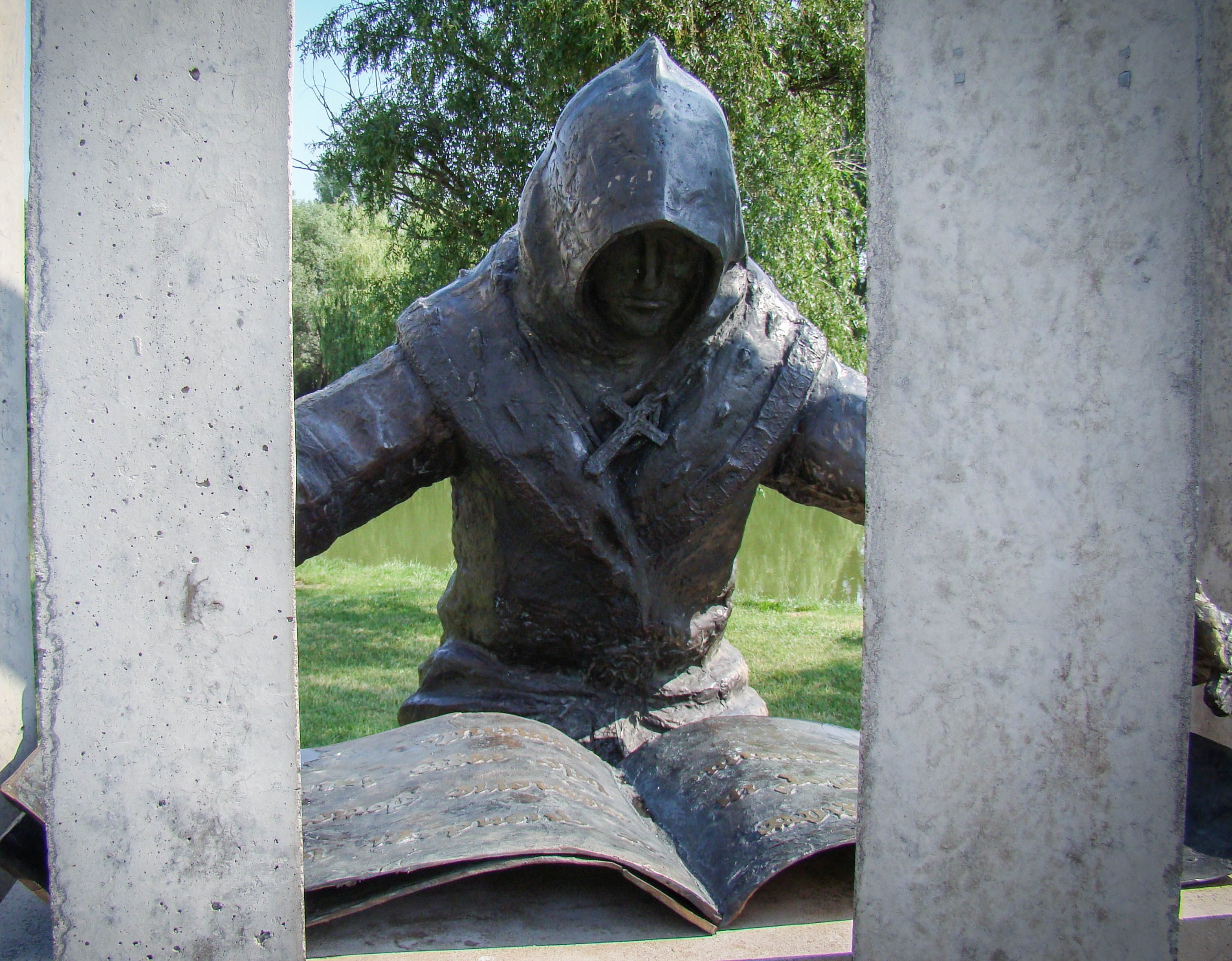

Can language capture mystical experience? Michael Olin-Hitt explores the mystic as writer.

For many of us, writing is a call with spiritual significance. We wish to use language to capture a transformative moment, whether of a state of consciousness, a level of insight, or a perception. So, we use what tools we have: metaphor, image, story.

Some of us seek to capture a fleeting moment of unordinary insight. Some of us use the act of writing in solitude to induce this level of insight. Most of us do both at the same time.

Artistic insight is not always seen as spiritual inspiration. But for me, courting and touching the Sacred in mystical awareness is the key to creative writing.

Hazrat Inayat Khan was a Muslim who brought universal Sufism to America. In his book called The Heart of Sufism, he has a chapter on Rumi, which begins with this statement:

There is not a poet in the world who is not a mystic. A poet is a mystic whether consciously or unconsciously, for no one can write poetry without inspiration, struck by some aspect of life, he brings forth a poem as a diver brings forth a pearl. (6)

To be inspired is to have the inflow of breath from a source beyond our minds. We can argue for centuries about this muse or source, but the experience of unity with something other than self is, I would argue, universal among serious artists. We can call it being “in the zone” while writing. We can, like Emerson, try to describe it as being a transparent eye-ball. We can meditate, worship, walk in the woods, or pray without ceasing to induce the state of mind. But the “inflo” of “spirit” at the heart of the word “inspiration” is reflective of mystical awareness and mysticism is a unitive experience in which we merge with the mysteries of the great Other both within and beyond the Self.

