As I watch Jordan’s aid fall from the sky, over a Gaza of tattered tents and prolonged terror, I wonder how anyone can see help as evil? The act of delivery, the act of feeding the hungry and the sick and giving the wounded what they might need to heal. How can this be wrong? How can this be a threat? This witness of the west, they tell us we don’t see with our eyes. But I know what I see: doulas in the sky.

I remember how people have chosen to depict babies being born and brought to us in this way. Softly carried by birds or wind. Parachutes are hope, otherwise we are in freefall. We know how babies really come, but the desire for gentleness and heavenly favor remains on our hearts. I think of the babies who never got a drop of milk before meeting the one that carries us all home. I think, more than anything, of how a parachute of aid is the polar opposite of guns and bombs, no matter who tries to say otherwise.

On the same day of witness, I open a little black book. It is Lent. I have never sustained a Lenten practice, mostly because I never really tried or saw it as something that could bring sacredness into my life. I have had one foot out the door since I could read my religion. My parents weren’t committed enough for it to stick, either. Yet, my grandmother – a Transylvanian fortune teller and ancestor for about 25 years now – recently came shouting for me to follow the old way. The way of both, and. The way of the many. The way we can have many stories and spirits and saints, with a divine force that weaves them all together. She made a living cross of her body, bringing babies into a world torn apart by wars and walls, in fact. Her sons she named for saints and blessed them with folk balms, ancient flickerings of Cucuteni and Dacia – believers of other gods. She used only the word prayer for all her forms of magic.

With her sitting atop my spine, as many of our guides like to do, I read the story of Christ at the brink of his betrayal. I think of Gethsemane and Gaza, two millennia ago and now. I am less concerned with the difference between the angel that comforted Jesus in the garden and the parachutes that rained on the months’ long drought of humanity. Hope flies.

Every morning, after reading the Gospel, I draw tarot. This, my grandmother’s gift: both, and. Images of Torah glint from the cards. Images older, too, than an Abrahamic god. If done with intention, the Major and Minor Arcana do not whisper only of my path. The plight and prayers of Palestine and Israel are hidden in the folds of their robes.

If enough pressure is applied on either side of a clay pot, a crack will form. Sometimes I think all the world’s hurt, generations of trauma and displacement – true and porous stories – have made a crack in the Holy Land. Everyone there is afraid to fall through. Everyone watching is afraid they might, too.

I am okay with people thinking my spiritual practices are heathen, for I know that I come from a long line of people pickling and poulticing and braiding traditions to survive. My people built thousands of altars along the sides of winding roads, filling them with candles and saints, only to go back to their villages where they danced in bear skins. For whom, we all know but do not quite say. They still do. Every candle, every dance, repairs the cracks of the world.

They still do.

In the Carpathians, the nationless blanket of mountains from where much of my ancestry stems, there is a very old god. She’s almost been lost dozens of times. So many campaigns to blight her from the land. Yet, she remains. Her name changes, as does her face. She has belonged to Jews, Christians, pagans, and many others alike. Her name is Baba Yaga.

There is undue focus on the physical appearance of Baba Yaga. It goes beyond her crone body and face, to critique what we think she is up to in the dark woods. People mistake her for being only about death, missing the forest for the trees, for the death that she brings is only in the promise of life. We shun what we do not understand, and Baba Yaga is patient with us in her strange, chicken-footed house. I suppose she could fly herself anywhere, travel out of the woods that she both chooses and is exiled to. Yet, that is not her life-message.

She is a native plant.

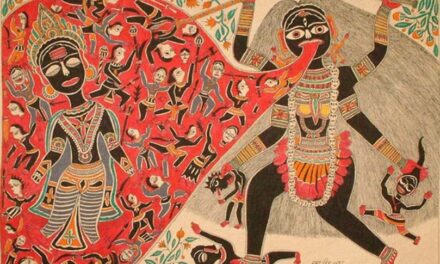

For justice, however, she has traveled. In a miraculous, physics-defying mortar and pestle, she does fly. And for those of us who know the conjuring qualities of her name, we can see her in the world. When parachutes fell from the sky, some might have seen manna, some Christ, some Baba Yaga. Blessings have infinite names.

Lent is as much Baba Yaga’s season as it is Christ’s, for compost and resurrection, winter becoming spring, death into life, sacrifice and suffering transmuted into an eternal hope, are their common tongue. Both of their stories teach us about being deeply misunderstood, and the repercussions of missing their message. Both are for peace, but not the kind that comes from laying down and waiting. Even seeds fight the dark earth to break free.

My Lenten book asks me to look for Jesus here, among the living, on the land. My ancestral knowing asks me to look for Baba Yaga in the sky. Doulas of a new way, a new world. Between earth and sky, darkness and light. Whose blessings are for those as forgotten and misunderstood as they. Look for them, for their parcels and parachutes, so that all who hunger might taste freedom.

” I think of Gethsemane and Gaza, two millennia ago and now.” Dear Isabel, You captured the

soul of Lent for me in your beautiful piece. Thank you for honoring all the babies, all the innocent

children being murdered in Gaza. Lent is truly both about the dark mother, Baba Yaga, and the

journey of Jesus – both promising life even when we can barely imagine any longer that resurrection

is possible. Continue uncovering the prophetic voices around us.

Thank you so much for this. Lent is such an important time and the way some churches avoid the topic of Palestine at this time is so disappointing. This was incredibly beautiful.