Mysticism has interested me since childhood. I don’t pretend to be a mystic, but I don’t dismiss those who wear the label, self-proclaimed or awarded by their followers. At age ten I sent away for Rosicrucian literature since it promised me the secrets of the universe in the ads in Popular Mechanics. Enlightenment through a body of arcane knowledge was either not forthcoming, or I forgot the secrets.

That was 1948. In 1950 I had a recurring dream three nights’ running. I was unseen, or at least unnoticed, at dusk, near a reflecting pool. There were trees about, off the concrete or tile runway around the pool. The pool was black and still. In the dim distance was a mansion. I recall the monochrome gray of coming night, the black of the trees, some reflection of the grays and blacks in the still water. Moving slowly about the pool were monks, in dark robes, hoods up, faces cloaked in black shadow. They looked like the Rosicrucians in the ads, but may have been the more purse-lipped Jesuits that seemed to populate the family album. True mystics. But I couldn’t have inherited much from them as they had no kids. That I know of. Ordinarily such a scene would have frightened me at that age, but I recall only a feeling of peace.

I asked family members about this recurring dream but the answers were unsatisfactory adult answers to a child: “Oh it’s nothing to worry about,” and a hand to my forehead for a fever check, a spoonful of paregoric before bed. I might add that I was staying at my grandmother’s that summer, along with my dad and an aunt, all devout catholics. I attended church with them until I figured out that if I was absent when they left, they would go without me. In those days a missing child didn’t signify anything other than the kid is out of hearing distance. Yell one more time. Go without him.

I will also mention at this time, for reasons that will become apparent later, that my great uncle Jack Gage Stark died during one of the days and nights of my stillwater dream. Jack was an artist, a California post impressionist of some note, and from my dad and aunt I gathered he was well thought of by the family, that he had married an “adventuress” who had divorced him and taken a good deal of his money. He later remarried her. My dad said, she left him again, this time with the rest of his money.

I didn’t know what an adventuress was but it sounded exciting. I pictured Wonder Woman or someone similarly attired. Or maybe Osa Johnson in Abercrombie & Fitch getup with a pith helmet. I was disappointed when I saw a picture of the lady in elbow length gloves and a garden hat on a patio at an estate in Santa Barbara. She didn’t look all that adventuresome, just sort of attractive, though unsmiling. This place was where she and Jack lived during one of the marriages.

Life went on. The dream never came back. But every so often something would occur to nudge my memory of it anew. Family albums with Jesuit monks, robes like those in the dream. And on entrapment Sundays when I was kept on a short leash before church, no way to gracefully escape, the service was sufficiently numinous to hold my attention, thurible-swinging puffing incense, Gregorian chant of the kyrie, the pervasive heat of the un-airconditioned church, and the various perfumes and shaving lotions of the congregation all combined to make me slightly high. At one point I fainted, hitting my head on the pew in front of me. I woke up in the shade of a tree outside, my aunt fanning me with one of those hand fans with furniture advertising on it and a picture of Jesus in sun rays.

They said my eyes rolled up in my forehead on which a knot was forming. An odd thing, when I first awoke I was way above the gathering, looking down at my prone figure in dark trousers and white shirt, my family and some others gathered around me. The priest in his vestments. The church itself, with its gray stone walls and stained glass windows seen from a vantage point I’d never had. Then I came to myself, and felt a rush of nausea which dissipated quickly. I can see this elevated scene clearly even today, as I can see the monks at the reflective pool.

I didn’t die and come back; I was merely conked while dropping from heat and religiosity trappings. I’ve read, as have you, of momentarily dead people floating above the operating table, then being sucked back into their corporeal being after witnessing unutterable loveliness. White tunnels. Loved ones gathered to meet them. That was not my experience, but it felt a tad mystical.

Shooting ahead, double my church fainting days, add in some shrooms, Jack Daniels, a little Maui bud or Kansas ditchweed, whatever we could come by at concerts, now that was mysticism. And hangovers. Blast ahead from college days, marriages, cold Coors after mowing the lawn or cooking out, no visions, just hey is this it?

