I call it a ghost, but whether it was a spirit or entity or traveling soul, I don’t really know. I saw her out of the corner of my eye. What I saw was a black shape, the size and form of a woman, pressing close beside me.

I was rocking Jonah in front of the fire. Clark had fallen asleep beside Sophie upstairs. The house was deeply quiet. There was no wind outside, no rustling leaves, no creaking trees. Even the cats were dozing. I had turned off all the lights and was singing softly to Jonah, holding him against my shoulder. He, too, had long since fallen asleep, but I was enjoying the warmth of him in my arms.

Jonah was a big, easy baby, a delight to cuddle and hold. I pressed my lips against his smooth, almost bald head, to savor the smell of him. That’s when I felt her beside me.

If the vision was brief, the emotional sensation of her presence was overpowering. She was there.

My first feeling was a mother’s protective terror. My arms tightened around my son. I wouldn’t let anything touch him, take him, harm him. I was ready in an instant to fight for him. But that instinctive fear of the unknown was replaced almost immediately by an overpowering sorrow. It welled up from within me like some great tidal surge—but I knew nearly at once that it wasn’t my own. It was her sorrow, that of the woman who was beside me.

In my heart I already knew who she was.

Years later I would befriend a psychic who explained that for the dead to materialize in our presence takes an extraordinary amount of effort. They don’t do it easily or lightly. They don’t do it to terrify us, either, even if the experience can be frightening. They come with urgent messages and desperate pleas.

I could feel the love of the woman beside me for the baby in my arms.

I recognized it. It was no different than my own, except that hers was shadowed by loss and longing.

She had been my son’s mother. How many years ago, I couldn’t say.

There’s no way to prove any of this, of course, but for me the knowledge of it was immediate and complete. She had been Jonah’s mother in another life. She had held him as I was holding him now. She, too, had felt rapturously in love with his sweet gentleness. But she had lost him. Suddenly. Terribly. Much too soon. Like the lovers separated from each other in my childhood television show. I could feel it in my heart. For lifetimes she had ached to hold him again.

I suppose, in those days, I could have ignored what I was experiencing. I could have turned on the lights, the television, the computer, and dismissed my vision as the result of an overactive imagination. Shrugged it off. Explained it away. That’s what most of us do, and what I had most likely done any number of times before. It’s a natural reaction, because we are frightened and do not want to be frightened.

But I recognized the clarity of her love and the depth of her sorrow. It pierced me like a needle going from one side of the cloth to the other.

The test before me was between love and fear. Maybe all of life is about that choice. Maybe that’s what everything depends upon, the courage to choose love over fear even in the face of the unknown.

“You can touch him,” I whispered out loud, somehow knowing she needed an invitation. “Kiss him. Hold him with me. Please.” It was what I would have wanted, were she the mother and I the shade.

Her presence enveloped us. I no longer saw her, but I could feel her as close as my own body. I could feel her joy at touching him again. She had lost him as a baby, hadn’t she?

Was I too trusting? Should I have been waving sage around the house or muttering protective mantras? Was I oblivious to the possibilities of evil? Those were the insidious, marginally more rational, questions hovering at the edge of my mind. But in the dark and the quiet of the moment I was able to dismiss them.

“Love him,” I said. “But watch over him, too. Help me take care of him always and keep him safe. Be his guardian angel, his fairy godmother. I don’t want to lose him like you did. Please.”

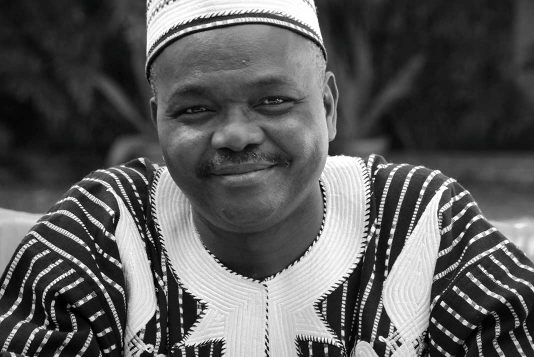

Years later, at a workshop with the Dagara elder Malidoma Somé, I would discover that I had intuited one of the most basic principles of ancestor practice during this encounter: I gave the spirit an assignment. I acknowledged her presence and I identified her, as best I could. But I didn’t stop there. I also gave her an opportunity to collaborate with me. I invited her to engage with me in my work and my life. Still, at the time I didn’t really understand that our relationships with the dead are, well, relationships. We feed each other, we bless each other, we have gifts to offer each other—if we can stay open to them.

By daylight the whole encounter seemed impossibly strange. I finally dismissed it as a product of the overwrought emotional state of young motherhood. I mentioned to Clark as casually as I could that I’d had the weirdest sensation in the dark. But I dismissed it with a shrug and a nervous laugh and didn’t elaborate. Finally, I forgot about it altogether, as the demands of mothering two young children filled my every moment. After all, every encounter with a three-year old and a baby—from snowflakes to ants to clover in the grass—is filled with supernatural wonder.

