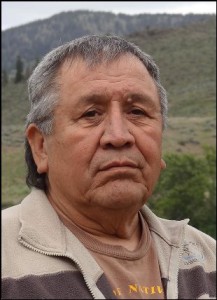

Spencer Martin, whose Indian name is Se Olum, has survived virtually every tragedy that can befall a human being. His people, the Methow, were driven from the valley named after them less than three months (July 2, 1872) after the United States government officially granted them the right to it (April 9, 1872).

Martin was born to an alcoholic mother and a father he never knew, and was raised to the age of seven by his grandparents, who taught him the old ways—until sending him to a Catholic boarding school where he was physically, emotionally, and sexually abused. That same year he also lost his grandparents, without even the chance to say goodbye. By the time he was a teenager, he was so angry and bitter he rebelled into a life of drugs, drunkenness, drug-dealing, and other crimes—a lifestyle that ultimately resulted in the deaths of his closest friends. Years later he also lost four of his five children—to accidents and other violence. Finally, after 30 years of living hell, Martin returned to himself and to the traditional medicine that has sustained Native peoples for centuries: vision quests, sweat lodges, purification, and—above all—prayer. “I thought I had beat my abusers,” he says, “but the beginning of my recovery was realizing that they had won. They put hatred in my heart.”

Martin is free of hatred now. For the last 30 years he has led many of his people—as well as non-Natives and members of other tribes—to spiritual, physical, and emotional health. He teaches the spiritual ways of his ancestors: leads vision quests, conducts initiations, and helps the dead cross over. He has worked to reconcile whites and Natives in the Methow Valley, creating with sympathetic whites an annual Reconciliation Pow-Wow that features Native dancing, drumming, handcrafts, food, and council circles. In 2007, that reconciliation work resulted in a film, Two Rivers—A Native American Reconciliation, an award-winning PBS documentary. Martin now works with the Methow Valley Interpretive Center to include Native American history, rituals, and rites of passage in its programmatic offerings to the people of the Methow.

I met Martin when I was looking for a Native American to bless the land my husband and I had purchased in the Methow Valley. There was no listing under “spiritual leader” in the Okanogan County yellow pages. I had to find my way to him by asking around. Before conducting the ceremony, Martin sat with me and asked why I was interested in blessing the land. I said I had recently become aware that humans could help to heal the Earth simply by raising their consciousness. I said that I’d like to learn how to do that if I could find someone to teach me.

Martin laughed.

Slightly offended, I asked, “Why are you laughing?”

“Because you’re sitting next to someone who could teach you,” he said.

I took him up on the offer and, over the course of the following three years, had the opportunity to conduct numerous interviews with him. He often laughed at me for being “such a European,” while I would get impatient with him for being “so Native.” The Native reliance on humor vs. the European default to impatience was one of many lessons Martin taught me. ~Leslee Goodman

Goodman: What would you say is the primary difference between indigenous and Western world views?

Martin: A basic principle of the indigenous world view is that all things in the universe are connected. We believe that we are a part of everything and that everything in the natural world is alive—conscious—even the stones, the Earth, the stars. Westerners seem to isolate themselves and think they are separate from their environment. They believe that portions of creation can be isolated from other parts; that one set of people is separate from another set; or that people are different from the animals. In the Western view, it doesn’t matter what happens to animals because we’re apart from them; superior, actually. In the indigenous world view—or what I would call “reality”—we are all a part of creation. The universe is unified. It’s inaccurate to think you can separate pieces out. Human beings are the only species who have forgotten that. When we remember, we live in balance and strive for harmony with all things. That is the most fundamental difference between the Western and indigenous world view.

Martin: A basic principle of the indigenous world view is that all things in the universe are connected. We believe that we are a part of everything and that everything in the natural world is alive—conscious—even the stones, the Earth, the stars. Westerners seem to isolate themselves and think they are separate from their environment. They believe that portions of creation can be isolated from other parts; that one set of people is separate from another set; or that people are different from the animals. In the Western view, it doesn’t matter what happens to animals because we’re apart from them; superior, actually. In the indigenous world view—or what I would call “reality”—we are all a part of creation. The universe is unified. It’s inaccurate to think you can separate pieces out. Human beings are the only species who have forgotten that. When we remember, we live in balance and strive for harmony with all things. That is the most fundamental difference between the Western and indigenous world view.

Goodman: Do indigenous people always live in harmony?

