The world is hurting. Fires. Floods. Disease. All the biblical elements are there, but I can’t assign them to God’s wrath. While grappling with apocalyptic scenes, it’s easy for worry to focus on personal health and that of our family and friends. It’s harder to remember that nature’s health is the first health on which we all rely. I take walks around my neighborhood and nearby parks and find nature as teacher, healer, and a conduit for communion with God. I see signs all around of elements that nourish both body and soul. Trees. Water. Animals. These connect me to the larger world and take me out of myself. And through the seasons, I am reminded of the circular patterns of growth, death and rebirth. Nature is the first foundation on which faith can be built. It is the tangible “one body” among the heavens, and it is at risk. What can be done to save it, and thus save ourselves?

“In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” As I move my fingertips from my forehead to my breastbone, then to my left and finally across my chest to complete the invisible cross, I wonder—how many times have I said these words? Thousands? Tens of thousands? This sign—holy and mysterious—is a gateway for me. My religion has given me that. A tool to reach God. As a child I thought of this act like picking up the receiver of a telephone and dialing a number. Only when I spoke these words and moved my right hand would I summon God to listen, to be there on the “other end.” The moment, however brief, became sacred. And only after my prayers, when I performed this symbolic act again, would we “disconnect,” would I let God go, and return to the secular world.

While this metaphor of the telephone has never left me, its simplicity belies the complex doubts I have about God and my religion. Since adolescence I have questioned ideas as fundamental as whether an omnipotent power exists and whether the practice of religion really does bring about a better world. Uncertainties swirl about me like an ill wind. What do I believe and why? It’s time for a reckoning.

When I contemplate the role of religion in my life, I mean Catholicism. I write here from my experience with this two-thousand-year-old tradition in the middle west of the United States, in the early twenty-first century, through a handful of mostly liberal parishes. One core belief has always defined my personal, central understanding of this religion: God is love. Anything that deviates from this is suspect.

Faith, on the other hand, is quite apart from religion. The latter should nurture and enrich the former and provide a place for it to be regularly strengthened. And yet as the world has seen, oftentimes religion does quite the opposite. Certainly, that has been true of Catholicism. Examples range from the recent horrors of pedophilia in the priesthood to the centuries-old persecution of Jews and Muslims during the Crusades. So it is a struggle. How does one maintain a relationship with the Church when it might thwart one’s faith in God or fellow humankind? In his later years, my father has taken to proclaiming regularly, “It’s the struggle that counts.” By this he means how we act in the world, how our beliefs are manifested in our actions. How hard it is on a daily basis to do what is right and good for yourself and those around you.

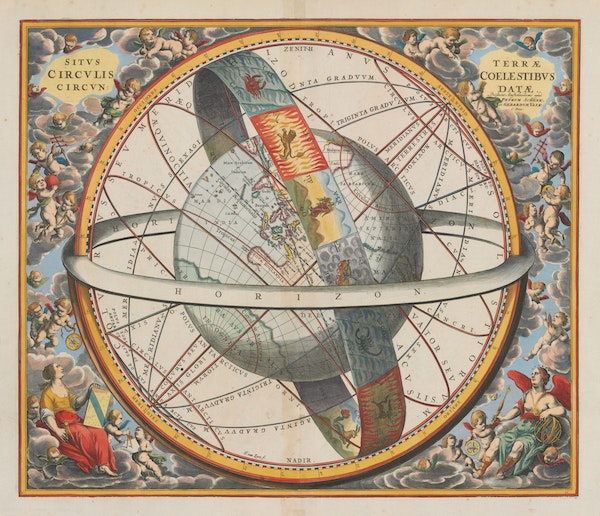

Andreas Cellarius, HÆMISPHÆRIUM STELLATUM AUSTRALE ÆQUALI SPHÆRARUM PROPORTIONE

Prayer is powerful. It rises forth from the belief that considering oneself or another person or a divine being can lead to miraculous outcomes. Prayer is a potent form of intention. What are our thoughts if not the beginning of everything humans have ever done and will ever do? I believe it to be a catalyst, perhaps the catalyst, for divine intervention. Prayer directs thought to first acknowledge our own human weaknesses and limitations and then recognize that we need one another or another force or both to intervene for our good. One another or another force. The two are not mutually exclusive and point to distinct forms of intercession. I believe great contributions can come through community. But I also believe in the power of the divine to assist with our deliverance from pain. This is quite different from collective action in that it acknowledges our human limitations for solving our problems. A spark, a gift from the divine, is sometimes necessary for us to transcend our terrestrial bounds. Regardless of how we are delivered, we cannot create change without first acknowledging its need. The acknowledgement is the start of transformation. This is prayer.