We explored the mountains together, following the ridge behind our house through the woods and wandering along streams. We turned fallen trees into dragons and befriended them, climbing onto their backs for wild imaginary rides. A great blue heron had spread its wings and lifted off above our house when we arrived in Woodstock that first fall, and it returned in the spring, like a pterodactyl having flown through vast stretches of time and space to land in our pond.

The Catskills may be very old mountains, but they are not true mountains in the geological sense. They were formed eons ago as rivers made their way to the sea, wearing away deep furrows in the land and creating a vast delta that age after age gradually deepened, measuring the depth of time in the height of the hills. Those ancient worlds were visible in the rocks themselves—in the striations of bluestone, vast compressions of sand and silt. Each layer held a million years of ocean life. In our backyard we would hunt for bits of stone embedded with the fossils of trilobites and brachiopods. I had grown up at the ocean hunting for shells, and now my children, here in the mountains, found the long-gone remains of sea creatures beneath their feet.

At the shore where the tides wash away the sands, it can be difficult to remember how deep the ocean really is, how deep the passage of time is, but here in the mountains we felt it all around us and beneath us. The vanished worlds of our most ancient ancestors.

Listening to the owls calling to each other in the night, I sometimes wondered how many spirits haunted these dark forests. When every rock is a tombstone, how far back do the ghosts really go?

That spring I took a train down with the kids to my brother’s house in Westchester. Not only did I have the baby to hold and my daughter’s hand to clutch, but my arms were filled with diaper bags and toys and books and juice cups. I explained to Sophie that she had to be very careful when we got off the train. “There’s a big gap between the train and the platform,” I told her. In the past I’d carried her over it, but I couldn’t now that I had the baby in my arms. “I’ll hold your hand, but you have to jump. Okay?”

“Okay,” she said solemnly, nodding her head.

The train pulled into the platform, and we all stood in front of the doors, waiting for them to slide open. I was watching Sophie’s feet. She was still so small. I didn’t want her to fall or trip. She looked up at me. “I’m ready to jump!” she said.

The train groaned and exhaled as it came to a full stop. The doors in front of us opened. Sophie easily leapt onto the platform. The gap was not nearly as vast as I had remembered. But in that instant of relief, I simultaneously experienced complete and total horror.

Jonah’s arm had been pressed against the door when it slid open and now it had been swallowed whole into the train. He screamed in agony. I didn’t dare pull him free, afraid his arm would come off.

“Help! Help! Help!” I shouted, terrified the train would start up again with my son’s arm stuck inside the door. I was clutching Sophie’s hand and holding my baby. All around us passengers were screaming. An older woman scooped my terrified daughter up in her arms.

“That baby’s lost his arm!” yelled a businessman.

“Where’s the conductor? Get the conductor!”

“Stop the train! Open the doors!”

“Call an ambulance!”

“I’m dialing 911!” someone yelled.

I was holding Jonah. But I knew he had lost his arm. He wasn’t going to have an arm. I was desperate, frantic, and everything seemed to be taking much too long.

Suddenly there were conductors and police running toward us. The commuters cleared a path for them. A police officer wrapped an arm around me. The conductors conferred, their faces grim and pale.

“They’ve decided to slide it open manually,” the police informed me. “It’s the only way.”

I was too distraught to speak. I had no idea what was best. Jonah was wailing, letting out huge gulping sobs of terror and pain.

Leaning on the door, with one of the conductors inside of the train and one on the platform, they slowly pulled the door from inside its sleeve. I braced myself for the horror of what I might see.

The door budged an inch, and then a little more. Sirens wailed in the parking lot—a fire truck and an ambulance. The conductors groaned as they slowly edged the door out.

“Mommy! Mommy!” cried Sophie. “Is our baby going to be okay?”

And then the door was completely open. The crowd was cheering before I dared to look. But there was Jonah, and there was his arm, still attached to him—unscratched, unbruised, unharmed.

“It’s a miracle!” whispered a man in awe right behind me. I could tell that he, too, had expected the worst.

The conductors helped me off the train. I could barely stand. Then the officer drove us to my brother’s.

I recounted the whole story again and again that night, first for my brother and his wife, and then on the phone with Clark. It wasn’t until much later, when we had settled into my bed in the quiet and Sophie had fallen asleep under one arm while Jonah nursed quietly on the other side of my body, that I remembered her—the ghost, the spectral presence, the dark mother to whom I had entrusted my son’s well-being.

“Some help you were,” I said. “I thought I told you to protect him.”

The house was dark and quiet, but a deeper silence seemed to open all around us. I felt an ocean of darkness swelling in every direction—one that was filled with beings, all listening, all waiting, mothers stretching back and back to the bottom of time.

A voice spoke, and I heard it as distinctly as if my own mother were speaking beside me. “Is there even a scratch on his arm?” she said.

Chills prickled over my whole body. I looked again at my son’s arm. Not a bruise. Not a scratch.

“Thank you,” I whispered into the darkness. “Thank you.”

This is wondrous. Thank you.

Powerful! And a reminder that love continues to find us from another place.