Martin: No, we’re human beings. All human beings have limitations—primarily limited understanding. But the indigenous worldview advises us that when we don’t live in harmony, we’re hurting ourselves, or fouling our own nest. Even Jesus taught this—”as you do unto the least of these—my brethren—you do unto me.” Indigenous people—at least, indigenous people who remember who they are—strive for harmony. We had that sense of unity at one time, and we lost it. We are striving to have it back.

Goodman: How did you lose it?

Martin: Through the arrival of the Europeans—who were themselves escaping oppression and abuse. As usually happens, those who had been abused became the abusers. The indigenous understanding is that all people—Europeans and Natives; Africans and Asians—are brothers. Our elders prophesied that the Europeans were coming and that destruction would follow—even though they’d never seen a European. For our own preservation, the ideal thing would have been to kill the Europeans as soon as they got off the boat. But we couldn’t do that; they were our brothers—and basically our younger brothers—so it was up to us to teach them, which remains a work in progress.

Our philosophy hasn’t changed from that time to this time, even though the majority of our people have also lost the teachings. We strive to get back to what we know about ourselves and the teaching so that we can live in balance and harmony with all things.

Goodman: Tell us what happened to your people—the Methow—when the Europeans came.

Martin: The Methow were known as very productive people, a fact that, along with the productivity of the land, made the Methow Valley the breadbasket of this entire region. The Methow people were also good at business and interacted with many other tribes, trading food for buffalo skins and other items. They kept the peace and built alliances through intermarriages.

Our people lived in tipis so that we could travel through the warmer months, going where the food was—the arrowroot, the salmon, the elderberries, and so on, as each came into season.

When winter came, we had permanent houses dug into the ground for warmth, and we stayed in those. Being of service was the primary purpose of living. If a man called himself a hunter, or a fisherman, he was obligated to make sure the elderly, the sick, and all those who couldn’t hunt or fish for themselves were fed. Someone who called himself a chief had the same obligation—to serve the community.

The people worked hard through spring, summer, and fall so that they could reserve the winter for prayer and meditation. They were hard-praying, spiritual people, and also progressive people—open to new ideas, new ways of doing things. Although it is human nature to stay in your comfort zone, the Methow were directed through prayer to leave their comfort zone and they did. In the late 1840s-early 1850s, they called a council of tribes together to try to reason with the white settlers—even though this was not a popular idea. Native people were being exterminated, but the Methow believed that understanding was the only way to stop the bloodshed. Although my people don’t live in the Methow Valley any more, we still have progressive ideas—by which I mean, we are still trying to figure out a way to get people to come to an understanding.

The man whose name I wear today, Se Olum, was also a peacemaker. Without realizing it when I began this path, my name has led me to do what he did—work to reconcile Natives and whites. Yet he is more remembered for fighting a grizzly with a knife—and living to tell about it.

Goodman: Were relations between the Natives and whites always problematic?

Martin: Fur trappers were the first to come into the Methow Valley. When winter came we would help them to survive. We were able to live in a peaceful way until more whites arrived. Once gold was discovered, the Methow people were pushed out by the cavalry—most of them at gunpoint, with only minutes to grab a few possessions. Native people still have anger because of that, although most don’t even remember why they’re angry. We need to deal with that anger. We need to remind ourselves that we are brothers and we need to deal with our anger and heal ourselves—which is the only way we can be whole again.

In our tradition, prayer is the way you become aware of your shortcomings, and we all have them. It’s really important to deal with them before you face your Creator. When I was a child, my grandfather once took me with him to a funeral, even though at that time children were not allowed. He wanted to make the point that no one leaves this world without apology or forgiveness. The way for my people to get back to health and wholeness is to forgive and to remember the truth that we are all brothers.

Goodman: Natives also say that all creation is our family. They pray for healing the Earth and “all our relations.”

Martin: Yes. Human beings have an ancient agreement to care for the animals—who are also our brothers—which most people have forgotten. My people say that there was a time when all animals could speak, but there came a point where the animals and people of the Earth were so abundant that the Creator decided to appoint one to take care of the rest. The humans and animals played a stick game and the humans won—which meant we were obligated to be the caretakers and stewards of the animals and the land. In exchange for this, the animals would sacrifice a certain of their number to provide what we needed for food. Not sacrifice themselves to be slaughtered—as happened with the buffalo, and with overfishing, and with what passes for hunting today—which has simply become killing. Our agreement was that we would honor the animals and our obligation to be their caretakers. That’s the reason we hold the salmon ceremony, for example, to honor the salmon for their sacrifice and to remember the agreement we made with them. If human beings wake up and remember our agreement to the Earth and the animals—which really is an agreement with the Creator—we could bring back the beauty of the Methow area.

