wondering if I’d ever come home.

I could have cried when his mother replayed all this long-distance.

And then she raised the stakes by relaying what Peter had been absent-mindedly bemoaning to the tune of a current Red Hot Chili Peppers hit, “Sometimes I feel like I don’t have a… daddy.”

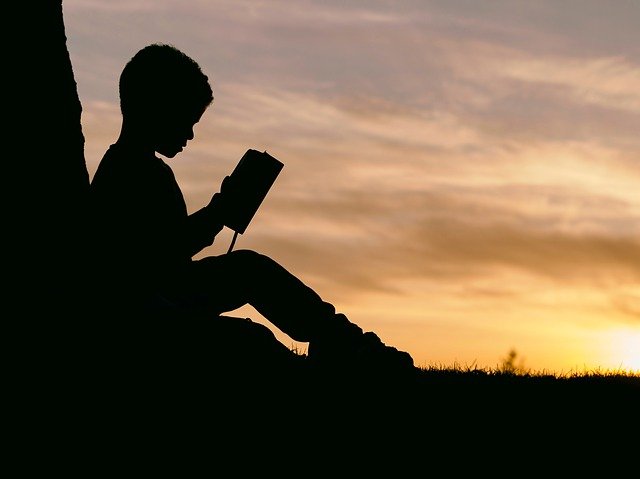

“I was just doing laundry,” she explained, “and there he was in the sewing room, lying on his back, one pudgy leg crossed over the other, wailing this top 40 hit to the acoustical ceiling.” Lamenting his father’s absence.

How could he have forgotten I always came back? Sure, he was just a little kid, but when had I ever given him reason to doubt my return?

My own father was a very absent traveling salesman when I was growing up. He’d often leave early on a Monday, often before I was awake, and not return until Thursday, often after my bedtime. As I recall, I never thought much about it. That’s just what my father did. Perhaps I thought that’s just what fathers do. In any case, I don’t recall begging to stay up long enough to see him or rushing to meet him when he did come home early enough. Though that’s what my kids did when they were little, especially Petey.

I also know I never sang songs about my father’s frequent absences. In fact, if anything, I believe I noticed how much more smoothly the household ran when he was gone.

“Can I talk to Peter?”

“Sure. He’s right here.”

“Hi, Petey…”

“Hi, Daddy…,” and his apprehension seemed to melt away.

“How ya doin’?”

“What? Good! I’ve been doing lots of working and Michael fell off Caroline’s wagon and got two Mickey Mouse Band-Aids and….” He chattered on and on about extension cords and ladders and drywall and Greg the electrician—Peter: Future Handyman of the Year, in his element as the work proceeded on our family-room addition.

All he seemed to need was to hear my voice.

I was especially moved by this because long-distance calls from my dad when I was a child were routine and mostly plain inconvenient when they drew me away from my early-evening TV shows. I was so used to his being away that his calling didn’t reassure me of anything I thought I needed. Perhaps it did for him, but my recollection is that his calls and our formulaic conversations seemed routine to him as well.

When my dad was home, our relationship wasn’t that much more significant. Being the business-quotas kind of man he was back then, with the uninvolved kind of father he’d had as a kid, coupled with the expectations generally for family men in his era, The Greatest Generation, he just never felt terribly compelled to get involved in my life.

It’s no wonder I didn’t sing the blues till he called.

Once I was old enough to notice how a few of my friends’ fathers actually were involved in their kids’ lives—playing catch, coaching little league, attending parent-teacher conferences—and once I could imagine a little later on how I myself would father to break the familial cycle, a great sadness set in and grew. Even today, as I write, that sadness temporarily sets in again, a sadness that could inspire my own chorus of “Sometimes I feel like I don’t have a daddy.” In his later years, retired, my dad was available to me all right, albeit in another state, and a fine man in his own way, but in many other ways I never had a daddy. And then, surprisingly, his death crushed me with the added realization that now I never would.

I guess I finally knew, to some degree, how Peter Chili Pepper could have felt like he did before he heard my voice.

When I studied the Psalms as a young father, I guess I also knew by analogy how David must feel. So often he wonders if his Heavenly Father (which was how my patriarchal church culture always referred to God) has forsaken him—if his Father will ever speak to him again. Many people have wondered, do wonder, this. If they’ve not wondered if God even exists, they’ve wondered why their “living” God won’t speak to them, answer their prayers, get involved in their lives, act like their Daddy.

Peter, of course, had cause to ask his question and sing his song: he was a child who didn’t know better, even though his father had always come home before. But at that earlier time in my adult life I would have said—and, in fact, still did say in an earlier version of this rumination—that David, or any adult child of God, has no cause to question—neither the excuse of childish consciousness nor the excuse of the absent Father. I would have pointed out the orthodoxy that through God’s actions in all of history; through God’s incarnate Son’s ministry on earth 2000 years ago; through Jesus’ on-going gospel of salvation and gift of peace in the Holy Spirit; and through the revelation of God, historically and personally, in His Word—through all these, children of God can find the evidence they need (if they truly want it) that He longs for them to experience His Presence and hear His Voice.

When I studied the Bible, knowing these “facts” in my mind and, I believed, somewhere in my spirit, I thought I heard God speaking to us—to all of His children—through His general revelation of Truth. These were the truths that believers (and nonbelievers) could study, that ministers (and conmen) could preach, that commentators (and manipulators) could explain.

And also when I studied the Bible, I thought that I sometimes actually heard God speaking directly to me, often in a fresh way from a familiar passage, revealing truth for that moment in time. Then, not only did I think I’d learned how to get on with my life as God would have me, but I thought I’d received assurance that I had a loving Father who heard my voice and wanted me to hear His.

