Though I was a priest, mystery never touched me in my long dry years. I was an old man when it finally happened.

All in the Magdalen Order are expected to make a pilgrimage to the shrine of the holy relic of Mary the Younger at Stari Kirkevny, yet I stubbornly resisted this obligation for years.

“Too busy with parish affairs,” I told my superiors.

They helpfully assigned a junior priest to my parish. He was well-liked by all, including me. He quickly proved able at sermons, weddings, and funerals.

I lost my excuse. I had to go.

That summer I found myself in a remote province, hiking with eleven fellow pilgrims to the mountain shrine of Stari Kirkevny, each of us eager to kiss the ring of Mary Magdalene.

Some heretics say it’s her betrothal ring, given by Jesus that last night at Gethsemane. Even if it’s true, what’s the harm, I ask? Judas betrayed Jesus hours later, so no marriage was consummated.

Twelve of us left Marienbad in our pilgrim robes, walking in silence, heads covered by hoods. Being old and slow, I trudged at the back of the group, lost in solemn thoughts of a cold draught at the village inn. Near me walked a tall woman of indeterminate age.

The woman stopped. The other pilgrims didn’t notice. I passed by her, then looked back. I was going to inquire if she was alright, but she raised a slender finger to her lips, her face lost in shadow. She stepped abruptly into the woods.

Should I follow her? Should I call the other pilgrims? In the end, I did neither. I resumed walking behind the others.

A buttery moon rose over distant mountains as we reached Stari Kirkevny. It looked more like a castle than a church. An odd place to keep Mary’s ring. I was possessed by an absurd feeling that this was a false relic in a false church. Blasphemy, of course. The mountain altitude affected me.

The portal swung wide. A tall fellow, with a shaved head and glacier blue eyes, came out to greet us. As he looked us over, a queer expression contorted his face.

“You are eleven! Where is the twelfth?” he demanded in his guttural language.

The pilgrims murmured. They threw back their hoods and looked around, moonlight mixing with torchlight on their faces. No doubt it was a trick of the light, but they seemed to have the eyes of pigs. Their blue pig eyes fixed in my direction, as if the missing pilgrim was my fault.

I felt I was in danger. If I stayed with these pilgrims, entered their church, and kissed their false ring, I would never emerge again. At least not as the man I am now.

“You’re a priest of the whore,” the tall man barked in his rough tongue. “You know twelve is the required number. You bear blame for this sacrilege.”

Dread suffocated me. I fled to the woods. The pilgrims chased me with vengeful shouts. I left the path, plunging into dark underbrush, crashing into trees, wild boars grunting and squealing all around me, fireflies scattering, my boot catching a tree root. I plunged into peat and blackness.

It was still dark when I awoke. My pursuers were gone, but fireflies still flickered nearby.

Did I hear music?

A green light approached. To my amazement, a little man in a square hat emerged from the underbrush. He clutched a blade of grass on whose tip glowed a tiny lantern. He had mutton chop whiskers and brass spectacles.

A startled look crossed his face and he scampered away.

I knew I must be dreaming, but I stood up and looked for my miniature visitor. He was gone. I heard music again from the direction of the fireflies, so I headed that way, moving carefully in the dark.

A clearing pulsed with firelight and fiddles. A willow tree had fallen, leaving a broad stump. The trunk lay nearby, a nurse log sprouting toadstools and saplings.

A pilgrim’s cloak was draped over the stump.

I recognized the twelfth pilgrim. She was dressed in white. She danced barefoot on the willow stump, face aglow from the fireflies.

Not fireflies! They had faces. On the ground, around the stump, tiny people laughed and danced and played fiddles. Waving his bobbing green lantern, I recognized the little man who surprised me before.

A twig snapped under my boot. The music stopped. The woman and little people turned to look at me.

Her face was kind but her eyes sternly penetrating.

“You’re not like the others,” she decided, her voice like crickets in summer.

“No,” I admitted. “They chased me away.”

She smiled.

“Join our dance!” she said.

Fiddle music began anew, fast and merry. I slipped off my boots and entered the clearing, careful to step over the wee folk.

The lady took my hands. We danced like children under the willow moon, twirling, and laughing, until exhaustion finally turned me old again.

I woke under morning sunshine. She was gone, they were all gone. I stood and stretched my bones, sore from running and dancing.

Something glittered on the stump. Though my aching back protested, I bent down for a closer look.

A gold ring. I picked it up. It bore markings like leaves and acorns.

I slipped it on my finger and never took it off again the rest of my living days. Over the years people asked me about it. To a trusted few I told the story of my pilgrimage, including the young priest assigned to my parish.

Years passed. I retired and the younger fellow took over my duties. I lived out my days at my cottage, tending the garden, dreaming the dreams of old men.

One summer night I lay awake, looking out the garden window at a crescent moon, when I heard faint music. Someone was out there, near the willows, dressed in white.

I took off the ring and set it on my bedside table. I went out in the garden in my nightshirt. She took my hand in hers and smiled.

We walked into the woods, trailed by a procession of little folk. With each step, my bare feet sank deeper into the soil.

That was a long time ago.

My ring was placed on an altar in the parish church as an unofficial relic of Mary, known for its healing powers, though never sanctioned by the Church.