Goodman: Why do you say indigenous people are the elder brothers and whites are younger?

Martin: Our history goes back much longer than the whites. Your history goes back only 4,000 to 6,000 years. Ours goes back 40,000 years. Our elders taught us that we were older, and their teachings were not about lying; they were about telling the truth. Besides, consider how white people act: they’re arrogant and disrespectful; they think they know everything; they’re risk-takers, and you can’t tell them anything. They’re just like teenagers.

Goodman: When the cavalry drove the Methow out of the valley, where did they go?

Martin: Some went into Canada. Others went just over the mountains to Malott and the area that is now the Colville Reservation. Others went downriver to Pateros.

Goodman: You are descended from other tribes, as well as the Methow.

Martin: Yes, there has always been intermarriage between the tribes. I’m descended from the Methow Chief Chiliwhist, and Chief Seattle, of the Suquamish tribe. I’m also descended from Chief Moses of the Columbia tribe, who is said to have sold out the Methow people in exchange for a small amount of cash. He had become quite the drinker, so that story is probably true. I am only the spiritual leader of the Methow people, although I often travel to the coast to perform ceremonies for people of other tribes.

Goodman: How did you become the spiritual leader?

Martin: I was taught by two of my aunts, who said that when the leaders of the clan die, I would be clan leader, as well. That may happen soon, as my aunt has cancer.

Goodman: I understand that you were raised traditionally. Can you tell us about that?

Martin: I was born in November in the town of Pateros. In accordance with the custom of our tribe, I was kept indoors for 30 days and was then taken down to the river, where my uncle made a hole in the ice with a stick so that I could be baptized—which was a Native practice, not a Christian one. In the Native tradition, we’re baptized to show that we are connected to everything—especially to water—without which there is no life. We are baptized to remember that we belong to the Earth and not just to our parents.

In my case, my parents were alcoholic, and my mother worked, so she left me in the care of my paternal grandmother, who lived on the coast. Then when my parents split up, we went to live with her parents in Malott.

I was very close to my grandfather, who taught me the old ways. He taught me to be a hunter—the essential part of which is learning to be aware and to live within the laws of nature. The first thing he taught me was not to be afraid, but he didn’t teach me in words; he taught me through experience. That’s another major difference between Natives and Europeans. Our people learn through an experience; understanding occurs later. Whites typically want to have everything explained to them first, and then perhaps they’ll consent to have an experience.

The way my grandfather taught me to have no fear was to have me go out to our well after dark and draw water. The first few times I did it, I was in such a panic to get back to the house that I spilled more water than I brought in. After I got brave enough to carry water without spilling it, he painted rocks and left them out on the hillside and again asked me to go find them after dark.

By the time I was about seven years old, my dog and I were fearless enough to go out exploring for days at a time. We’d just travel at a trot, and end up wherever we’d end up. No one worried about us. In the Native way, I was in nature. I was home. Yes, something might have happened to me, but in the Native way, no one dies before their time. It’s the Creator who says when you come in and go out of this world, so worrying has nothing to do with it.

At any rate, on one occasion my dog and I were heading up a ravine, and I felt someone watching us. I looked up, and there was a cougar on a ledge above me. We locked eyes, acknowledged each other, and my dog and I moved on. Maybe the cougar thought about eating me, but the fact that I wasn’t afraid caused him to think twice. A prey animal would have felt fear. I considered myself a hunter, not prey. Being unafraid should be true for anything we do in life.

Goodman: Why? Can’t you “feel the fear and do it anyway”?

Martin: Yes. The point is not to let fear rule your life. Fear is useful if it heightens your awareness and makes you take appropriate caution. That’s part of what my grandfather was teaching me—to learn the appropriate balance between awareness and fear. As awareness goes up, fear goes down.

Another thing my grandfather taught me is that everything has a prayer. That’s as true of hunting as anything else. In the traditional way, we pray getting ready for the hunt, during the hunt, and after the hunt. When an animal has been killed, we pray to release the spirit from the flesh and to honor it for giving up its life for us. Whatever isn’t going to be used has to be covered with fir boughs and pointed towards the east. Then there are more prayers. This is the Native way. All of life is a prayer.