Poetry, story, memoir, drama are our means to capture the mystery of life circumstance transformed by inspiration.

The challenge for the writer is, how do we do it? How do we capture the inspired insight? How do we tell the story that transforms pain and struggle into sacred awareness? How do we convey the sense of unity or epiphany that comes only with experience and yearning? How can we do this when language is utterly inadequate? Here is how Martin Buber, the Jewish theologian, describes the compulsion of the mystic to capture the fleeting unity of consciousness:

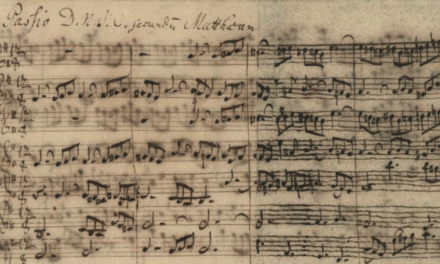

Yes it is true; the ecstatic [mystic] cannot say the unsayable. He says the other thing—images, dreams, visions—not unity. He speaks, he must speak, because the Word burns in him. . . . He does not lie who speaks of unity in images, dreams, visions, who stammer of unity.. . . He says the forms and sounds and notices that he is not saying the experience, not the ground, not the unity, and would like to stop himself and cannot, and feels the impossibility of saying it, like a seven-locked gate which he rattles, knowing that it will never open, yet he must go on rattling it. For the Word burns in him. Ecstasy is dead, stabbed in the back by Time, which cannot be mocked; but, dying, it has flung the Word into him, and the Word burns in him. And he speaks, speaks, he cannot be silent, the flame in the Word drives him, he knows that he cannot say it, yet he tries over and over again until his soul is exhausted to death and the Word leaves him. This is the exaltatio of the one who has returned into the commotion and cannot resign himself to it; this is his insurrection, the insurrection of a speaker: related to the insurrection of the poet, slighter in possession, mightier in existence, than his. This is the bending of the bow for the saying of the unsayable, an impossible task, a labor in the dark. It’s work, the confession, bears its mark. (9-10)

I would venture to say that we all know the burning of the Word. We know the work in the dark. And indeed, such confessional work bears its mark.

Like prophets, we go into our caves. We know the peace beyond the commotion of the every day, and we cannot entirely resign ourselves to this ordinary commotion. There is something deeper. Something below the surface, beyond the clatter. There are ways to transcend the commotion and seek an inspired insight that transforms human life.

I think it is transformation that draws us to writing because skillful writing transforms. Bernard McGinn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago Divinity School on writes this about the motivation to write for the mystic:

One thing that all Christian mystics have agreed on is that the experience in itself defies conceptualization and verbalization, in part or in whole. Hence, it can only be presented indirectly, partially, by a series of verbal strategies in which language is used not so much informationally as transformationally, that is, not to convey a content but to assist the hearer or reader to hope for or to achieve the same consciousness. (xvii)

As McGinn asserts, we are not reporters. We are transformers. We write to deepen our awareness and inspire others to do the same. We turn pain into poety and capture the sacred movement of the Holy.

Flannery O’Connor is one of my favorite storytellers. I admire her devotion to Catholicism even as I delight in her ability to write about twisted Protestants. In Mystery and Manners, she wrote of the challenges to write about religious insight in an age of modern doubt and skepticism. But times have changed since 1959 when she wrote this. Since that time, Modernism has given fully to Postmodernism, and now our culture seeks transformation instead of doubt or play. Skepticism about the spiritual is coming to its breaking point. People yearn for transformative experience. We see all around us a desire for the mystical. With a substantial distrust in religious institutions and their dogmatic confinements, people seek transformation where it can be found, most notably in the gothic or shadow side of the spirit.

We see the stories of the possession, the vampire, the ghost hunter, the Zombie throughout the media. I tell you, the Gothic does not exist without the Romantic. We cannot have Lord Byron and Mary Shelly without Wordsworth. We cannot have Poe without Emerson. So, shall we pick up the cultural cue and answer the call to seek the sublime and write of our journeys? I would venture to say, we have all seen or felt the beauties of the Sacred, and we cast our feeble nets to capture the momentary insight of transformation and sacred extremes.

The work is ours. And the Word burns in us to become heard.

Delivered at the Association of Writing Programs (AWP) Conference, Seattle, WA, March 2, 2014. The title of the panel was: “Writing God: Language, Craft and Sacred Experience.”

Beautifully said: “There is not a poet in the world who is not a mystic. A poet is a mystic whether consciously or unconsciously, for no one can write poetry without inspiration, struck by some aspect of life, he brings forth a poem as a diver brings forth a pearl.” Thank you so much for this insight into the link between poetry and mysticism.