But then one night I was writing what was to have become a screenplay (I was working and living in Los Angeles at the time) and going through some materials a Santa Barbara friend had sent me on Jack Stark, my great uncle, the post impressionist. She’d gotten some of his letters from a museum and among the materials was a black and white still of a silent movie starlet. She was sitting on a stone bench at a reflecting pool. The reflecting pool, same trees, mansion in the background. I had been poring over Jack’s letters, and, while they were interesting, they didn’t electrify me like this publicity still did. The location of this place was Santa Barbara. That’s where Jack Stark was the last years of his life, and where he’s buried. I don’t know about the adventuress, but I’m guessing she’s nearby. A drawing of his, “Sulky Star,” depicts a pissed-off woman in scanty circus-like costume, sitting at a dressing table though facing the viewer, arms crossed (never a good sign) scowling. This drawing got my attention early in my research on Jack’s life.

The publicity still, an eight-by-ten black-and-white glossy photo was of a pretty woman, a silent star or ingenue, seated by a reflecting pool that’s a ringer, trees and all, for the one in my recurring dream. The woman is quite small in the picture, but her hair and mode of dress would place her in the late 1920’s. While writing this I have searched old papers and files but cannot locate the picture. However I called it “Arcady” in some notes, and now know that Arcady is a colony in Montecito that featured some vistas like the one in the still, and my dream.

The family said Jack was in some silent films. I don’t dispute this as he was a strikingly handsome man; some pictures I have of him in his WWI uniform attest to this. Anyway, I followed Jack’s career from Silver City, Nevada to Taos, New Mexico and contacted the museum in Santa Barbara. When I asked the director about Jack, he chuckled and said, “Jack Stark. Yes, we have about thirty of his paintings, He was quite prolific. And quite a…dashing figure here in Santa Barbara.” When I pressed him on the last comment, he hedged and indicated that Jack may have been somewhat of a ladies’ man. Then he told me that Channing Peake, another Santa Barbara artist, was still living, and had been a good friend of my great-uncle’s.

I was just a little too late. Channing was up for a meeting, effusive in fact, and we were to meet at his ranch in Santa Ynez, but when the time came, he’d suffered a detached retina, calamitous for a still-practicing artist, and he was understandably withdrawn and not receiving guests until the eye problem could be dealt with. Time passed, and my interest in the project flagged. I was working on a major car account at the advertising agency and the pressures of the job took precedence. A follow-up call many months later found Peake in ill health and he passed away shortly thereafter.

Peake could have illuminated Jack’s career, his time in Santa Barbara, possibly his connection with the “Sulky Star” painting subject, maybe even the dusk scene at the reflecting pool. I’d found a dead ringer for the place in my dreams and it was surely within Jack’s geographical purview. But the monks? Other than the very strong Catholicism that permeated that side of my family tree, I could find no connection. Did Jesuits attend Jack’s funeral? He died during the time of the blackwater dreams. Why would I be privy to any communication, when the rest of the family (my dad, aunt, grandmother, others) who thought highly of him, and knew him well, would have been more receptive to such a visitation?

Three nights in a row, in that house that Jack had visited many times prior to my time there, the indelible yet quiet and peaceful stillwater dream. Why me? Perhaps because we shared certain traits, and I would be the artist in the family. And I would seek out an adventuress. And I would be drawn to the same geographical areas. The dream was tranquil, peaceful. I experienced no fear during the dream or awake, even though I couldn’t see the monks’ faces in the shadow of their hoods, which could have been unsettling. I just knew, somehow, nothing would harm me.