There is an old longhouse—you’d call it a church—down in Malott, which is where my people would gather. There would be dinners, and all the elders would talk to us and remind us of the ways that should be. In November and December we had sweat lodges and each one of us—kids too—had to pray aloud. My uncle would go down to the river and break a hole in the ice so we could jump in after the sweat. We had a lot of practice with prayer and the importance of it. That was the beginning of my teaching in being a spiritual leader.

Goodman: How did you end up in a Christian boarding school?

Martin: My family thought I should go to this school and learn how to operate in the society outside the reservation. They thought it was going to be a good thing for me. They didn’t know what was going to happen.

Goodman: What happened?

Martin: The first day the nuns gave everyone a job, and my job was to clean toilets. I didn’t know how to clean toilets because all we had was outhouses. I was beaten for that. Plus, I’d never been around whites before, and I was scared of them. I was just a little kid. There was one white delivery man who used to come to my grandmother’s house on the coast, and he used to offer me a marble—a big one. Much as I wanted that marble, I was too scared to walk up and take it from him. So I was taken away from the people I loved and left with people I was scared of—who made demands of me I didn’t know how to fill, and who beat me for that and decided I was a problem.

Once the teachers and staff realized my family was a traditional one, they would tell me my family worshiped the devil and that I was going to go to hell. No one should talk to kids like that. There were all kinds of abuse—physical, mental, and sexual. I became really rebellious. When I got older, the teachers didn’t intimidate me anymore, and I thought I had won because they were afraid of me. But really they had won, because I was full of hatred.

When I went home at the end of my first year at school, I found out that my grandfather had died—and a few months later my grandmother—and no one had bothered to tell me. Also my dog, my hunting partner, had been shot rather than anyone having to take the trouble of feeding him. So everything that happened to me pushed me down the road to anger. I told myself I would never treat people the way I’d been treated, but when I got older, I went down that same path.

Goodman: What was that?

Martin: Anger, violence, alcoholism, drugs.

Goodman: Numbing the pain.

Martin: Or trying to make someone else feel it, too. Making other people suffer the way I suffered. It never made my pain go away. And my anger made me forget the good things my elders had taught me. I forgot a lot. For example, my grandfather had taught me all our stories in our native language, but after the boarding school, I could only remember them in English. It wasn’t until I started healing myself, over 30 years ago, that I started remembering things in Salish again.

Goodman: Can you talk about how the loss of your language has affected you—individually, and as a people?

Martin: Taking away your language is just another way of destroying you—of saying that who you are doesn’t matter—like slaughtering the buffalo, or outlawing our religion. It’s part of a strategy to destroy an individual and collective identity. When you don’t have an identity, a self, what have you got? Nothing! In fact, worse than nothing because you’ve got shame and guilt that you lost the things that were most important to you—in my case, the stories and the language my grandfather had taught me. So I covered my shame and guilt with anger and hatred. Most of my tribe is still angry—and they live among angry people so it seems normal. But it’s completely dysfunctional and works to continue the process of destruction set in motion 200 years ago.

Goodman: How did you start on the road of healing?

Martin: I was in a car with a friend of mine. We were both dealing drugs, and we’d smoked some weed and had a lot to drink besides. We knew we were approaching the end of the road in terms of the life we were leading, but we hadn’t figured out how we were going to get out of it. My friend and I had talked about it that night; we agreed that we needed to quit. We stopped at the home of a friend, and I decided to get out of the car and sleep, so another friend took my place in the car.

While I slept, the car was in an accident and both my friends were killed. Obviously, it could have been me in the passenger seat of that car. My friend had taken my spot. I also realized that I was doing the same thing to my kids that my own parents had done to me—giving them alcoholism as an example, and not being there for them.

This was in 1980, and my aunt was the leader of our clan at the time. I went to her and told her that from this day forward I would never drag my name—my Indian name, Se Olum—through the mud again. And I haven’t. She told me to go up to the mountains and deal with my issues. So for four weekends in a row I went up to Omak Mountain. I set out an altar with rocks in the shape of a circle, and I sat in it through the night. I thought about all the things that had been done to me, and about all the things I had done in return, and the only word that came out of my mouth was the “F” word. I shouted that word until I was hoarse. By the middle of the night, I was so emotionally drained that I fell asleep. When I woke up a few hours later, there were a dozen or so animals sitting in front of me—bear, cougar, coyotes, chipmunks, squirrels—all looking at me, nodding, thanking me for coming to my senses. I acknowledged them and nodded off again. When I woke up in the morning, they were gone.

