Jeremiah opened his eyes. The first words to pop into his mind were ‘cozy eclectic,’ though how he knew these words, he had no clue. The office—and it did look like an office—felt homey with its deep green, patterned wallpaper, ample bookshelves, and large, mahogany desk against the side wall. There were shelves holding bits and bobs from across time, from arrowheads to AR headsets, though, again, how Jeremiah knew these words, he had no idea.

He looked down to find that he sat on a chaise lounge with smoothly carved wood to match the desk. It had a deep red velvet lining which felt calming in contrast to his eternally scratchy tunic. He was about to stand up and explore when, suddenly, a voice nearby made him jump.

“Goodness me, it’s the weeping prophet himself.”

Jeremiah looked around, his eyes finally landing on a man sitting across from him. How had Jeremiah missed him? The man smiled pleasantly, making a note on the clipboard resting on his knee. When he looked back up, his face looked innocent, with round, cherub features and brass spectacles beneath tufts of sand-blonde hair. He wore a beige waistcoat, a muted plaid bow tie, and brown leather shoes. He looked as though he’d been designed as part of the room. “I don’t think you know how eager I’ve been to get you on my couch,” the man said. “I’ve been watching you with particular interest, and I must say, you fascinate me nearly as much as Ezekiel! Honestly, though, who could compete with the whole cooking-food-over-human-dung spectacle? Much to explore there. Much to explore. That’s not to say you are dis-interesting, of course! The yoke on the neck? Masterstroke. Brilliant.”

As Jeremiah listened, he noticed that the man spoke in a tongue he didn’t recognize, yet somehow, he understood every word. After a moment, he noticed that the man had paused, waiting for Jeremiah to respond. “Um, sorry,” Jeremiah said. “What is this? Who are you?”

The man smiled. “And there it is, right on schedule. We know what this means, of course. Our time begins… now.” Reaching over to a side table, the man tapped a button atop a small clock, which began ticking down. “Right,” he said. “Let us begin our initial assessment, shall we? I’d say your published works are a good place to start.”

Jeremiah only stared. “Listen,” he said, “I have no idea what you’re talking about. I’ll tell you whatever you want, but can you please at least tell just me where I am?”

“Oh, of course,” the man nodded. “You are, at this moment, in my office.”

Jeremiah added ‘office’ to the list of words he didn’t know but seemed to know anyway.

“But where is your office?”

“Ah, slightly more difficult question.” The man thrummed his fingers on the clipboard. “Truth be told, I’d love nothing more than to tell you, but I strongly suspect the language I’d need might well result in the… how do I put this delicately? The implosion of your consciousness.”

“Implosion of… what?” Jeremiah asked. He understood the words, but they made no sense. He was beginning to feel slightly overwhelmed.

“Not to worry,” the man said. “It won’t matter soon anyway. Still, I do need to insist that we begin. The clock is ticking, after all.”

Jeremiah finally glanced at the clock. “What’s it counting to?” he asked. “Is it counting down to something?”

The man laughed. “‘Counting down.’ Very good. Time, I’m afraid, is an earth-based construct. Here, there is but an eternal now.”

“But…” Jeremiah nodded toward the clock, “it’s ticking.”

The man only shrugged. “Such is the nature of paradox. Now, as I said, I would very much like to talk to you about your published works on Earth.”

Jeremiah began to say something but suddenly stopped. “I’m sorry, did you just say, ‘on Earth?’ Are you implying we’re… what, that we’re not on Earth right now?”

“Oh, heavens no.”

“What do you mean ‘heavens no?’ Am I dead? Is this Sheol?” Panic began to set in as comprehension dawned. “Are you an angel?”

‘Angel’ was a word Jeremiah would’ve known regardless, but he’d always heard of them as fearsome things with manifold eyes and countless wings. They’d show up out of nowhere and praising the Almighty and scaring the bejeezus out of people. They looked nothing like the genteel man sitting across from him.

The man-who-might-have-been-an-angel chuckled. “‘Dead.’ ‘Angel.’ Funny, the human obsession with labels. Always trying to get drunk on the word ‘wine.’ That will come, I suppose. For now, however, I really must insist we press on. I thought we might just jump in, but I can see that a brief refresher may be in order.”

“Refresher?”

“Brace yourself.”

The might-be-angel raised a hand and pressed his middle finger to his thumb. Jeremiah was about to ask what he was doing when the angel snapped and a dam broke in Jeremiah’s mind. He found himself drowning in images. He saw his father in long, priestly robes, meeting with decorated kings and pompous dignitaries. He saw himself fighting with his parents over faith and politics, his mother trying to keep them quiet so neighbors wouldn’t hear. He saw his first conflict outside the temple, calling for reform and preaching against the corruption of the wealthy and powerful. He remembered the yoke rubbing sores into his neck as he tried in vain to make a point to these stiff-necked people, hell-bent as they were on self-destruction.

