“Before there was the Word, there was the land, and it was made and watched over by women.” –Sharon Blackie

As a researcher of women’s spirituality and the Sacred Feminine, I’ve spent years diving into the little known, yet rich her-storical record that documents Her existence in cultures around the world. And admittedly, this exploration has made my brain extraordinarily happy. Always lurking in the background (and often in the foreground), however, has been a keen desire to get to know the Sacred Feminine in a more visceral way, in my heart and in my embodied experience. Luckily, as I’ve come to find out, one of the best ways we can do this costs no money and requires little more from us than simply walking out of our homes and into the closest approximation of a wild space that we can find.

One of the Sacred Feminine’s most recognizable traits is Her connection to nature, specifically as our Earth Mother. To the Andean people of South America, She is Pachamama. To the Maori people of New Zealand, She is Papatūānuku. To the Indigenous Saami people of Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia, She is Máttaráhkká. Even those who know nothing about Her are still likely familiar with the terms “Mother Earth” and “Mother Nature.”

The idea of the Sacred Feminine as the Earth herself clearly isn’t new; in some ways, it seems to be as old as time itself. “Paleolithic people lived literally as well as metaphorically within the Great Goddess and were a part of her,” noted David Leeming and Jake Page in their book Goddess: Myths of the Female Divine. I’ve always believed this is the reason so many little, ancient Paleolithic female figurines don’t have feet – instead, they are like trees, their legs tapering off into some unseen root system connecting them to the Earth herself.

In Scotland and Ireland, the Cailleach – the Old Woman – was said to have made the land when she dropped a large number of rocks from her apron, and there are many landmarks named after her in these countries. She’s also associated with the waters of the land and weather, too, especially the fierce, cold storms of winter.

The ancient Egyptians celebrated Nut, the Goddess and Great Weaver who wove the world into being, giving birth to the Sun God, Ra. The Aboriginal people of Arnhem Land in Australia tell of Kunapipi, the First Mother, whose body is Earth itself. The Okanaga tribe of Washington State, too, describe Earth as the body of a woman. “Her flesh is the soil; her hair is the trees and other plants. Her bones are the rocks and her breath is the wind. She lies, her limbs and body extended, and on her body we live.”

The ancient Greeks gave us the story of Gaia, the Earth and Mother of all things, who created herself out of chaos. In the Homeric Hymn to Gaia, we get a sense of the reverence that once may have existed for Her:

Gaia

mother of all

foundation of all

the oldest one

I shall sing to the Earth

She feeds everything

that is in the world

Yet even with all of these beautiful names and traditions of honoring Her, it’s been a long time since we’ve lived in a world that views nature and wild spaces with reverence. We plow Her over to make way for our cities and roads. We pollute Her sacred waters every day and pretend that it doesn’t matter. At best, we relegate Her to parks and designated areas so that we can go to visit Her – forgetting that She is everything, everywhere. At worst, we exploit Her for our own selfish purposes. And we are paying the price for our callousness, as climate change brings us ever-more damaging fires, floods and species loss.

There’s an entire body of research and scholarly thought, known as ecofeminism, which points out the parallels between the extreme destruction of the planet and the treatment of the world’s women. Penobscot activist and writer Sherri Mitchell sums up this notion quite clearly: “When we look at the history of feminine suppression, we see that it correlates directly to the destruction of life on Earth. First, men stopped listening to the voices of women, and simultaneously stopped hearing the voice of creation. Then they began attacking the wisdom held by women through witch hunts that burned and scarred the women’s flesh. This devaluing of women led to a rise in violence against women. This was reflected in outward attacks against the body of the Mother, as the flesh of the Earth was simultaneously torn, burned and raped…All of this madness is caused by the absence of the divine feminine wisdom within our societies.”

Despite our destructive tendencies, which may very well prove to be the downfall of our entire species, the tragedy and opportunity in all of this is that most of us know the wisdom that Gaia, our Earth Mother, offers us. It’s why, when asked to recall a moment of extreme peace, so many of us think of a particular landscape that calls to us. We belong to Her, and She belongs to us. No separation.

Over the years, my own relationship with the Earth has continued to deepen and flourish, and today it represents one of the most important ways in which I experience Her presence and wisdom. The land speaks, the water speaks, the trees and birds speak, and I hear Her voice in all of them. In fact, they speak more loudly to me than any book, icon or image of Her ever has.