After I’d sat out on the mountain for four nights, my aunt sent me to see an elder. I went with an offering of tobacco and asked the elder if she would teach me. I stayed, learning from her for as long as she wanted me to. When one elder finished with me, my aunt would send me to see another one.

A lot of the instruction was in taking orders—doing whatever the elder asked me to do: chopping firewood, cleaning house, running errands. Through it I was to learn patience and humility—that I wasn’t such a big shot; that I didn’t know very much; that I still had a temper I needed to master.

After that, my aunt wanted to me to come and ring bells for her at the Indian Shaker meetings. The Shaker Church is a Native-Christian hybrid that developed when we were forbidden to practice our own religion. The services consist mostly of singing, stomping—or what we call dancing—and ringing hand bells—all of which are a form of prayer. Prayer is the vehicle to get to a place of more understanding, of enlightenment. I thought I was helping my aunt, but it was all a part of my own spiritual growth. This entire process took about five years, by which time I felt I was ready for initiation into the enlightened world. That took place in 1986.

Goodman: Tell us about that.

Martin: It’s essentially a secret process. Since at one time all Native American religions were outlawed, it went underground. Even now, we don’t like to talk about it much. If you’re ready to undergo the experience, we tell you what it involves, but other than that, it’s better not to have preconceived notions about it. Basically, however, it involves having a total and direct spiritual experience of Reality, of Truth, rather than just an intellectual understanding of it. It’s a process of breaking down all of your mental and emotional walls, all of the conditioning that you think is what holds you together, so that you can have an experience of the Infinite. I tell people I’m not happy conducting an initiation until there are tears and snot on the walls, until there is retching and vomiting, it’s such an explosion of the person we walk around thinking we are.

There’s a vision that comes from that—from letting everything go—and then a profound understanding that follows the vision. We all think we’re alone, but we’re not and never will be.

Goodman: What do you mean, “we’re never alone”?

Martin: All of creation is alive. Everything has a spirit, and we are part of everything. Our ancestors, the spirits of those who have lived before us, are here as well. We can’t be alone. I’ve said several times in this conversation that we’re all brothers—but you are only hearing the words in your head. It’s like I’m speaking poetry to you; you’re not taking me literally. Until you have an experience of our connection—until you feel it and know it in your bones—it’s just a concept to you. You don’t live from that understanding.

The process of my initiation took place from December 31 through the end of March: 90 days. I went home afterwards a changed man. In early May my brother, who’d been initiated before me, came to visit and said “I know you have found the most beautiful thing in the world and you want to share it with everyone. But I don’t want to find you on a street corner trying to save the world. You can’t save the world! It has to save itself.” And he’s right. People have to find the truth for themselves, and when they do, it changes how they relate to the world. It’s the same as understanding we’re all connected; it’s the same as finding the peace within yourself; it’s the same as going to the mountains and dealing with your anger and hatred and exchanging it for forgiveness and peace of mind. The world’s not going to change until enough of us do that.

Goodman: You have been instrumental in a reconciliation process between whites and Natives in the Methow, as shown in the movie Two Rivers. What are some of the issues that need to be addressed in order for reconciliation to occur?

Martin: The two issues are anger and forgiveness. Reconciliation requires everyone taking responsibility for addressing the anger and the need for forgiveness in their own heart. I can call my people to address their anger, but someone needs to call the whites to get them to do their part of the healing—to address their own anger, their guilt, their sorrow, their shame. It’s not about blame. If we are family, we don’t blame each other for things that happened. We have to help each other to reconcile.

The whites from the Methow Valley often feel the need to apologize, but they should also take a look at their own anger. Their ancestors back in Europe were once indigenous—and they were exterminated, just as we were exterminated. How much of the genocide that was inflicted on us was the result of the nature-worshiping religions of Europe being destroyed before us? If Europeans couldn’t keep their indigenous ways, how were they going to allow us to keep ours?

Without dealing with their own anger, they keep projecting it onto other people.

We should also perform ceremonies for a healing of the land. In healing the land, the people will remember their connection to the land and heal themselves. I am not interested in pow-wows in themselves any longer. They’re fine for cultural celebrations, but if we’re going to reconcile, the ceremonies need more substance. How do we get to a place to accomplish that?

It’s not just about the Natives and whites, either. I’ve always said that the four tribes of the Earth—red, yellow, black and white—must come together and reason with each other to heal the Earth and stop the bloodshed between us. We all have pain from our past. We all have anger.

