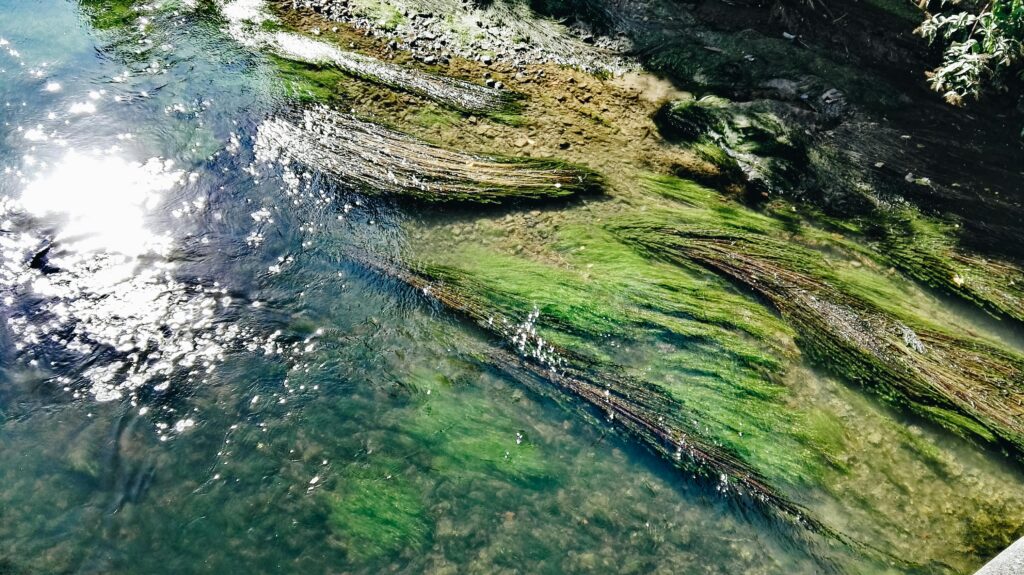

The Merced River ran wild and wide in late spring. I let the wind carry a few of my husband’s ashes into the rushing water. The upper reaches of Yosemite, where Mark hiked, backpacked, and wrote long before I knew him, were still covered in snow. El Capitan was free of climbers. My daughter watched from the bank as the ash disappeared into the river. It had been nearly three decades since Mark’s death. She only remembered him through the stories we told her and photos of her small self in his arms.

My son had clearer memories of the summer day, a year after Mark’s death, when we flung a small handful of his father’s ashes into the wind. Standing above the coastal estuary that joins the mouth of the Salmon River to the Pacific Ocean in Oregon, I promised Mark I would get to Yosemite to release a few more. Finally, I was making good on those words.

I only told close friends and my son of the reason for our trip. Though we have holidays and celebrations to mark the lives of the well-known among us, even centuries beyond their deaths, it can be difficult to explain the transformation of a relationship with the living to one with our “ordinary” dead. In fact, it is often in death that ordinary and extraordinary become larger-than-life. Imperfections fall away; the complexity of being human is translated into absolutes.

After Mark’s death, I began teaching English for speakers of other languages at a college in a rural coastal town. Many of my students were from villages in Mexico. They talked about how, on certain days, they returned to the graves of their loved ones, tidied up the grounds, brought a meal, played music and games, and celebrated the hearts still pumping and those that had stopped. They continued to care for and celebrate the lives of their dead. Whenever they spoke of those days, it was with humor and the implication that we have opportunities to keep the lines of communication open.

One of my students from South Korea told me about Chuseok, a fall festival turned public holiday, where many families dress in traditional clothing, cook traditional food, and visit the graves of their ancestors. The day is about gratitude to those who have died for what they’ve given and for their continued presence.

Hearing my students talk about their traditions for remembering the dead made me wonder how I could better witness the lives of my own loved ones long-term. Many of the rituals I knew for death were short-lived—the memorials, the letters, the nourishment in food and company. How could I touch on the lives of those loved and lost without distancing them further? What rituals would allow Mark’s presence in our lives to continue and honor the whole person he was?