Jeremiah gasped and jumped to his feet, clutching his head. “What the hell was that?”

He remembered Egypt. The mob. The stones. The end. A lifetime in the blink of an eye.

“So sorry,” the angel said. “It can be a bit disturbing.”

“A bit disturbing?” Jeremiah cried, blinking away the afterimages of his life.

“Oh dear,” the angel said. “You’re upset. Here, have a cup of tea. Does wonders for the nerves.”

Jeremiah collapsed back onto the chaise, surprised to find himself holding a porcelain cup of steaming English tea. “How—”

“As I was saying,” the angel pressed on, “now that you’re up to speed, I do believe we should begin with a review of your greatest hits, so to speak.”

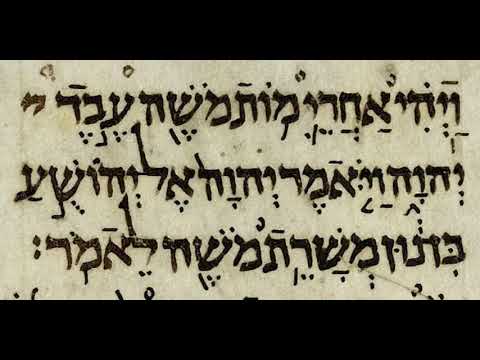

Again, the angel put his thumb to his middle finger. Jeremiah dropped his tea, bracing for another snap—porcelain shattering on the hardwood floor. This time, however, the snap only produced a scroll covered in Hebrew lettering. “Where were we now?” the angel asked, scanning down the lines of text. “Ah yes. Good a place as any.”

The prophet let down his guard, looking cautiously at the scroll which had appeared on the angel’s knee. “Wait,” he said. “Are those my words? Where did you get these?”

He wanted a closer look, but the angel waved him off. “All part of the job,” the angel said. “Now, here’s where I’d like to start. I’m noticing that while you showed significant progress in the realms of courage and integrity, much remains in the rubric of grace and gentleness.”

“Grace and—”

“Yes, not to be rude, but you were a bit of a… how shall we say? A fussbudget. Not to fear, however! All part of the plan. I should imagine a few hundred more turns would move us in the direction of—”

“Okay, okay, hold on a minute,” Jeremiah demanded. “Time out. I don’t know what all this is, and you don’t have to tell me, but I can’t stay here. I’ve got work to do.”

“Yes, that’s what—”

“No, you don’t get it,” Jeremiah went on. “Judea is in shambles. Greedy, corrupt opportunists hold the highest seats of power. The shepherds of the people are corrupt and blind!”

“Yes,” the angel agreed. “That does always seem to be the case, doesn’t it? Even so, I can assure you, all is well, all is well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

“No, you don’t understand—”

“Oh, but I do,” the angel said. “You see, I’ve seen it all, from alpha to omega and back again. I see it all now, even as we speak. An eternal now, as I said before. I am here to help you, you see. You needn’t worry about all that now. All you need to do is take a seat, lend an ear, and enjoy your tea.”

“But I don’t—” Jeremiah looked down and found that the teacup had returned to his hand, un-spilled and un-broken.

“Now,” the angel said, consulting the scroll again, “regarding your maudlin flare. Let us begin with this bit, shall we? ‘O Lord, thou newest: remember me, and visit me, and revenge me of my persecutors; take me not away in thy longsuffering: know that for thy sake I have suffered rebuke.’ I wonder if you would mind speaking more to this?”

Jeremiah stared. “Is this judgment? Am I being judged right now?”

“Oh no, merely assessed.”

Jeremiah continued staring, and the angel recognized his hesitation. “I assure you,” the angel said, “the only way out of this is through. Now, the ‘persecutors?’”

Jeremiah weighed his options, which felt stiflingly limited. In the end, he decided the best thing to do was to go with it. Maybe he would wake up. Maybe it was all a bizarre dream. He’d had stranger. “Sure,” he said. “Okay. Fine. Of course I had persecutors. You can’t exactly be a prophet and not make enemies.”

“And who were these ‘enemies?’”

“Well, everyone.”

The angel clicked his pen. “Let us try to be more specific.”