I had a powerful experience of this several years ago, when my family traveled to Europe so that I could visit several Sacred Feminine sites for my research. In particular, we did a fair amount of finagling to make sure that I could visit the Black Madonna of Einsiedeln in Switzerland, also known as “Our Lady of the Dark Forest.” The name might seem a bit strange now – located a couple of hours from Zurich, the abbey where she is located is surrounded by open fields and grazing lands, but once was indeed home to a large, dark forest where the Benedictine monk St. Meinrad retreated to live a solitary life in devotion to the divine back in 825 CE or so. Supposedly, all he took with him was a black statue of Mary.

After spending several picture-perfect days in the Swiss Alps, we drove hours out of our way to visit the abbey where she is located. And she was indeed a beautiful sight. Positioned close to the entrance of the grand cathedral, she was surrounded by intricate gold carvings that looked like clouds, and both she and the infant Jesus were dressed in sumptuous white and gold robes, which glowed against their gleaming black skin. In the background, a choir located somewhere out of sight was singing Jeff Buckley’s version of the Leonard Cohen song “Hallelujah” in a language that I didn’t know, which was both hauntingly beautiful and somewhat strange to hear inside a church. I sat in a pew a few rows back and stared at her, trying desperately to feel the presence of the Sacred Feminine here in front of me. But in that moment, she simply looked like an elaborately dressed statue. I felt awkward and uncomfortable, wishing that I sensed some sort of power and mystery there in her presence. Instead, my mind wandered back to something that happened the week prior.

The Swiss Alps are home to some of the most spectacular scenery I’ve ever witnessed, including some truly impressive waterfalls. The week before I visited the Black Madonna, we’d gone to Trümmelbach Falls, located in the picturesque Lauterbrunnen Valley. Trümmelbach Falls are actually a series of ten waterfalls, fed by glacial run-off and flowing inside a mountain. More than a hundred years ago, a tunnel was created so that visitors could climb a series of stairs and view the falls from various points. You can expect to get spectacularly wet while doing so, because the falls are rushing with tremendous power, and the resulting spray coats everything inside the mountain, including people.

I was with several family members that day, and it was dark and cold inside the mountain. We’d almost traversed the entire walkway within the mountain when I descended a set of stairs and came face to face with another powerful gush of water barreling its way through the mountain. The sheer force of it felt like a literal slap in the face and I felt the power of it reverberate throughout my entire body.

There were vibrations inside my chest and arms and legs, and for one incredible, shocking moment, I became the water. The water wasn’t just flowing inside me; it was me, and I was it, and the fierceness of us took my breath away. In that moment, I felt, with absolute knowingness, the sheer creative force flowing through nature, and I felt my own unity with it. It only lasted a moment, but it shook me in the best possible way. And this was the moment I found myself returning to inside Einsiedeln Abbey, there in the presence of a wonderful, old Black Madonna, of whom so much has been written and who undoubtedly means so much to so many. No matter how grand the cathedral and how powerful the image, the Sacred Feminine seems to speak to me the loudest and the clearest through nature, and this is a lesson She continues to reinforce wherever I go.

“Nature is teaching us how to be human every moment of every day,” writes Rebecca Campbell. “The rose coaxes us to open and soften our heart. The oak teaches us to drop our roots deep in order to stand tall…No matter who you are, you will find your true nature in nature.” That true nature is ultimately our own innate divinity – and Her.

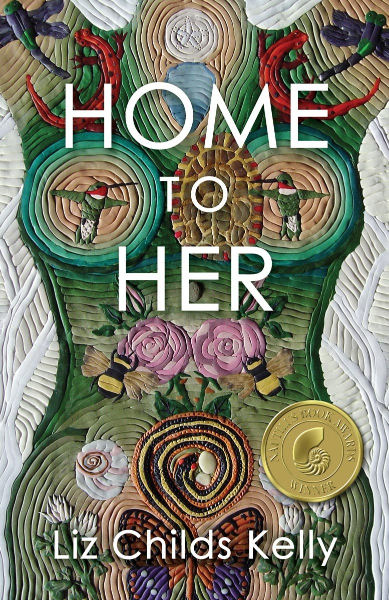

Adapted from Home to Her: Walking the Transformative Path of the Sacred Feminine (Womancraft Publishing), by Liz Childs Kelly