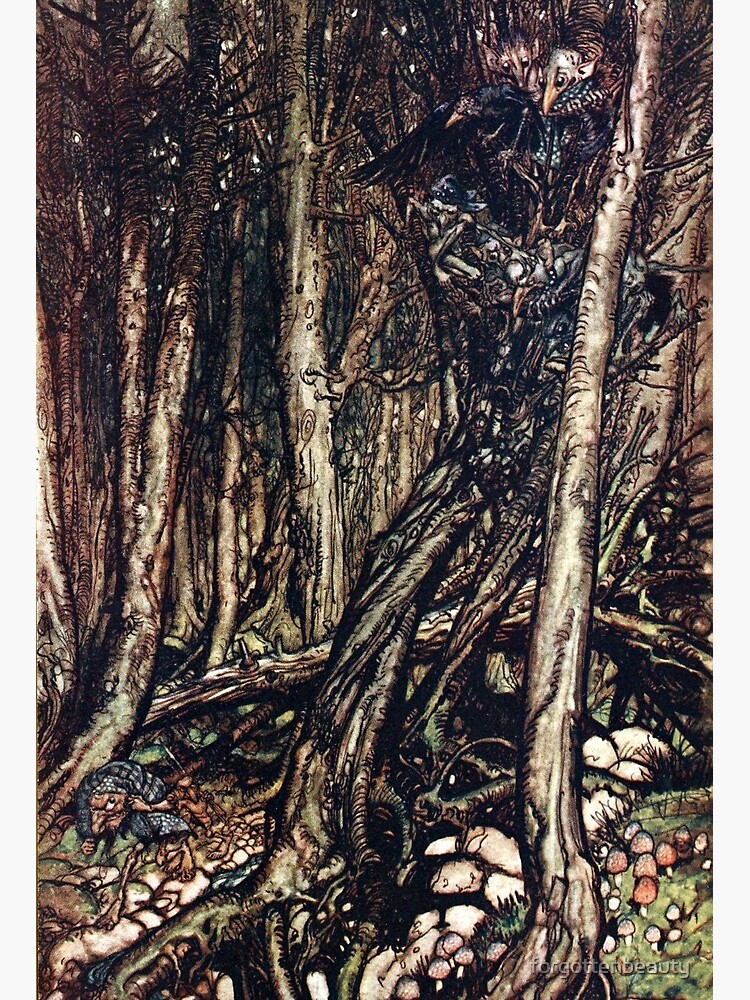

Close your eyes and imagine a fairy. It’s likely the image in your head is diminutive, tucked underneath a fly amanita mushroom, wearing dewdrops for a necklace, an acorn’s cupule on its tiny head. Or a dragonfly-sized pixie hiding inside the throat of a lily. Why, in our current imagination, are fairies so small?

In their early Celtic and European tales, they are never mentioned as being tiny, instead envisioned as the majestic Tuatha Dé Danann, riding their steeds across the verdant hills of Ireland. Many have hypothesized about the “shrinking” of fairies as they meet with Christianity. Do they represent older, ancestral practices that literally “shrank” to make way for new belief systems? The mysterious Northern Picts that seemed to have vanished altogether? Tolkien calls this “shrinking” a literary fancy and connects it to the neutralizing of the chaotic power of fairy, banishing it to the precious realm of childhood. There does seem to be some merit in this explanation.

But I am less interested in locating the exact moment when fairies became so small. Continuing to think with Tolkien, let me quote from his famous lecture, “On Fairy Stories”

“But even with regard to language it seems to me that the essential quality and aptitudes of a given language in a living monument is both more important to seize and far more difficult to make explicit than its linear history. So with regard to fairy stories, I feel that it is more interesting, and also in its way more difficult, to consider what they are, what they have become for us, and what values the long alchemic processes of time have produced in them. In Dasent’s words I would say: ‘We must be satisfied with the soup that is set before us, and not desire to see the bones of the ox out of which it has been boiled.’”