“Fine,” Jeremiah counted them off. “There were the priests, comfortable in their complacency, oblivious to what’s going on right under their noses. There were the politicians, getting fat by robbing the people. Then there were the idolators, worshipping lifeless stone and wood and lifeless tradition. There was everyone who whored themselves out like prostitutes to foreign gods, forsaking—”

“Sex workers,” the angel corrected gently.

Jeremiah stopped. “What?”

“Sex. Workers,” the angel repeated himself, more slowly this time. “That is the preferred vernacular, though I daresay that won’t come around for a few centuries yet. Still, more respectful that way.”

“Respectful?” Jeremiah repeated. “They’re prostitutes.”

The angel smiled. “You know it’s funny,” he observed, “that a person of your persuasion, who advocates for justice his entire life, would be so blind to the burdens of those struggling beneath the weight of that very injustice he seeks to uproot. Your belief in caring for others only seems to go as far as your social biases. Consider it. You would take a young woman who has fallen through the socio-economic cracks of patriarchal society, and you would shame her for doing what she had to do to survive? A tad hypocritical, wouldn’t you say?”

Jeremiah was unsure how to take this man seriously.

“Not to worry,” the angel said. “When we know better, we do better! Carry on.”

“With?”

“The idolaters and whatnot.”

“Oh, sure,” Jeremiah said. “Well, as I was saying, you can’t just do the kind of work I did and not expect to make enemies. Corrupt priests and rulers were leading our people astray, rotting the integrity of our nation from the inside out until we could act with neither justice nor wisdom. In their ignorance, they would bow to lifeless stones and images carved from wood, forsaking the Living God. They—”

The angel made a face and Jeremiah stopped again, unused to anyone interrupting so often. “What’s that? What are you doing?”

“Oh, it’s nothing. Please continue.”

“No, what’s with that face? What’d I say? I didn’t say anything about prost—er, sex workers again, did I?”

“Oh no, it’s just—” the angel started. “It’s the idolatry bit.”

“The idolatry bit?”

“Yes. I mean, you go on about the lifeless wood and stone over and over again in your writings, and one can’t help but wonder… surely you see that it’s not about the wood and stone, yes?”

“No.” Jeremiah understood this man less and less.

“Well,” the angel continued, “I simply wonder if we might consider it from their point of view for a moment. To one who considers an idol sacred, surely it is not about the idol itself, but what the idol means, yes? An idol points beyond itself, as every symbol does. For some, it might stand for family tradition, common stories, hope, meaning, etc. Some are able to find these things in your unseen god, and that is just magnificent for them, really, but can you not understand that others may not be so inclined? What of those whose own tradition has given them moral direction and purpose for generations? Or those who have been cast out or made to feel ashamed in the name of your god? Like the sex workers you are so fond of belittling. Can you really blame some for seeking their path elsewhere?”

“Sure I can,” Jeremiah said. “Our God is a jealous God.”

“Is he? Or are you an insecure man?”

Jeremiah felt a wave of indignation. “All right, what is this? I’m a prophet. You know that, right? I was chosen from childhood to be a mouthpiece for the Almighty. God himself has chosen me and burdened me with the reform of the nation, and you’re going to sit there and presume to tell me that I might just entertain some light idolatry? That it’s ‘not that bad?’ I thought you were an angel! Whose side are you on?”

“Oh goodness,” the angel said. “I see I’ve touched a nerve. Perhaps two points of clarification are in order. First off, I would remind you that ‘angel’ is your word, not mine. Secondly, I am on the side which is beyond sides, and I am only trying to help.”

“By insulting me?”

“Did I insult you? Dear me, I’m so sorry. I merely intended to speak the truth.”

“And what truth is that?”

“Simply this,” the angel said. “In reviewing your work, I have noted a persistent pattern of dividing the world into two. Everywhere you look, there is an us and a them. A hero and a villain. None in between. Even here, when I dared offer feedback, I became an immediate enemy, you see? What you haven’t been able to recognize, I’m afraid, is that truth very often transcends such dualities. ‘Prostitutes’ can be just. ‘Idolaters’ can be wise. ‘Angels’ can be unorthodox, and ‘prophets’ can be fusspots.”

“What’s a—”

“I am merely inviting you to imagine what might’ve happened with your work on Earth had you been less concerned with disapproval and division and more concerned with curiosity and grace. That’s all.”

Jeremiah scoffed. “I imagine I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere. No one would’ve listened.”

“Oh?” the angel said. “And as it was, people were tripping over themselves to receive your rebuke? Tell me this. Did your strategy of shaming Judea into submission ever work? I mean, truly, did any ever crumble in contrition at being called a ‘fornicator’ or ‘idolater?’”

Jeremiah shifted uncomfortably. “Not exactly, no.”

“And how did things work out for you?”

