My grandmother Lilly grew up just light enough to pass but not to matter. She married at thirteen, made her life a torch of love and raised eight babies on nothing but what they could scratch and raise and kill.

When she buried a husband in her 60s her children all said Come live with us, but she said no. Instead, she bought a used trailer, first house she ever had with a bathroom, and moved it around: Gastonia, Indian Trail, Green Creek, in and out of the little side yards of people who had reason to love her.

Aunt Lena’s husband died in a fiery crash. She had a baby in her arms and one in the belly. A handsome sinewy whiskey-drinking woman of the hills, she had other offers to marry but said no. Do it twice?

Lena kept an oiled rifle near to hand. She lived by a trout stream and took her water from a spring, ate more wild meat than grocery goods. She made squirrel dumplings that drew the neighbors like pollinators to a hoorah bush. Taught school for 40 years with all her heart, went home to meet her Jesus sanctified, bending under the waters of the Primitive Baptist Church when she was eighty, just in case.

Mrs. Cantrell lived down an off-lane near the end of our dirt road, a sweet cottage with a shaded porch under tall cool cedars, not our chaos but a place where everything had a place. My father took her to church and I used to visit her, bent gnarled kind shy, with a game laid out on the table when I came by and parched peanuts baking in the oven.

She held both my hands whenever I left, as if to calm a stray animal and turn it loose. When she died I wept into the black telephone, a grown man a thousand miles away.

Watching the pasture now that divides my two nearest neighbors, widows living in houses they raised a family and endured a husband in, alive, wily, come into their own. Maybe I can go sit with them today, carry some sweet corn and shuck it while we get to the importance of what’s happening in the neighborhood, in our families, in the ground.

I’ll say this: sometimes a woman has a seed of waiting imbedded in her by circumstance and blood, her life a long exhalation of birthings until the last one out of the canal is herself alone. Sufficient and reveled in solitude.

How I love and cherish them. How I have followed them all my life.

~

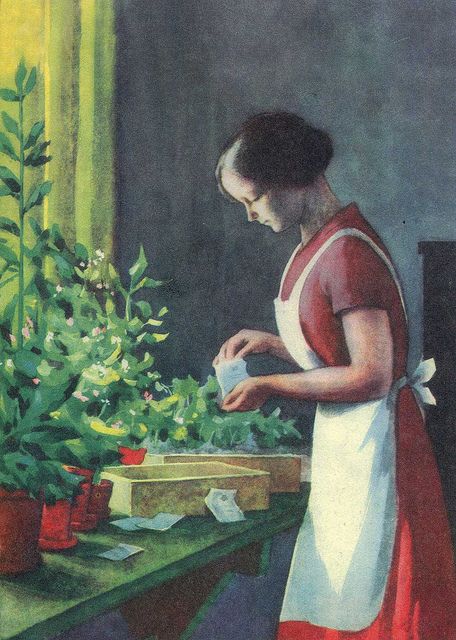

Painting by Rudolf Koivu.

What a poignant portrait of women. The stories brought to mind Cousin Mattie Mathis who we picked up for church —a widow in her 80s, and My Aunt Ruth who lived alone in a farm hoping to die tending her camellias!

Hi Gary, I totally enjoyed reading this piece about your strong women ancestors and was taken with the line… “her life a long exhalation of birthings until the last one out of the canal is herself alone.” I want to share this piece with so many. Keep writing! You are a true poet.

I love reading your work, I am 88 years old and recently published a book,

Your poetry is so relative to my memories.

Montress, thank you!

Thank you. Great to see your comment.

Love this, thank you Gary

Lucky person to have such women in your life, as well as the heart and wisdom to really see them, even as a child. Your beautiful words made me think of my Great-Aunt Lizzie, only daughter, who lived with her parents and cared for them while her brothers married and started new families.

Gary, I love your view of these strong women. What a beautiful piece! Thank you!

I am so pleased with these remarks, so grateful.

Blessings on all the strong independent women in your lives.

That was wonderful. Thanks.

I truly love your writ memories, Gary. -So unabashed, warm, so Human… so you.

A friend shared this with me a few moments ago. What lovely thoughts and memories were put into this Living Alone – Braided.

Beautiful beautiful tributes that celebrate the kind of women that shaped our families and our sensibilities. Your mother, mine, our Aunt Lena.

Thank you so much, Yvonne! I’m glad I did them service.

Love,

A lovely, intimate piece that conveys so much in so few words. It is especially poignant as it is written by a man. I printed your piece out so that I can read it again and again. Thank you and don’t stop writing, Gary!