You should entreat trees and rocks to preach the dharma, and you should ask rice fields and gardens for the truth. Ask pillars for the dharma, and learn from hedges and walls. In earth, stones, sand, and pebbles, there is to be found the extremely inconceivable mind which moves the sincere heart. —Dogen Zenji

Dogen Zenji, the founder of the Soto school of Zen, lived in Japan over eight hundred years ago. As a young monk, he’d thought that the mundane aspects of life distracted from serious practice, but by the time he’d attracted his first students he’d realized his error.

As the abbot of a temple, Dogen wrote meticulous instructions for carrying out daily tasks, from cooking and cleaning to brushing one’s teeth. He didn’t want students to squander a single moment of the day. Mindfulness was not to be confined to a meditation hall.

Though Dogen’s practical instructions were intended for monastic communities, we can apply them outside the monastery confines and into the garden, where doubts sprout, weeds abound, and the mind blooms beyond all barriers.

“In performing your duties, maintain joyful mind, kind mind, and great mind,” wrote Dogen. Everything you do, everywhere you are, is a reflection of your own mind. So how does a tiresome chore become instead the activity of a buddha?

When I moved into a home with an old, overgrown Japanese garden, I could not have answered that question. My mind swirled with a combination of giddy naivete and petrifying doubt. I didn’t know anything about plants. I had no training, tools, guide, or supervision. Convinced that there was a right way to use a spade and a special time to plant or prune, I was pretty sure I’d do it all wrong. It was far safer to gaze at the place through my kitchen window or read one of the many gardening books I was busy collecting.

And yet, I could hardly wait to begin. Here was life right in front of me, not merely a clever scheme or distant dream. The only question was when I would get out of my head and into the dirt. That’s the question for all would-be gardeners, as it is for practitioners of the way, and the answer is the same. You just start.

As Dogen put it, “Use your own hands, your own eyes, and your own sincerity. Working with your sleeves rolled up is the activity of a way-seeking mind.”

Right in front of me was a place teeming with life and rampant with possibilities. For a gardener, what place or time isn’t full of possibilities? Despite my lack of qualifications, I trusted that my hands knew what to do and that luck would see me through. I started pulling weeds and graduated to raking leaves. From that point on, every day in the garden delivered a good day’s work.

The natural world fulfilled me as nothing I’d done while stuck at a desk. What made it so? If I only pay attention, a garden tells me what to do. No further knowing is needed. In fact, it probably gets in the way.

To my eyes, the more time I spent in the backyard, the more beautiful it became. Not because my skills improved, but because I no longer viewed the garden critically, as separate from me. Wisdom is closer than you think. As close as your hands, as intimate as your sight.

“Not dwelling in the realm of right and wrong, directly enter unsurpassable wisdom,” Dogen taught. “If you do not have this spirit, you will miss it even though you are facing it.”

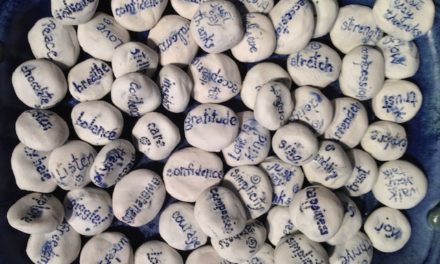

While gardening has not given me expertise, it has given me gratitude. I’m grateful to be following in the steps of my ancestors who reaped the fruits of the earth. “Is this not a great causal relationship?” Dogen asked, pointing out the karmic good fortune of being born human, living in harmony with all things, and being useful. This is joyful mind.

The second quality of mind described by Dogen is “kind mind,” which he likens to parental love, the selfless devotion to the life of one’s child. Yes, the work is never-ending. But I began to see the garden less as a wearisome duty and more as my own flesh and blood. Its growth depended solely on me, because who other than me was standing here?

Live among trees and grass, raising plants and flowers, and you won’t be nearly as obsessed with yourself, because you’ll never stop worrying about rain, sun, heat, cold, mildew, and moles: the near-constant threats to a garden. About this extreme kindness Dogen explains, “Only those who arouse this mind can know it, and only those who practice this mind can understand it.”

There’s another stage to raising children, and that is letting go. We don’t possess our children, nor do we control them. Our days with them are numbered, and they must be free to go their own way. To love unconditionally is to love without attachment or expectation. And so it is with a garden. Weeds sprout and flowers fall. A garden is, as all dharmas are, empty, impermanent, and ever-changing.

Over time, I came to see my role here not as the owner or landscaper, but as one in a long line of temporary caretakers. I wore a hat, pushed a broom, and used a rake. The garden had been here before me, and my intention was to see it go on without me. I took care of what needed doing, when it needed doing, and trusted the way. We are privileged to receive this great ancestral wisdom, and our work is an offering in return.

“The great master Shakyamuni Buddha gave the final twenty years of his life to protect us in this age of decline of learning,” said Dogen. “What was his intention? He offered his parental mind to us, without expecting any result or gain.”

By now, you might recognize that there are not three minds, but only one mind, Buddha mind: awareness freed from the dualistic judgment of right and wrong, self and other, inside and outside. Dogen called Buddha mind “great,” because it’s great like a mountain or an ocean, without partiality or exclusivity. It contains all things and allows all things. It is where we are and what we are, beyond our narrow, ego-minded views.

All that said, Dogen gives us precise instructions for acting in accord with great mind: “Do not be attracted by the sounds of spring or take pleasure in seeing spring garden colors. Allow the four seasons to advance in one viewing. In this way, you should study the meaning of great.”

To one who awaits the sudden burst of spring, this sounds like heresy, but it accords with reality. Dogen is telling us to be even-minded and not attach to appearances, which come and go. If we cling to anything, we suffer. There is no summer without winter, no flowers without falling petals.

A garden shows us the profound truth of life as it is: always new, always now, and always right in front of us. Look! Look! In every season, you’ll find a buddha here.

It could not be more perfect, as if such a thing were possible.

Karen’s essay is so effective the way it bridges Digen’s insights with her own work in the garden. And those photos are amazing. Dogen can sometimes be rather opaque, or maybe it’s just me. But this piece makes his wisdom more accessible.

Bows,

J

thank you. Beautiful reminder