“A lot of yelling, mostly.”

“And ultimately?”

“I… well…” Jeremiah mumbled something inaudible.

“Sorry, what was that?”

Jeremiah mumbled again.

“Once more?”

“I was stoned to death by an angry mob, okay?”

The angel rested his case.

Jeremiah sunk back onto the chaise. Defeated, he took a sip of tea and found, to his great annoyance, that the angel was right. It helped.

“Were you always so tense?” the angel asked. “I see this in your writings. Always so serious. Never any joy or ease.”

“Ease?” Jeremiah repeated as though the word offended him. “You should’ve seen some of the people I was dealing with—the stakes I was up against—then talk to me about ease.”

“Say more about these ‘stakes,’” the angel invited, clicking his pen again.

“Did Judea not fall?” Jeremiah asked.

“It did.”

“And did people not perish?”

“They did.”

“Well, there you have it. Stakes.”

“Yes, but even so,” the angel said, “did it help your cause? To feed this constant driving anxiety?”

“Help my cause?” Jeremiah sat up and turned to face the angel. “What are you suggesting?”

“Only that you open your eyes a bit wider,” the angel answered. “I mean, cities are always falling, are they not? People are always dying. Death always looms, and the earth will, one day, burn down to the very elements from which it came, as we all will. What matters, in the meantime, is how we embody the best of ourselves in the face of these things.”

“So, you’re suggesting I should’ve stopped caring? That I should’ve allowed suffering and unrighteousness to go on, unchallenged, because that’s just how things always are?”

“Did I say that? Goodness no, quite the contrary! By all means, do what is yours to do to ease suffering, but also also take solace in the fact that you, my friend, are a supporting actor in a much larger story. You are a mere cell in the body of a cosmos, which stretches backward into eternity and will carry on longer yet! ‘God,’ you call it. You seem to suffer under the illusion that you are, at your truest self, a separate being named ‘Jeremiah,’ with a finite amount of time and the world riding on your shoulders. Alas, you are not. You are but one expression of the Divine universe—a cosmic intelligence that is co-creating with and through you, as it does through others, and as it will continue to do long after ‘Jeremiah’ is but a forgotten memory. You are but a hole in the flute through which moves the breath of God! That’s Hafiz, I believe. Does this thought not grant ease? Joy, even, to let go and sing in harmony with the melody of God?”

“No,” Jeremiah said simply. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I am talking about the reality that if your work does not grow from a sense of peace, it will only breed further suffering and tension in those around you. Every step to peace, if it is to be effective, must, itself, be peace.”

“Charming,” Jeremiah said. “Did you come up with that yourself?”

“Oh, you flatter me. That was a skilled Buddhist teacher, I believe.”

“Are angels meant to be quoting Buddha?”

“Well, I should hope so. He offices out of the suite next door.”

Jeremiah rested his head in his hands. “This is the strangest thing that has ever happened to me.”

“Yes, I imagine so,” the angel said. “But as they say, the universe is not only stranger than you imagine, but stranger than you can imagine. Shall we move along?”

“There’s more?”

“Oh yes. Only one last bit.”

“Can it wait?”

“I’m afraid the clock is ticking.”

“Ticking to what?” Jeremiah glanced again at the clock, exasperated. It had seven arms, each moving in a different direction at a different speed. He suddenly wanted to smash it to the ground. Instead, he reminded himself what the angel had said. The only way out is through. If he wanted to get out of here, he needed to play along. “Fine,” he said, settling in on the chaise. “What is it?”

“That’s the spirit,” the angel said. He looked back to the scroll. “Therefore, thus saith the Lord,” he read. “If thou return, then will I bring thee again, and thou shalt stand before me: and if thou take forth the precious from the vile, thou shalt be as my mouth: let them return unto thee; but return not thou unto them.”

“What about it?”

“Care to elaborate?”

“I was complaining too much,” Jeremiah sighed. “I wasn’t as focused as I should’ve been. I felt like God was disappointed, and I had to make things right. Are you happy?”

“God was disappointed…” the angel echoed, making a note on his clipboard. “Fascinating. And when did you first realize that your god was emotionally abusive?”

This got Jeremiah’s attention. “Excuse me?”

“Your god,” the angel repeated. “When did you first realize she was emotionally abusive?”

“He,” Jeremiah corrected.

“If you like.”

“God isn’t… I didn’t… wait, what are you implying?” Jeremiah sat up, knocking the cup of tea to the ground where it broke once again. “Listen here you… whatever you are. It’s not up to you to question God’s ways or make accusations. It’s not up to me either. To do so is to invite judgment on your own head.”