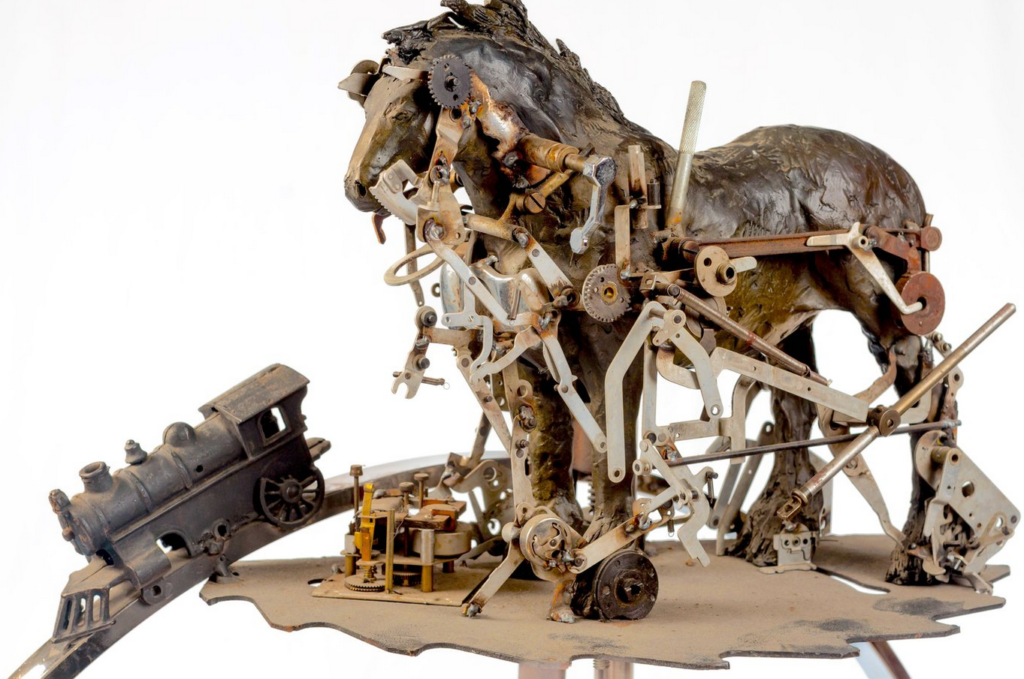

Jack died in this period and it coincided with my birthday. I was to have misadventures with adventuresses myself in a future that included art and I trod the same ground as Jack, or very near it, in Santa Barbara, Taos and Santa Fe. After reading his letters I find we both had horses and a liking and understanding for them, and we both had a longing that Hunter Thompson best expressed, “All my life my heart has sought a thing I cannot name.”

So there’s that. No pat explanation I’m afraid. It just was. And it was mystical. Ten or twelve years later I was at a house with a Scottish friend, his White West Highland Terrier, and a family of four (man, woman, two pre-teen children) who had experienced what they determined to be a poltergeist. David, my Scots friend, said his dog would, by his actions, bear them out or give some sign of an unseen presence. It was a day made for ghostbusting; windy, cold, gray.

We were all in the living room, David, me, the dog, the family, and the dog suddenly leapt up, ran to the stairs and started barking. We heard some rustling and a noise like something falling to the floor amid a series of metallic clicks. The two kids sat still and sullen. The man rose, unhurriedly, and led us upstairs to a sitting room where some curtains and a long curtain rod had fallen to the floor. The dog was pacing the room and growling. All of the curtain rings were off the rod and the curtains were across the room from the rod as if tossed there. The curtain rings were closed, so they would have to have been removed from the solid rod by sliding them off of one end.

The man, Paul, said, “These curtains were up when you came.” He sounded weary. It didn’t seem to surprise him, the odd way the curtains had been stripped from the rod, tossed aside, the rod elsewhere. “And, no, there’s no one else here who could have done it.” A cold frisson rippled along my spine. David said, “Haggis (the dog) says there’s a presence, or was. It’s gone now.” The dog sat at his feet, and scratched his ear.

Paul told us of a number of other strange goings-on. One I recall was when he opened the medicine cabinet in the bathroom a few days before, it quietly blossomed with a whole container of spray shaving cream. The entire container’s contents grew out from the open door and all over the sink, floor and wall. Other occurences included hammering on a door from inside an unoccupied room, a group of standing picture frames all slammed face down on a table at once, and light bulbs that became unscrewed.

David attributed it to the preteen youngsters, saying that disturbed children of a certain age, usually prepubescent, can discharge telekinetic energy causing the various events in that household. He told the parents that it would probably cease in a matter of weeks or months, and it did. Where David got his information I don’t know, but, once, around an Ouija board, my wife and I and David called up a 19th century Belgian parfumeur who was, supposedly a relative of mine. My forebears on one family side did emigrate from Belgium, and I’m pretty sure David didn’t know that at the time, though my first wife may have. It wasn’t the sort of thing she’d have remembered or cared about. We agreed, no more Ouija in the house, ever. It felt too guided by unseen forces. That and any further ghostbusting/poltergeist-hunting adventures would be undertaken by others. I have since seen children of similar mien to that of the kids in the poltergeist house, in horror movies. I don’t watch those anymore either.