I stumbled into poetry as my ritual, using the words of others to witness Mark’s life. I began in stops and starts, choosing poems that seemed a part of who he was. I wanted to include my children, hoping we could begin a ritual that would be healing and not just hokey or contrived. At winter solstice, we sat on the rocky beach of the Salmon River and read the poems out loud. That first year, my son chose a poem as well, while his sister threw rocks at the water’s edge.

The ritual evolved over the years. Early on, my children chose Shel Silverstein, Jack Prelutsky, and Naomi Shihab Nye, tapping into the prophets of living life and honoring the past. In their adolescence there was more Billy Collins, Langston Hughes, Lisel Mueller, and Elizabeth Bishop, poems with humor and agony. Every year, we’d pull the poetry books from the shelves, remembering Mark, until we found the poem for each of us that captured not only who he was, but who we were becoming. We kept our chosen poems secret until the reading.

Since I began my ritual, the community of my loved and lost has grown: mother, father, sister, friends, aunts, uncles, grandmothers, mentors, teachers, students. My landscape changes with each death. Within the privilege of growing old, a privilege denied to some of my loved ones, there is a chance to remember their lives as honestly as possible. In the ritual of reading poems, I’ve found a way to thank my loved ones, to say, “You still matter to me; this is how I hold you in my life.”

In winter, I go to the places where the dead and I built memories together. This year, I’ll make twenty stops in December and January. In a coastal marsh I’ll read a Dorianne Laux poem to my mother. I’ll shout out a poem from Ted Kooser to my father on the hill above the golf course turned to a winter wetland. I’ll stand in my own garden and read to my East-Coast uncle—the two of us bound together in eternal competition over the size of our harvest vegetables—a poem by the Oregon gardener and poet Charles Goodrich. I’ll face the Pacific in the windswept headlands my friend Andy loved and read about the durability of a seed and Lucille Clifton’s poem “Blessing the Boats.” Another Clifton poem, “The Lesson of the Falling Leaves,” will be with my sister at a small estuary where the creek flows into the sea on the beach.

I’ve come to believe that when you’ve loved well, you won’t ever want to leave the people or places you love or have them leave you. To love is to become vulnerable; love inspires, teaches, humbles, and angers; love makes us want to run away and to remain. The good, the exquisite, the mundane, the hysterically funny, and the darkest days of connection will cycle over and over again to bring us more deeply into the relationships that could be with us all the rest of our days.

In the decades since Mark’s death, I’ve sat at the river estuary where a few of his ashes once rested in the ebb and flow at the mouth of the sea. I continue to seek his counsel, just as I have asked for help and advice both from the living and from others who have died. There isn’t much I can do for them now other than use my remaining time on earth as well as I can. I’m always aware of what I have that Mark didn’t get to experience because his life ended. It’s a way of carrying and caring for someone I loved with no burden of weight. He died a loved man and a man who had loved well. I feel he is at peace, and so am I. This year, on the rocky shore of the Salmon River, I will read William Stafford’s line to him, “You were aimed from birth”—an arrow-straight truth honoring an ordinary guy who taught me, in his dying, so much about living.

This beautiful article arrived at such a good moment. I am hoping to build energy around a community ritual to honor all of our town’s ancestors, but especially those buried here.

Lovely. Thank you for sharing your family’s rituals and love of poetry with us.

A beautiful essay about how to remember our loved ones in such a holy way. Thank you for bringing to mind, favorite poets and the gift of poetry!

This inspires me to want to consider reading aloud poems to honor loved ones on anniversary dates. Maybe poems for threatened species, to honor migrant journeys, the shift in seasons, one for the solstice!

This was a gorgeous meditation on communication in the stream of life. I am inspired to share poems with more of my loved ones — and, since those close to me are not natural poetry readers, to choose 5-10 poems I’d like to have read to me when I’m gone.