I was lying , not quite awake, in the west room when the angel came.

“Look out the window,” he said in a clear voice.

Having been raised a Methodist I knew that John Wesley looked out his window and saw the Godhead.

So, when the angel asked me to look out, I did, no questions asked.

“You will see the origins of the human race,” he said. “You will see your ancestors, back to the first generation.”

Looking out the window, I took in sky, White clouds, the mountains, magenta at dawn. But that was all. Nothing more. And then it started.

They held back at first . Only a disturbance in the air, a mere shimmering.

Then one firm foot, five toes set resolutely down, broke through the veil between our worlds. And hands, and faces, then whole bodies came to light.

Mother and Father appeared, younger than I remember, and stretched out their hands in greeting.

Elevated, standing in mid-air as solid as on earth. Naked. Expressing their God-nature more than ever they had in life. They entered the room calling my name. It was an invitation to look. “Do not be ashamed,” they said. They were as God had made them, as they were imagined in the Sacred Mind before their birth. They existed, in this moment, true and clear.

Injustice and suspicion, those wedges that kept us apart in real life, slid silently away, easy as raindrops falling from leaves.

I peered beyond them at the dawn mountains, now rust and green under a pale sky hung with fat clouds. My grandparents, all four, shoulder to shoulder, came to rest at my windowsill. There they were, James Lacey and Beuna Crawford, bringing with them the sweet air of a Texas orange grove. And on their left, Sol and Estelle, trailing a bit of New York hustle. Brundahl the hitman stands unredeemed alone. (In present tense to show it’s now.)

Behind them, great-grandparents, Eight, near the honey locust. I see hardworking Ada Ward to one side and Sali Mendelsohn, an Aussie go-getter on the other. They glance approvingly at one another.

Great-great. Sixteen, hovering over the garage roof. That’s Menthein Mendelsohn over there.

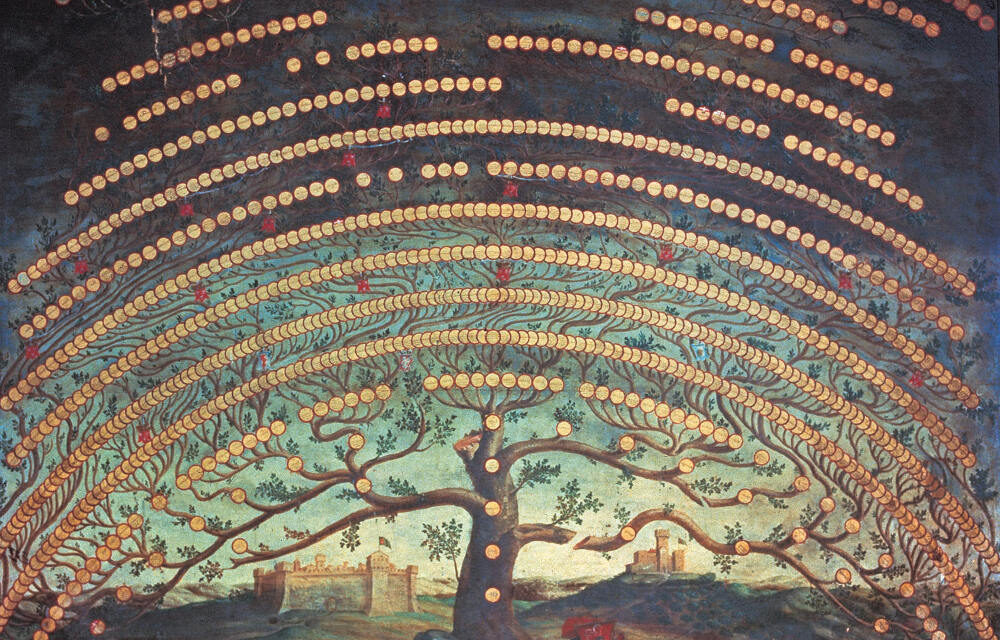

Generations back, back, and farther back. Past the telephone wires, the landmark pine. The school, the reservoir, fields, roads, the valley falling away below them and rising again in the distance. Generations reaching away in time and space. A horizon line disappearing over Mt. Evans.

I sit up, pull the covers over my shoulders and stare, blink twice, and stare again. Try to reason why they’re here.

Give up. Open my arms in awe and tenderness to greet the magical procession.

But wait! In the next moment, the voice of the angel deepens. A sound of dark branches lashing in rain. A shadow obscures the line of forbears.

“I have a message for you. You must listen with a clear heart and honor the truth I bring.”

How could I not? I wonder.

“How does it happen you were born?” the angel asks. “How does it happen YOU were born?

It was only because, nine months before your birth, your parents happened to have intercourse at the exact moment they did. If it had been a day earlier or later, you, as you are, would simply not exist.”

“Your grandparents,” he continued, “came together in turn at the necessary moment for your parents’ birth.” There was a chain, unbroken for generations, leading to — what?

To the event of the birth of one seemingly insignificant person: You.

One break in the line, one headache three hundred years ago, one sprained back a millennium past, or indigestion, or a night too cold or hot to kindle desire would have nixed the whole scheme.

I thought of my ancestors gently touching under animal skins, or silk and lace, pulling one another into an embrace on the banks of the Volga, Thames, or Rio Grande. One missed step in this procession of begetting would have left me… Nought, zero, zilch, nada.

From my view in this West room, the ancestors, Dali-esque, could be seen from above and below, all at once. Bare feet rested on the transparent platform of air, a horizontal column connecting me with the past.

No wise man regarding the infant Christ, no shaman returning from the Other World, could have felt more awe and wonder, or so I believed. Surely, some unfortunate, smelling the gun pressed to his head by his own hand, or perched teetering on the orange rail of the Golden Gate, could be saved by this message. How foolish to waste a life eons in preparation.

“How could I dishonor what I’ve seen?” I ask, “There’s no chance I’d take this lightly.”

“There is one way,” he answered. “That is to forget this vision.”

Yes. Of course. I knew just the way. “To be a mouse?” I wonder. I see her scurrying through tall grass, never seeing clouds, reduced to stashing seeds in earth. Clawing, tugging, scratching. Never knowing any world above the tops of vetch or vine, forgetting even to glance ahead. For all those plants read: the rent, the car, the clock, the grind.

“But I like mouse people,” I say in defense of Phil who runs the corner filling station and tends my carburetor with great care. “He is a good person.”

“That’s not the point,” says my visitor.

“Oh, what is, then?”

“Only this: to tend your vision with utmost care. To tend your vision.”

I wondered if Phil the grease monkey was visited with visions of eternal carburetion. And I knew I was doing just the thing the messenger had warned against–boxing, framing, and whittling down my view of heaven to a size capable of being carried by a mouse girl. I’d like to say that Right Resolve, all caps, reached out just then and took me by the heart, and left me clean and shriven— but that was later.

What happened at that moment was Granny–Beuna– my mother’s mother, covered my face with her hand and stroked from top to chin. “Cachula! Cachula!” she sang. I knew what she was doing. It was a spell to keep the Evil Eye away. She’d learned it from the Mexican women in our border town. It was a blessing, too. A gift.

I knew it was time for the ancestors to leave when they began to sing a benediction—a prayer to send their blessings to posterity, Leaving us to tend their vision with the care reserved for the Holy Sacrament it was.

Sylvia, this is brilliant. I did not want it to end.