A young family lives in my cottage now. I like them. On moonlit nights, down by the old willow tree I’ve become, the children sometimes hear merry music and join our dance.

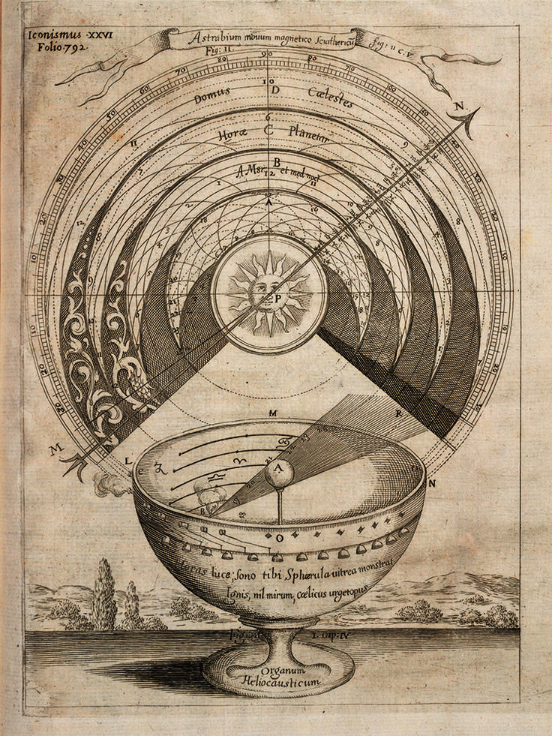

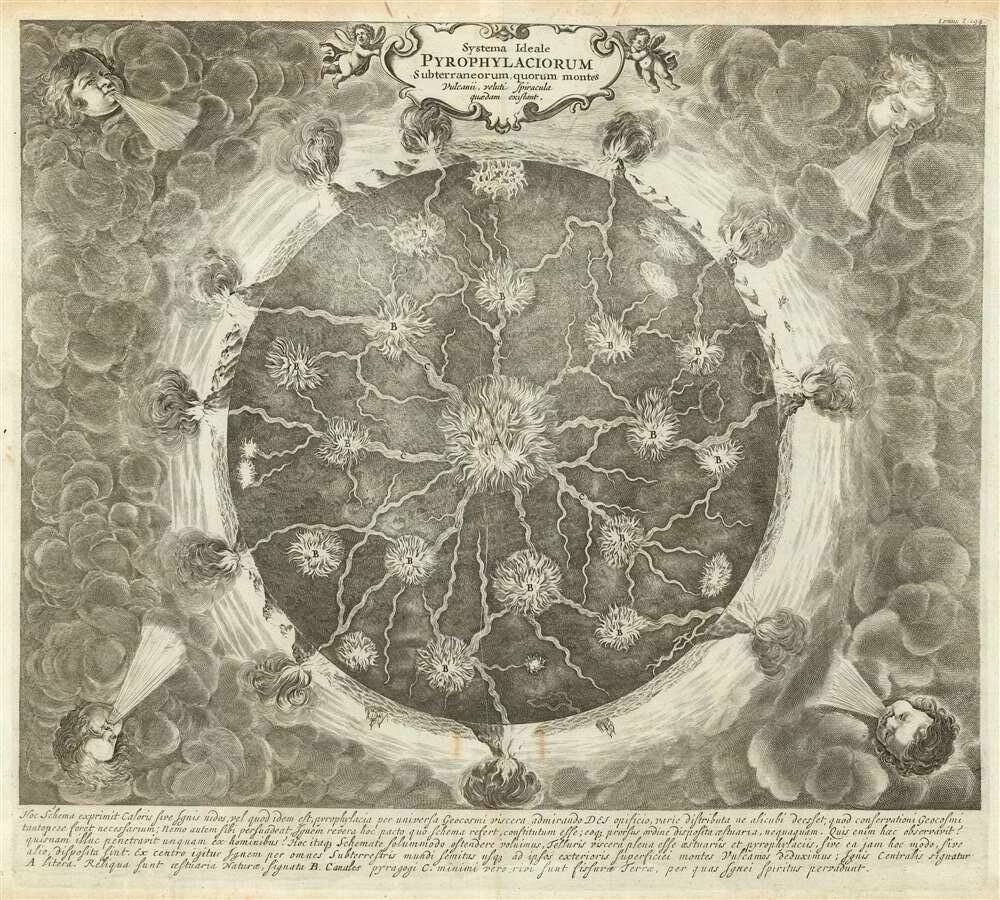

All illustrations by Athanasius Kircher. German-born Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher (c. 1601–1680) was an inventor, composer, geographer, geologist, Egyptologist, historian, adventurer, philosopher, proprietor of one of the first public museums, physicist, mathematician, naturalist, astronomer, archaeologist, [and] author of more than 40 published works. He investigated volcanoes (by having himself lowered into one while it was erupting), hieroglyphics, infectious organisms, magnetism, the relationships between languages, astronomy, and biblical scholarship. He was likely the first scientist to propose the germ theory of disease, and he invented the magic lantern or refined it from previous models. In addition to his formal publications, Kircher corresponded voluminously with learned individuals and religious figures around the world.