And like any repeated exercise, prayer can strengthen faith. It builds a muscle memory to lean on and launch into even greater strength. And in turn, faith can become a kind of bedrock. It’s the hard surface that can withstand the weight of questions and doubt. It’s an unwavering trust. During the early days of learning about the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church, many asked, “How do you remain a Catholic? Why continue to participate and support an organization amidst these atrocious acts, mishandled and hidden by leadership?” A good friend of mine and my mother’s believed that it was times like this when being Catholic truly meant something. Instead of living in an era when “you pretty much went by rote, and you didn’t have to work with your conscience, now you have a challenge, and I think it is exciting to watch where the Church is going.” To me this meant that one had to acknowledge that every “body” can be diseased. For those who stay in the Church, this can be an assertion that the sickness can’t be allowed to grow. If faith means anything, it should be the belief that a relationship can be healed in the midst of hardship.

Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Sadness begins the Catholic Our Father, since the implication is that we are a long way from the kingdom. But this is also where hope enters, and hope, not sadness, should open any prayer. As I type those words, I feel a sense of anticipation course through my body like water and blood. Yes, hope for “thy kingdom” can be possible if we attempt God’s will. But how can we know that will? Perhaps the Golden Rule comes closest. If we attempt to do unto others as we would have them do unto us, we are on the right road, which is just where the next line of this well-worn prayer leads. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us. The plainness of these words always causes me to pause to consider their brilliance. Here is a recipe for human peace.

At only fifty-five words, the Our Father or Lord’s Prayer is the Gettysburg Address of Christian prayers. It’s a poem given to us by what Christians believe to be God’s only child. The Catechism of the Catholic Church has called it the “perfect prayer…truly the summary of the whole gospel.” But for a long time, it was a little like foreign territory for me. For many years I could barely repeat the entire prayer. When I was in Church saying it, I would be fine. But when I tried to say it alone by myself, I often got to a certain point and then wondered, is that right? It didn’t sound right. There had to be a line or two I was missing. It always seemed too short, and I would be thrown off by its movement from the general to the specific and then back again. For example, when the prayer ends at Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, I’m at a loss. Whereas the prior lines about daily bread and forgiveness have specificity, this one is riddled with questions. What temptations? What evil? Sure, it’s easy to think of the big ones, the Ten Commandment type—thou shall not kill, commit adultery, steal, etc. But there are so many more. How will I know what to avoid?

My parents grew up with an entirely different approach to prayer, and my mom couldn’t believe I didn’t know the Our Father by heart. But for me to pray by rote as a private prayer is much harder than just talking to God, which is how I learned how to pray. In the middle of my life I have come back to the Lord’s Prayer. Committing the clarity of its words to memory has become important to my peace of mind. If I repeat the poem enough, perhaps its words, like holy oil on my skin, will enter into me in way that helps me to bear them out.

If prayer initiates a conversation with the divine, then what? How do we manifest the prayers we proclaim? Volunteerism is one answer. It gives evidence to the muscle and bedrock. For a long time my brother Paul worked for a program feeding homeless men, which he found through a parish in downtown Minneapolis. He would participate in cooking a vast quantity of hotdish—Minnesota’s signature goulash of ground beef, pasta, onions and other vegetables—in an industrial kitchen and then serve the men in the temporary shelter where they ate and slept. From time to time I would help him. As servers, we would ladle the food into bowls and place two or three cookies on top. The men filed past our wooden window to collect the food, and then found a spot along one of the many tables. Under fluorescent lamps, the smell of the beef and onions mixed with a sweet scent of chlorine. As long as the food lasted, the men came back for seconds. Perhaps a few tucked a cookie into their coats, to ease their hunger later. Many would be back the next day. From assisting at soup kitchens like this or helping children learn to read, to serving at precincts during elections or pitching in to build a new home—people can manifest love in their communities.

A prayer. A poem. Words matter. But most especially when they inform our actions.

Our Father who art in heaven. What is God? Where is God? And perhaps most importantly, why is God? Why does God exist? Catholics acknowledge that God is unknowable, which makes sense to me, and supports my belief that my God is not the only God. Others have their own names, and some believe in multiple authorities. That being said, within the Catholic Church, God is personified as male. Like many women in my life, I am exasperated by this contradiction. Christians believe we are created in God’s image, not the other way around. At the very least God should encompass maleness and femaleness? But why must God have any gender at all? The need for God to be male is mired in the hierarchical politics and structures of mankind. It is at this very first question—the what of God—that we, the religious can begin to go astray. If we limit God to that which is familiar, we lose the essence of God. If we believe God is a creator and a supernatural force, then the very definition of God should include mystery and fall quite outside the realm of gender. Only then can humanness be put in its proper place, a part of all of creation and not at the center of it.