In my own adolescent youth, when I felt powerless, and was searching for ways to modify that with mail order Charles Atlas body-building courses, ju-jitsu and Rosicrucian secrets, I discovered le voudou at the public library. I ate that up. But inscribing veve in front of a bully’s house on the sidewalk would just get me beat up again. And the doll with pins didn’t work, at least to my knowledge. One very old tome probably came closest to some alchemic workable method as it actually involved the victim’s (or appointee’s) DNA; it required fingernail clippings and/or hair. And incantations. I have the feeling this old book was a precursor to a Dan Brown novel, and if found by an evil government or SMERSH, could spell doom to humanity. It had passages that looked Chaucerian in their intermingled f’s and s’s. I’ve never located it again since.

When my grandmother died (she was Jack Stark’s sister) I recall driving over to her house days after the funeral. a house where I had spent some of the happiest hours of my life, and where the monk dream had occurred. I was seventeen. I entered the big yellow stucco house and didn’t bother turning on any lights; the house was kept dark in summertime to help cool it, and it was dark as I entered. I felt my grandmother’s presence and I said, “I came to say goodbye.” I was in the parlor that had never seen a TV, just a piano, a Victrola on which she played Caruso records, and a tall radio on which we’d dial in variety shows, WWII news, and The Shadow. The instant after I spoke I felt her presence so strongly that it washed over and through me like a wind and then it was gone. I was standing near the piano where she’d take a break from housecleaning and play Chopin, her favorite. I would stand and watch and listen. She’d smoke a Raleigh cigarette while playing (she saved the coupons) and frown against the smoke curling into her eyes.

I knew she had waited to say goodbye at the house. Now she was truly gone. While she had passed away in her upstairs bedroom, my dad had said to make my goodbyes then. I’d tried but she hadn’t recognized me. So she’d waited. And the mysterium tremendum episodes in my life, the dreams and the goodbye, seemed natural and not mystical at all.

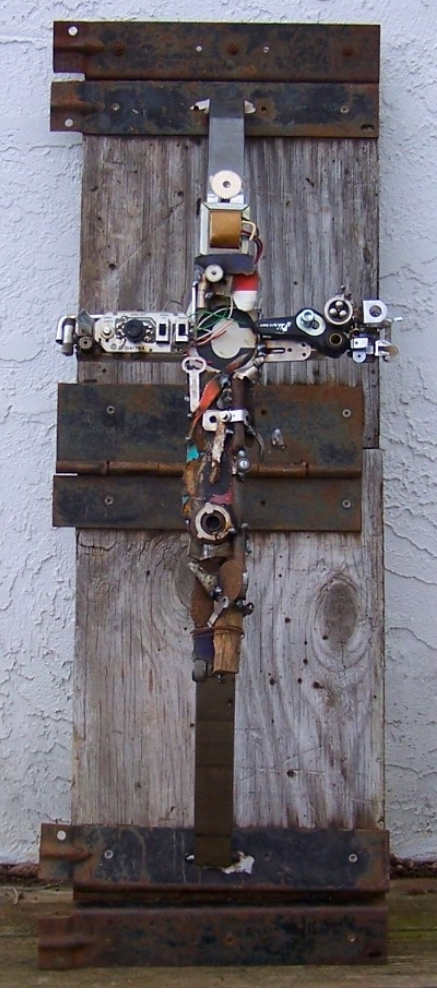

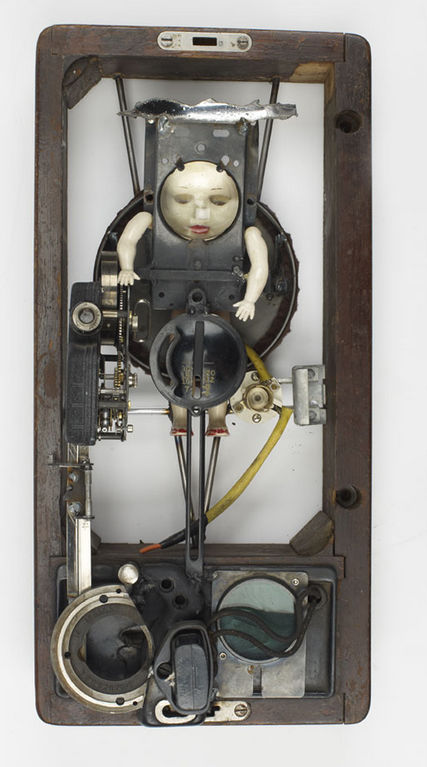

All images by artist and writer Guinotte Wise