A few months ago I organized a dinner in Omak that included Jamaicans, who have come here to pick fruit, and Natives, who have always lived here, and Mexicans, who used to pick the fruit, and whites, who have been here for 100 years and think of themselves as Native. I sat at the table with these people and shared my thoughts and prayed with them and everyone took turns sharing about their experiences. At the end of the evening, you could feel the intensity of the emotions we had shared—and cleared. I want to go to the Methow Valley and reenact the same thing.

Goodman: What would that look like, and what good would it do?

Martin: We would invite a core group of people who would represent both Natives and whites, who would speak to purpose of our gathering. They would pray for the healing of this land and the people who have done wrong. There would be an opportunity for people to apologize on behalf of their ancestors who did wrong. The Methow people, like myself, would have to pray a song of forgiveness and ask our ancestors to forgive. Through us, the ancestors would also need to voice the anger they have carried for all these years at being yanked from their homes. It was our great-grandmothers who were forced out, but their descendants still carry that anger. They need to give voice to it so they can let it go.

Goodman: How does people saying they are sorry and giving forgiveness heal the land?

Martin: It gives voice to the ancestors. The Methow people have anger on behalf of their ancestors who were pushed out of their lands after almost 40,000 years. We have to clear that anger to become present now, and when we do that we’ll stop abusing the land. The white settlers, too, have anger. Most of the people who settled this country weren’t all that popular in the countries they left. They left because they didn’t feel at home there. They were persecuted, abused, they weren’t treated with respect. Most of them don’t remember why they’re angry; they’re just angry. In ceremony, in reconciliation, we give the ancestors a voice. We say we’re sorry and we ask forgiveness. We become present to our connection with each other—and with the Earth. That is what healing is.

Goodman: But if people don’t remember the wrong they did, or the wrong that was done them, how can they give voice to it?

Martin: Well, that’s where history helps. History can help you know what was done in the past. But your question also reveals why the work that has to be done is spiritual in nature. Once you leave this body you have greater capacity to understand things spiritually, because you shed the confines of this human form. Our understanding is limited while we’re in a body, which only means that we’re supposed to live our lives through faith and prayer. But now that they’re dead, the soldiers who drove out the Natives, who slaughtered people, know that what they did was wrong, and they need someone to speak for them, to apologize. Someone also has to be the voice for those Native Americans who were wronged and say, “I forgive my brother. To free myself, I forgive my brother.” Through that, each side would free itself.

Goodman: But how can people speak for their ancestors if they don’t have a memory of what took place?

Martin: You’d be surprised. The spirits of the ancestors speak to us. When we do a ceremony, people connect to feelings they didn’t know they had—because they didn’t have them. It was the feelings of their ancestors speaking through them. People release pain and anger and tears and grief that might go back generations. That’s the healing. We heal not just for ourselves, but for generations.

Goodman: I keep thinking of the harm that has been done to the land. The Methow is relatively pristine, but globally we have destroyed virtually every ecosystem. We are exterminating hundreds of species every day. I’m just wondering how we can do a big enough ceremony to handle all of that.

Martin: That’s one reason I’m agreeing to this interview. We need to get the message out. Most people have to be given permission to say what’s troubling them, to take action—even on their own behalf. Our prophets said “There is going to be a time when our (Native) people stand up.” So what are we waiting for? It’s our conditioning that makes us feel powerless and oppressed, but I truly believe that it’s time to heal ourselves and try to heal this world.

Goodman: How will healing ourselves heal the land?

Martin: Everything is spiritual. You can say, “That’s history, that’s in the past.” But in the spiritual realm, yesterday, today and tomorrow don’t exist. In spirit, the ancestors are here with us now.

Goodman: I still don’t understand how it heals the physical land.

Martin: That’s because you’re thinking like a Westerner. You’re thinking the humans and the land are separate. I’ve said many times that everything in the universe is connected. I realize that you understand it conceptually, but I’m telling you it’s true, literally. When you have wronged one thing, it is connected to everything; you have wronged yourself; you have wronged the land.

You said the Methow is relatively pristine now, but it was really pristine 150 years ago. The wrongs that were done to the people also affected the land. We can restore the pristine health of the land if we can right the wrongs that were done. We can do that by apologizing on behalf of the ancestors of both sides.

Goodman: If I understand yesterday’s ceremony correctly, you were acknowledging how the installation of a dam prevented the salmon from coming upriver, which was an injury done to the salmon. But you have had the healing ceremony and the dam is still there. How do we heal what is still being done to the Earth?