There is a picture on a website of the Franciscan Poor Clares of Rochester, Minnesota. The picture is of a circle of empty chairs made of simple wood with beige cushions, behind them a fireplace, brick walls and brown paneling. This image conveys a familiar, spare but cozy space I remember well. As a teenager and young adult, I went on retreats and found myself in similar rooms, among other young women (and men) led by a nun, priest or layperson. Stillness would fall over all of us as we gathered to pray, to be anointed in both word and holy water. In the brief hour of gathering, I often experienced a sense of connection, feeling a part of a circle of relationship that extended outward to others—sisters, brothers, strangers. The expansion continued, to every living thing; nothing was left behind. Always upon leaving this sanctuary, I carried a certain level of peace back into my life. It was as if through this fellowship I found God’s loving presence and an internal flame had been refueled.

Where is God? In the context of a heaven, this question seems to me silly and inconsequential. What is heaven anyway? A cloud? A sanctuary adorned in gold and stained glass, where a choir of angels sing? Is God in some anteroom, off alone? A heavenly being or two approaching from time to time to ask for judgement on the recently deceased? So much anthropomorphizing. What good does that vision do for the world? But if I look at “where” as an abstraction, then it takes on significance. If God is love, then isn’t God everywhere? If God is in our rituals when we reach for the inexpressible, the mystical, then we can summon this supreme force at any time we are in great need or experience great human loneliness. It is here we can start to sense the divine, whether in personal prayer or collective worship. And as Christians, we are taught to believe that each person is created in the image of God. If we accept this teaching, then every one of us—even those who are evil and harm others—holds God within them. The connection of every living thing is the manifestation of God. We can use it wisely or for ill. We can create abundance or squander our gifts.

In the quiet dark of my bedroom, I once was a young woman who was very much afraid. This time the fear was not about death, but the common experience of a bad relationship. I knew the man I was involved with was not someone who cared about me, and still I could not leave him. I was desperate, and so, with hands clasped above my blankets, tears streaming down my cheeks, dampening my pillow, I stared at the wall and whispered over and over and over again, “God help me.” It was not a conversation, not the Lord’s Prayer. Instead a plea for mercy. Three words intoned into the darkness, seeking a receiver. Several days later, this man revealed himself to me. He knew I wanted to end our relationship, so he asked a friend of mine out for coffee, later admitting he would have eventually taken things further had she agreed to this first date. He had finally crossed a line I could see. It was crushing and yet transformational. I left him and began to consider what I really deserved. Did God intercede to show the man for who he really was? To unblind my eyes to what was always there in front of me? Or was it just a coincidence of timing, me at the end of my proverbial rope finally letting go? Maybe a bit of both. But I believe God heard me and provided a landing place.

Abundance. It is everywhere about us, there to be appreciated. Once during an autumn hike through a national park, I came to an awareness about life and death. It had rained the night before, and I drank in the cool air, smelling of the moist soil. I made my way through the gray birch and pitch pine, and I considered the trees. They needed very little. Just dirt, carbon dioxide, some sun and rain. And when they died, they became life for others. Hearing the sound of my boots on the granite, a truth surfaced. All life is connected and circular. These trees and I had grown from the same terrestrial body, the same supernatural realm. Nature provided this stillness, this space for consideration. This opportunity for grace. Like prayer, nature provides an opening, a chance to realize there is something beyond this world. If nature is in danger, we are in danger. If there are answers to this threat, they reside within our beliefs.

Thy kingdom come. Regardless of what words are used, the most important part of prayer is the act of pure humility, when we acknowledge how little we have in our control and how much we depend on others. Religion is the reminder that we cannot be in this life alone. It gives us community. It gives us prayers and practices. It gives us role models. Role models of both good and evil. In the end a religion is lived by humans as flawed and beautiful as our nature allows. Regardless of what we call God or how little we know of this force, I believe its spirit enters into the world and brings with it forgiveness—of our own sin and those who have sinned against us. And religion can be a doorway.

Divine intervention exists. It exists in the miracle of a flower or a bird. It exists in humans meeting each other in their needs and providing food and comfort. It exists in community, where two or more are gathered, their energy forming thoughts that lead to action, to transformation. It exists in the quiet spaces where we might face our fears. As many doubts as I have, I am sure of this. This force is as real as the movement of my right hand to my forehead and across my chest. And the call begins with prayer.