Relearn the alphabet,

Relearn the world, the world

understood anew only in doing

~Denise Levertov

Each time we speak, we give birth. Something of our soul goes forth into the world, embodied in air.

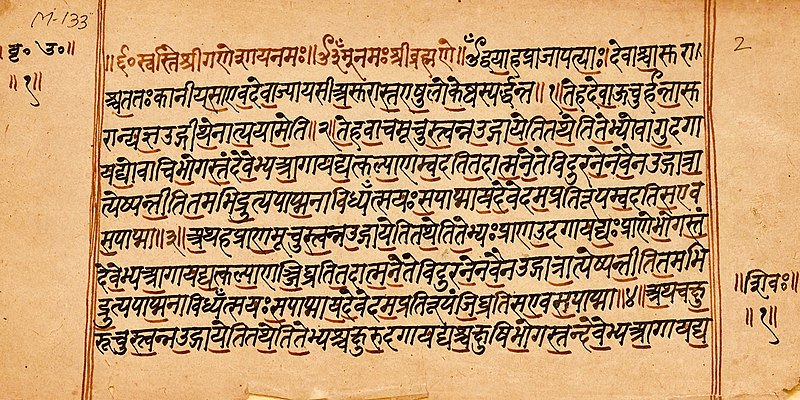

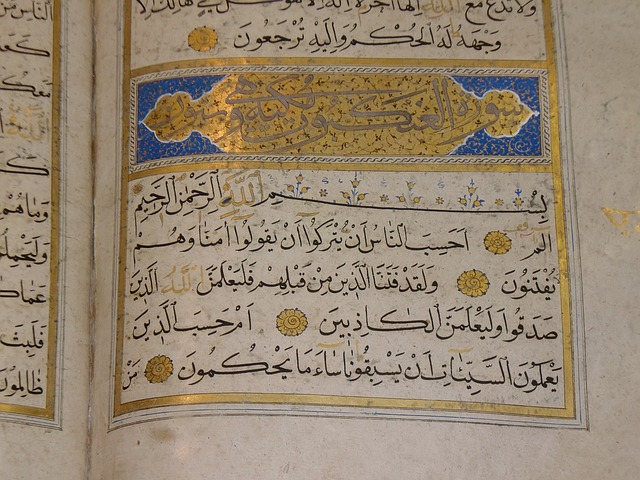

It is remarkable that this indispensable tool of the thinking soul, so vital to our adult sense of self-awareness and to our intellectual development, is given to us in utter unconsciousness. Speech comes to us from an unknown realm of wisdom, a realm that has traditionally been identified with the divine, and with the divine sacrifice that makes life on earth possible. The goddess Sarasvati appears in the Mahabharata “adorned with all the vowels and consonants.” Krishna is described as a manifestation of the divine Word; Christ, as the Word made flesh. Odin hangs himself on the world tree for nine days and nights in order to win the sacred runes, to imprint the godly gift of language into matter.

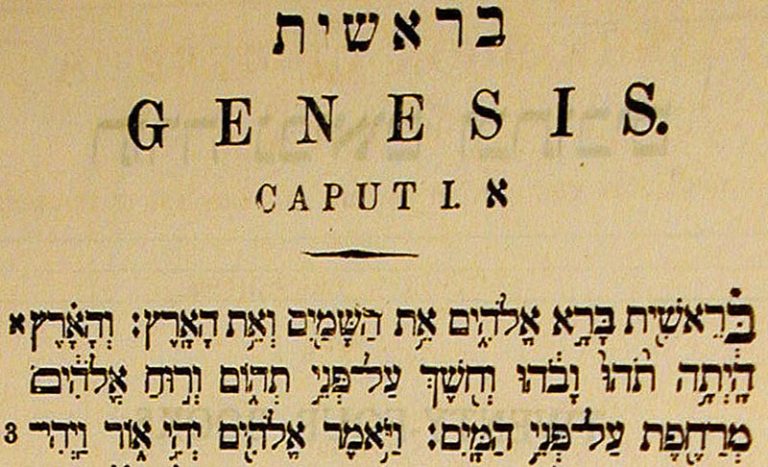

A Jewish legend tells of how the letters of the alphabet, already in existence before the world was made, each petitioned God to be chosen as the portal of creation. Only one was found worthy, Beth, which eternally says “Blessed be the Lord for ever and ever.” And so it is that the first word of the Torah is Bereshith, “In the beginning…”