Eventually, though, a larger-than-sometimes-manageable measure of uncertainty about “God’s Voice” crept in, making it nearly impossible for me to think and say what I so easily used to think and say about how clearly one can discern God’s Will. Life got complicated. My church was sounding more and more dogmatic, exclusive, as I was becoming more and more open, inclusive. My sons’ mother divorced me—to me, out of the blue. And the resulting single life after twenty years of marriage, the partial separation from my kids, and the financial hardship brought on latent depression, unbearable sorrow, and a sense of existential pointlessness.

Søren Kierkegaard’s powerful book Fear and Trembling has helped me more recently to consider the uncertainty that I’ve come to feel. This odd work of philosophy, which some call a “dialectical lyric” because it speaks through the more poetic than philosophic voice of Johannes de Silentio (John of Silence?), focuses in nontraditional ways on the Old Testament’s Abraham—in Kierkegaard’s words, the great “Knight of Faith.”

The sum of the book stands in awe and praise of Abraham’s inexplicable faith, especially as it operates in the story of his willingness to sacrifice his only, and promised, son Isaac in obedience to God. Kierkegaard’s Johannes explains how a hero—such as the tragic hero of ancient Greece—would somehow have either defied such a command of God, since it contradicted all other notions of how God would want us to deal with our loved ones, or submitted to God out of sheer obedience and resignation, fully knowing the contradiction such an act would demonstrate but committing it anyway and surrendering to the terrible consequences that would surely follow, all out of pure personal strength and blind loyalty to the divine.

But Johannes calls Abraham not a hero but a Knight of Faith, one who obeys, no matter the seeming contradiction, and believes God’s promises nevertheless: in sacrificing Isaac, Abraham still believes he will retain his long-promised and long-awaited son who is to continue the family line and engender the promised people of God. Abraham believes he can lose and have his son, can eat and have his cake. He has unswerving faith in God, not a heroic will to self, and thus the Knight of Faith far surpasses the tragic hero.

Now, being such a knight would be great, and Johannes agrees, but he also says he isn’t anywhere close to having such a faith: “I cannot close my eyes and hurl myself trustingly into the absurd; for me it is impossible” (63). Johannes can’t get past the paradoxes of God, or at least of God as God is commonly revealed to us. Johannes might rise to be a hero but never a Knight of Faith. He confesses:

When I have to think about Abraham I am virtually annihilated. I am all the time aware of that monstrous paradox that is the content of Abraham’s life; I am constantly repulsed, and my thought, for all its passion, is unable to enter into it, cannot come one hairbreadth further. I strain every muscle to catch sight of it, but the same instant I become paralyzed.

In the margin of my copy of the book I at some point wrote “Amen!” for it perfectly captured and still captures my frustration—even existential despair—with this and all the paradoxes of life, let alone of all of scripture.

In his 1997 Perspectives article (yes, I’ve been wrestling with this for a while!) “The Toothsome Scriptures,” Keith Titus seems to have found a way to live with paradox. While God at times seems to boom forth in scripture “in no uncertain terms,” and at other times seems quite obviously to contradict Himself, Titus actually loves the paradoxes. I would imagine he’d agree that the case of God’s demand of Abraham to sacrifice his son raises an insurmountable paradox. In particular, Titus points out the paradox of God’s commands, for example, both to make one’s light shine before others and to keep to oneself when praying and doing good works. Titus cries out to God, “Do you want me to do this or this?”

What’s oddly aggravating, says Titus, is that God answers, “Yes!” But rather than falling into the despair that I am now (and Johannes is) prone to, Titus responds, “I love the struggle, and I love the God who gives us the freedom to grapple with the truth of our lives. How much more fulfilling to hunt for God in thickets of words…finally to break through to one ripe fruit and take a bite, all the while praying that the fruit is from the right tree.”

My Petey shouldn’t have needed to wonder if he’d ever see his daddy again, the daddy who’d always come home before, but he did because he was a child. All he needed, though, was a well-timed phone call and to hear his daddy’s unparadoxical voice.

David—it would seem—shouldn’t need to wonder if his Heavenly Father will ever make His Face to shine upon him and give him peace, which he continually rediscovers for himself and celebrates in plenty of other psalms. But he is a “child,” too, who only needs to hang tough, in faith, often in the midst of paradox, as he has so many other times, and trust God to reveal Himself—His Voice—in some special way, as He apparently always has before.

And children of God today—it would seem—shouldn’t have to wonder if they’ll ever hear their Father’s Voice for the clarity and assurance they crave, especially in the face of paradox. God is constantly seeking them out, supposedly, making moves to establish relationship, and God’s Voice is, supposedly, always on the other end of the line of God’s Living Word. The Word of God, after all, is the Voice of God: people claim that it speaks clearly and uniquely and reassuringly to whoever will listen with ears that hear.

Ears that hear, however, seem to operate more rarely than some might think. Available to all, perhaps, they nevertheless can be deafened by the too-slick view of scripture that considers the Bible, in Keith Titus’s words, as “a sort of Cliff’s Notes for life or, worse, as a kind of self-help manual, which distills centuries of Jewish and Christian struggle into a reference book of aphorisms and adages that answer all of life’s problems…. You just quote chapter and verse, black and white, and never mind the shades of grey.”

I know at least that I’m not that kind of deaf. But I’m less certain that I could ever become Titus’s lover of paradox thrashing around in God’s “thickets of words.” And, with Johannes, I, too, risk annihilation in contemplation, let alone imitation, of the Knight of Faith.

So, what of the Father’s Voice?

I’ll be honest: most times I feel like I don’t have a Daddy.