The angel was unphased. “And we’re not calling that just a tad abusive?”

“God is the ultimate expression of love and faithfulness!”

“Then why are you always trying so hard to earn her approval?”

“His!”

“If you like.”

Jeremiah couldn’t form the right words. “Oh dear,” the angel said. “I can see I’ve insulted you again. Here, have some tea.”

Again, Jeremiah looked down to find a teacup in his hand.

“Will you stop that?! Look, I still don’t know what this is, but I’m finished here. Damn the clock and damn you. If you’re going to sit there and insult me and my god, then—”

“But that’s just it,” the angel interrupted. “Am I insulting your god, or merely your thoughts about your god? Surely you see there’s a difference. Reading through your works, I cannot help but wonder if your insistence that your god constantly judges others is, in reality, a fear that your god constantly judges you. If so, then I might argue that this fear has caused you far more problems than it has solved.”

“You need to stop.”

“Furthermore,” the angel pressed on, “I then must wonder if your fear that your god judges you actually comes from an even deeper judgment of yourself. ‘God is man writ large,’ after all, and such projection—”

“That’s enough.”

“Who was it who taught you that you are not worthy of love, just as you are? I’d put my money on your father—”

“I said enough!” Jeremiah yelled. He wanted to punch this angel in his round little face. “What’s the point of this? Why should I sit here and listen as you judge me?”

“Assess you.”

“Whatever!”

“I see this is difficult for you.” Calmly, the angel set down his clipboard. “I am sorry for that. However, I’m afraid this assessment is necessary to gauge your reaction to my feedback. Intense reactivity in the form of attachment or aversion, this is what lets us know where the work remains to be done.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about!”

“Well, I should hope not,” the angel laughed. “Otherwise, this next lesson would be superfluous.”

Jeremiah hesitated. “Next lesson?”

From the small table next to the angel’s chair, the timer gave a clear ding. The angel smiled and sat back. “And that’s our time. It has been a pleasure, as always.”

“Wait,” Jeremiah said. “What does that mean? Our time?”

“It means you’ve been placed. Our time is up.”

“I thought you said time was an Earth-based construct.”

“I also seem to recall saying something about paradox. That dualism is something you must work on. But not to worry, my melancholy friend. All shall be well and all shall be well. You have all the ‘time’ in the world.”

The angel put time in air quotes.

Jeremiah noticed that various objects in the room had begun to fade. Objects from the shelves disappeared and the light itself seemed to dim. “What’s going on?” he asked. “Where’s the room going?”

“Oh, the room goes nowhere. You, on the other hand…”

“Where am I going, then?”

“To your next lesson, of course! And I do believe this one should be a doozy.”

“Will I be back?” Jeremiah asked. His own hands had begun to fade.

“Oh, I should expect so,” the angel said. “As many times as it takes.”

“Will you stop it with the riddles?” Jeremiah said. “What does that mean?”

“It means trust the plan!” the angel answered, his voice echoing into a void. “Plans to prosper and not to harm. Plans to give you a hope and a future. Your words, yes? Give them a try!”

The angel’s smile was the last thing Jeremiah saw. Suddenly, the room dissolved entirely, as did the angel, as did the body of the man who had once been the prophet Jeremiah. There was an uncomfortably disorienting moment of sheer formlessness, then, all at once, a great clarity. For a brief, glorious moment, he remembered. He remembered everything. Of course, he wanted to say, but, of course, he had no mouth with which to say it. Just as soon as the thought had come to him, however, it left, like it was a veil he passed through. Something shifted—something he couldn’t quite perceive, and with a great, painful thrust, the world was suddenly far too bright. He felt cold as anything and was unbelievably hungry. He flailed with weak arms, letting out a loud cry in a voice he no longer recognized. Giant, unknown hands held him, and a voice cried in triumph. “It’s a girl!” He heard others begin to ooh and ahh and fuss.

He tried to speak but found that his voice no longer worked. He tried to think but found his mind suddenly incapable. The hands wrapped him in a familiar, scratchy cloth. He tried to remember the cloth’s name, but it slipped away, as did his own.

~

Feature image is Michelangelo’s depiction of the Prophet Jerimiah in the Sistine Chapel.

I love this! Ok. I’m out of words to tell you how much I enjoyed it. I’d have to highlight parts and write comments. Thank you!

Thank you, Alice! I’m glad it resonated. I hope it was as helpful to read as it was to write.

If you’re interested in future stories, feel free to check out zhelton.com. Thanks again for the gift of your attention!

This was captivating and, while out of my wheelhouse, quite comforting on this too-stark morning in this too-stark world.