He floated in his currach, that oxhide covered wicker vessel, into the misty landscape of my childhood. I learn St. Brendan had crossed the Atlantic with little more than the faith that sustained his life as an early Irish monk. This type of spiritual practice known as peregrinatio was a common form of devotion among Christians at the time. It committed one to leave home on a journey without a planned destination. The pilgrim wandered in complete faith that Spirit was leading him or her toward an unknown but awesome destiny.

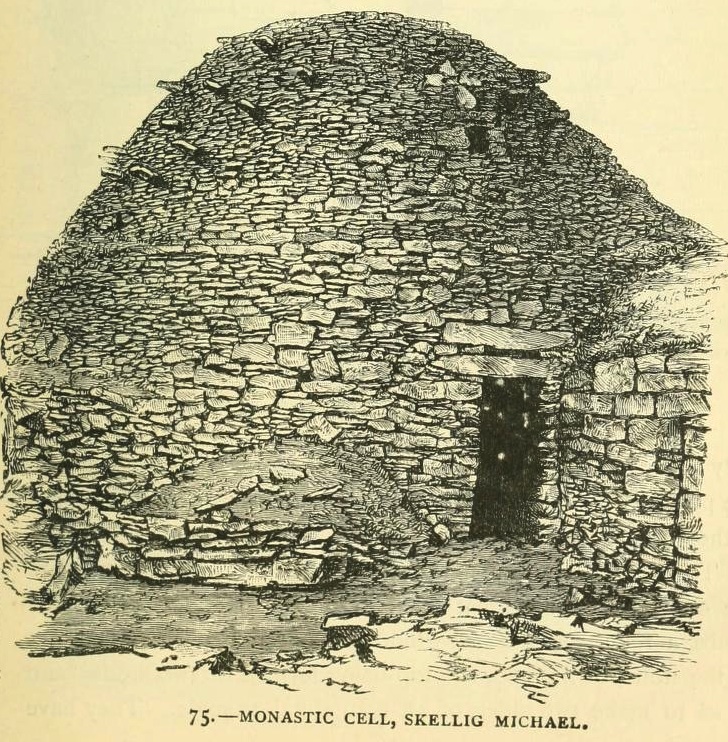

Years later my friend Mark visited Skellig Michael, an island off the southwestern shore of Ireland, famous for the wild winds slapping against its precipitous cliffs. What could inspire the hermit monks to build their beehive stone cells barely large enough for one person and then face an alien forbidding world where one lived at the mercy of the elements – storms and endless sea, cold and damp? Mark had an epiphany moment when fear gripped him on his own ascent of the peaks. Here he came face to face with the great Mystery of the unknown which he claims we try our best to keep at bay during a lifetime of safe routines and rituals.

I concluded these monks lived with a strong sense of identity and purpose connected to a place, a faith, and to each other. Like many I struggled to find my own connections to place, faith and community. I floated for years without a clear cultural or spiritual identity. Sometimes my trajectory was aimless, sometimes driven. I released many of my former identities: daughter, lover, Christian, teacher, American, before adopting friend, seeker, poet, contemplative, activist, global citizen.

Through all the labyrinthian twists and turns of my life Brendan never failed to appear. He once showed up on-board a ship carrying me from Hollyhead to Dublin when I was nineteen. I took comfort in the painting inside my cabin of this Celtic saint blessing the whale he named Jasconius. The blessing extended its mantle over me at a time when, living alone in a foreign land, I struggled to understand my first encounter with death. A fellow student had jumped off the roof of our college only a month earlier.

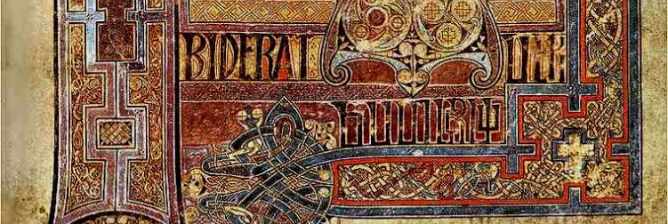

In my twenties, I found Brendan on the cover of a book on Celtic saints that fell off a library shelf to land at my feet. At one point, he even competed with St. Kevin for the most renowned exploits. Brendan visited the isle of talking birds, beached his boat on the back of a whale, and eventually came to rest in the land of the saints, his own version of paradise. Not to be outdone, Kevin held his hand out to shelter a distressed mother bird who laid her eggs in that warm embrace. Fearful of disturbing the nest, Kevin maintained this vigil, holding his precious cargo for weeks through rain and shine, until the baby birds hatched. These two legendary saints thrilled me as a child with their fantastical exploits. As an adult, I fell in love with the pagan aspects of Celtic spirituality: a deep connection to nature, the Divine Feminine, contemplation, and social justice.

The first year of the pandemic, I found myself wrestling like Jacob with an angel who called me to accountability. I woke in the middle of the night challenged by questions and the safe projections I had depended on for meaning most of my life. Was this really who I wanted to be when I grew up? And, yet, I was grown up and facing my waning years. We are all said to live with regret. It was true that I struggled with bouts of loneliness in my search for kinship. However, when I explored my life choices, often at odds with the popular culture, I found a sense of satisfaction. There was joy in my contemplative and creative practices and meaning in my commitment to social and eco-justice activism.

These values had landed me a home in the woods on a tiny lake in Michigan where I got to know a number of trees, plants and animal on a first name basis: oak, pine, hickory, mullein, chicory, nettles, possum, tree frog, and deer. I found my second calling to write and paint. In this place, my family of activist friends helped me create a healing ritual for our Day of the Dead ceremony honoring women and children who had been murdered in our community. Later we stood on street corners with our “Stop this next war,” and “Black Lives Matter” signs. One day I spoke out-loud a new manifesto, “My life is filled with riches.” Despite the challenges that come with the loss of a partner and that sense of deep connection, I finally realized that most of the time I am truly blessed with both gratitude and joy.”

During the second pandemic year, a friend’s email showed up suggesting I read The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin. Once again this favorite mariner-saint sailed into my life. Encouraged by Brendan’s presence, I decided to google my last name through an Irish ancestry site. In previous attempts, I discovered an ancestor who was shot by the English for stealing a loaf of bread during the Irish Potato Famine. This time I was to uncover much more.

Before my eyes, the page outlined a history that went back to the 12th Century when my apparent ancestors acted as liaisons between the village people and monks of the famous monasteries dotting the Irish countryside. They were the go-betweens exchanging food and medicines, as well as reading and catechism lessons for labor. I concluded these ancestors had a special role including both contemplative and activist traditions. Taking a deep breath, I relaxed. After all my years of wandering as a pilgrim who had left the familiar territory of her life behind, I now discovered the beautiful path Spirit had carved for me, a destiny I couldn’t have imagined. Here was my heart’s desire. Here was my tribe. I was home.