Martin: It’s a process. We will do another ceremony next month. But as a result of yesterday’s ceremony, this one family has now expanded their thinking and they understand a little more. They understand how the suicides that have been taking place began with the installation of the dam. They now see the significance of that wrong—the way it has affected their families—and have apologized to the salmon. When I go back, there will be more people at the ceremony, who will share the pain of their lives, and there will be more healing. How long before all those people will come to be at peace with themselves? I don’t know. I only know that anger doesn’t accomplish anything. It’s better not to have it. And I also know that if you heal one person, that person will affect someone else. I’m sharing this idea with you and if you understand what I am talking about, how many people around you will be affected by that new understanding?

Goodman: I understand that this might heal the people, but what about the land?

Martin: The land and people are connected. You heal the people, you heal the land.

Goodman: So they are going to take down the dams, dismantle freeways, stop driving cars?

Martin: Perhaps, eventually. Or perhaps the Earth will do it for us. Our prophecies say that if we don’t wake up, the Earth will shake us off like a dog shakes off fleas. But you don’t need a prophecy to tell you that. Look at the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, all the tornadoes, the drought, the record temperatures. Mother Nature has her own way of dismantling infrastructure. But my hope is that other people will be enlightened by this article and have a thirst for finding out how all things are connected. It’s a grassroots thing, one person at a time.

Goodman: Do we have enough time for that? We seem to be destroying the Earth at a pretty rapid rate.

Martin: Maybe not. Our prophecies say that things are likely to get really bad before they get better. It seems that most people only make a change when they have to; when there’s no other option. But my job is to do what I can for as long as I can, right up until the very last minute.

Goodman: What are the issues the Native people face on the Colville Reservation? What resources are being used to address them?

Martin: We’ve already talked about a lot of it. The healing of the people is the most important thing. People don’t know who they are; they’ve lost their connection to themselves, their past, to each other, and to creation. Not just Indians—people everywhere.

There’s a river that separates the Colville Reservation from the town of Omak, where the whites live. People on the reservation have a lot of anger towards the whites, but these whites didn’t do anything; it was their ancestors. This whole area could prosper if we had a working relationship with the people who live across the river from us. There are businesses in town that should thrive, but they can’t because we are at odds. Getting to know each other is therapy in itself. That’s how we tear down walls. You find out that people aren’t their stereotypes.

Goodman: How do you feel about people who romanticize, or idealize, Native Americans and their way of life?

Martin: I prefer it to those who berate us! (Laughs.) Seriously though, it’s just another form of stereotype. All people have their shortcomings, their limitations. Our people say that each of the four tribes have their own unique gift and their own limitation to overcome. Native Americans’ gift is their high spirituality; our weakness is jealousy. When I talk about our culture, I’m describing our worldview, our cosmology, our general approach to life—which is that, “In this universe, all things are connected.” Unfortunately, most of my people have lost that; they’ve lost who they are.

Goodman: I don’t think it’s only indigenous people who have lost who they are. What is the solution for finding ourselves again?

Martin: The same as it’s always been: going to the mountains, into nature. We’ve been conditioned to be fearful of that, like we might get raped by a bear or a cougar, so we don’t do it anymore. People say that once the elders are gone, the teachings will be gone. That’s true, in one sense. It’s helpful to have people to show the way. But it’s also true that the teachings won’t die with the elders because all you have to do is go up to the mountains and find them there.

Goodman: What happens when people go to the mountains?

Martin: If they know the right questions to ask they can come back enlightened. “Creator, please help me!” That’s the most important one. The most important thing is to bring yourself and your humble desire to understand to Creator.

Goodman: Can we talk about the class action suit against the Catholic Church for sexual abuses at boarding schools? How has sexual abuse affected Native people? How can we help overcome sexual abuse? How are your people being helped?

Martin: The class action suit was against a boarding school called St. Mary’s Mission and School, which is the school I attended where I and others abused, and also against other Society of Jesus schools where more than 450 others were abused sexually. Finally someone decided that we had to put an end to that. It’s like taking a stand for our own healing, saying “Enough is enough; there has to be a change; I am not going to be a victim anymore; I need to heal myself.” The first step is to acknowledge what happened and how it affected us.

Sexual abuse changes the whole world view of its victims. They are abused, they become angry, bitter, locked-up inside, and then they become abusers. Sexual abuse was never tolerated in the Native community, but now it is endemic because we are perpetuating what was done to us. There is a story among our people about a young man in the 1800s who had inappropriate relations with an underage woman. The sad thing is that they probably loved each other, and it was probably consensual. However, he could have waited until she was of age, but he didn’t. As a result, the village made the decision to execute him and put his body on a post in the village. They sent runners to all the villages to tell them why he was there. The point is that we protected our children. That’s why sexual abuse is so devastating to our people—because in the past we never let that behavior get a foothold. When it came to us, it was devastating, and we have not healed from it.