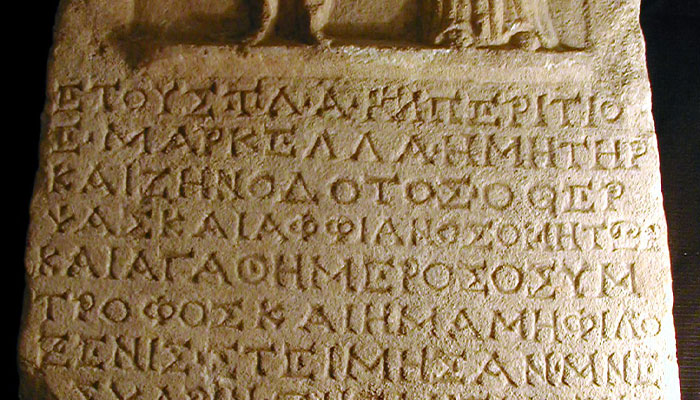

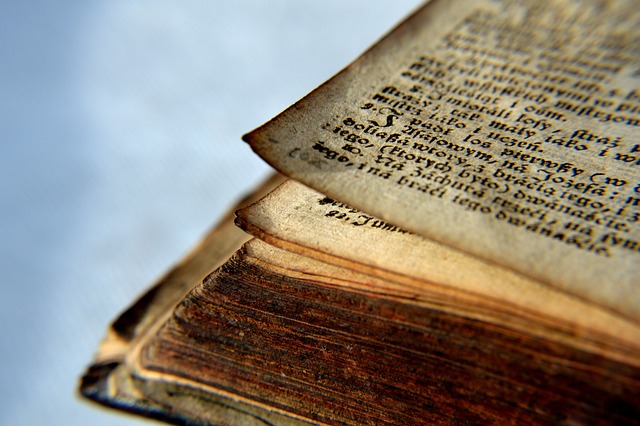

The alphabet itself, step-sister of speech, has naturally become a powerful symbol of the marvellously differentiated wholeness of the world. Before they became secular tools of commerce, politics and propaganda, the letters and the sounds they represent were seen as individual vessels of divine creative energy, each with its own attributes, identity and purpose. Though it has been called the most astonishing achievement of the human intellect in history, the invention of the alphabet has never been claimed by a mortal, but in every tradition ascribed to a god: Hermes, Brahma, Thoth.

The vowels and consonants, Sarasvati’s ornaments, have from ancient times been distinguished as forming two great divisions within this wholeness. The vowel sounds are most primal, being composed only of air from the lungs, given voice through the larynx, and resonating in an open, unobstructed vocal tract.

In the vowels our breath, which from moment to moment is our most vital and life-sustaining function, abandons its usual silent servitude and becomes radiant, penetrating sound. Like light passing through a prism, it reveals a previously imperceptible spectrum of color. The invisible, inwardly experiencing soul thus announces its presence through the medium of the body. It is no accident that when moved by strong feelings, our most instinctive interjections are strongly vocalic: the “Ah!” of admiration, the “Hey!” of surprise, the “Ooh…” of fearful suspense.

Vowels were not written in the earliest alphabets, a phenomenon usually explained by the fact that in the Semitic languages they represented, vowels were easily inferred by the surrounding consonants. Perhaps, too, in earlier times our ancestors still sensed the human soul speaking in the vowels, and did not care to fix it too firmly in the physical world through writing. Something of the heavenly origin of the soul still lingers in these singing sounds; in the Upanishads the vowels are equated with heaven.

The consonants, on the other hand, all obstruct the flow of the breath in some way. They are equated with earth, with the creation of the visible, material world. They contain and house the soul; Beth, the primal consonant of legend, means “house.” Each letter in the earliest alphabets began as a picture of a physical object and carried its name: in Phoenician kaph (hand), nun (fish), resh (head). The picture acted as a mnemonic for the initial sound of the word: K, N, R. This litany of names was a rooting in earth, in the bodily world. A language without consonants would have no form; however, a language without vowels would have no life. The vitality of the vowels and the shaping power of the consonants work together in rhythmic alternation, mutually interdependent.

The Greeks adopted the alphabet of the Phoenicians without understanding their language, and so the letter names became meaningless, their forms no longer pictures. It was a step towards abstraction, necessary for the birth of philosophy and science, but leading likewise to our modern alienation of body and soul. It is significant that the Greeks were also the first to adopt written letterforms for the vowels. As the outer world became abstract, the inner world began to lose the strength of intuition.

In poetry, an art which takes the whole human being, body and soul, as its instrument, we may find reintegration. Take two lines from Shakespeare: “I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought / And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste.” Speak the second line aloud, and notice how effectively the vowels, together with the semivowel W, carry a release of feeling. Imagine being unable to moan in pain or to exclaim in joy; the sounding breath brings healing and balance to the soul.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, meanwhile, floods us with consonants: “This darksome burn, horseback brown, its rollrock highway roaring down…” B, K, N, R, freed from their ancient associations, still carry a powerful picturing quality. They bring a visible world, with its surging river, into being. As an exercise, we can try to become aware again of their particular forming qualities in the words we use every day. How many B words evoke a protective covering, a “house”? Bubble, balloon, basket…

When we were first starting to babble, each sound was a revelation, a new creation for both body and soul. Can it become so again?

Originally published as “Embodied in Air” in Parabola, Fall 2005.

Well done, dear handler of the snakes of language. So well done.

Thank you!

Dear Lory,

Such an interseting essay on a topic close to my heart. Your writing is beautiful and is a real joy to read.

Thank you so much, Michael!

Oops, I hit send too soon!

I love the meditation on letters as connected to the body and to breath and then finding their harmonious fruition in poetry. Thank you so much for writing this fine essay. One interesting fact is that in Sanskrit the vowels come first, and found their written form prior to the consonants! I have just completed a manuscript of poems, with each poem based on a letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. One of the poems appeared here in “Braided Way,” recently!

Here it is: https://braidedway.org/%E0%A4%89%E0%A4%B6%E0%A4%B8%E0%A5%8D-usas-goddess-of-dawn/

Thank you, and let me know if you’d like to chat about sacred alphabets sometime!

Michael Sowder

What a fascinating project, I’d love to learn more. I did not know that about Sanskrit. It would be wonderful to chat, how would that work? You can always get in touch via my blog, and I’ll check out yours too.

That sounds great. I’ll be in touch via your blog! My blog has not been active for a while!

Thank you for this essay, Lory! Such a delightful guide to seeing more of the wonders of language. Now bringing more consciousness of speech and sounding, into this day.

Dear Susan, thanks for your note! Yes, language is truly an everyday wonder of which we often have little consciousness. I’m glad if this provided some inspiration to notice it more.