Goodman: How can Native people heal themselves from this?

Martin: First by acknowledging the problem. That was the whole point of the class action suit, which resulted in a landmark settlement from the Church—the first on behalf of Native Americans. Then you have to deal with the shame of it. In the traditional way you would pray about it in the sweat lodge. But prayer is the key element; whether you pray in a sweat lodge or not is secondary. The point is to give voice to it.

Goodman: What is the power of speaking it?

Martin: It’s like taking it out of your body. One of the most corrosive aspects of sexual abuse is that no one ever says anything. Everyone is hiding it away. So there is a real release in just saying it; in having the strength and courage to say it, to scream it out, “I am mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!”

Goodman: What is the power of a sweat lodge?

Martin: The sweat lodge symbolizes the womb of Mother Earth. You re-enter the dark womb for the purpose of being healed and reborn. There are times for chanting and singing songs in the lodge, but there are other times where everyone in the lodge must say the name of their pain. If we are doing a four-day sweat, for three days we would put a name to our pain and talk about it. On the fourth day we would move to forgiveness, letting it go, or if you can’t let it go, just let it be. Leave it in the lodge.

For forgiveness to occur, there usually has to be understanding, so we’d consider what pain the people who abused us must have felt for them to abuse another person. They were probably abused themselves. How do we stop the cycle of abuse? We believe that each of the four tribes has a gift and for Native people it is their spirituality. So we have an obligation because of our gift to find the path to enlightenment and forgive.

Goodman: It seems to me that the sweat lodge is also effective because it is so physically hot that ultimately you have to give up and surrender. You have to let go.

Martin: Yes, sweating is powerful because it is purifying, it physically releases toxins through the pores. Say you are a little ill when you went into the sweat and you were able to sweat the illness out. When you came out I would say, “Now go down to the creek and get in.” That hot and cold brings you to a place of balance, of exhilaration and enlightenment. You feel connected, open, thrilled to be alive.

Goodman: Is it true people can help to heal the Earth through changes in their consciousness? If so, how do we go about doing that?

Martin: Through discovering who you really are and what you’re here to do. The purpose of a life is never about harming the Earth and accumulating a lot of stuff. What did the Creator send you to this world to do? There are four brothers in this world—each with their own gift to share and their own limitations to overcome. That’s what you’re here to do—give your gift and overcome your limitations.

Goodman: What about Americans thinking that God gave us the country to subjugate the Native people? That we still need to go out and kill the bad guys every day in our “war on terror?” There are a lot of people running the show who don’t seem to understand we are brothers, except in the most superficial way, but when it comes to making decisions they don’t act like we are brothers.

Martin: A lot of what passes for church in this country is just a Sunday morning country club. How can people get to a place of prayer and understanding when they live in such a superficial way? People go to church, but they let the preacher do most of the work. They can daydream, or even sleep. If they feel guilty, they can put some money in the collection plate, and that’s it. Jesus died for their sins, hallelujah. They’re off the hook, no self-examination or change necessary.

Most people have a face that they put on. They are really afraid to step out from behind the mask and be an individual. We are so conditioned to play along with this game. But who made this game?

We are all judged by how much money we have in our wallets. Should that be what we are judged on? Are our lives merely the accident resulting from a sexual act between a man and a woman? The universe is far more intentional than that: everyone was sent here to do a specific job. I had to go through a maze of suffering to get to where I am today, to understand who I am and what my job is. I understand the pain of my people because I have been through all of it. I have empathy for what goes on and I have come to the place of forgiveness.

True prayer is the key to finding whatever it is we are meant to do in life. Each person has a gift and finding that is important. It’s important to find what you are meant to do here. That’s the only way we’re going to heal the Earth, ourselves, or each other. We have to stop letting other people tell us who we are and what life is about. It’s not about shopping. It’s not about being separate. In this universe all things are connected. There is no “us and them.” There’s only us.

Thank you for sharing this interview. I cannot say anything else right now because I am overwhelmed & need to process what I have just read. Ovewhelmed in the sense that I have just discovered something that moves me forward into myself. So many emotions to name. It probably sounds like gibberish, but I don’t know how to explain it any other way.

Again thank you.