Tolkien goes on to offer that the most important aspect of fairy stories is that they are received as true. Historians have pointed out that as recently as the 16th century, fairies were seen as an unruly, sometimes beneficent, always unpredictable quality of everyday life. Manchán Magan in his rich inquiry into the Irish language 32 Words For Field, shows how fairies were understood as existing contiguous to our reality, surfacing when it suited them. They were underfoot, in the shadow of the hillside, inside the very texture of Irish words for skin and surface and genius and light.

In the world of artificial lights and fossil fuels, quantum physics and rationalism, how do we read fairy stories as true? Past a certain age it’s considered a sign of mental illness to believe in tiny beings turning milk sour and absconding with babies. Has the age of science overtaken the magical mind? Are fairies extinct?

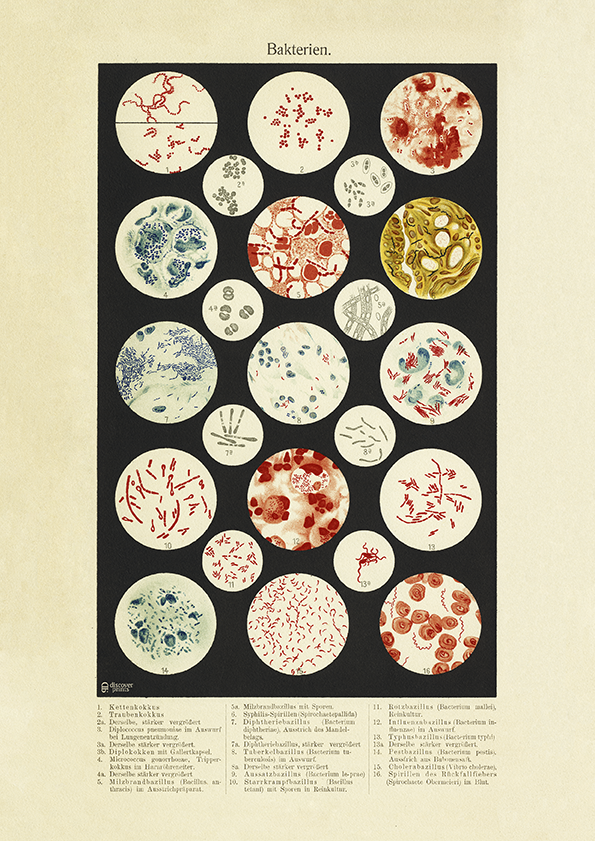

I think not. I want to take a ladle and put it into Tolkien’s “cauldron” of fairy stories that he creates in his lecture. And I want to ladle out a new kind of fairy. I think the fairies are back. And they’re even smaller. I think they got smaller, not in order to disappear, but in order to reappear, in the new age of the “true.” In stories perfectly primed for our scientifically oriented brains. Fairies are back, under the crystalline gaze of the microscope. And they have new names. I give you viruses, microbes, protozoa, fungi, tardigrades also known as “moss piglets,” dust seeds, and those other “smalls” so magical you must look through another “eye” in order to see them.

These “smalls” seem to function in a similar way to fairies. They are neither bad nor good. Microbes in our guts are a blessing, but if they migrate elsewhere in our bodies, they can cause infection. Photosynthetic bacteria in the ocean accounts for half the oxygen we breathe. Viruses can invisibly shut down the whole globe, taking out millions of human lives without ever physically appearing. But they are also responsible for the development of the human placenta. The syncitin gene in mammals that establishes a placenta is a retroviral gene that was incorporated millions of years ago.

Viruses can also provide immunity against bacterial pathogens and stimulate the immune system development of mice. Symbiotic arrangement between fungi, viruses, and algae give a tropical panic grass the ability to survive 122-degree Fahrenheit temperatures near a Yellowstone geyser. When this symbiotic arrangement has been transferred to tomato plants, they have been able to withstand similarly extreme temperatures.

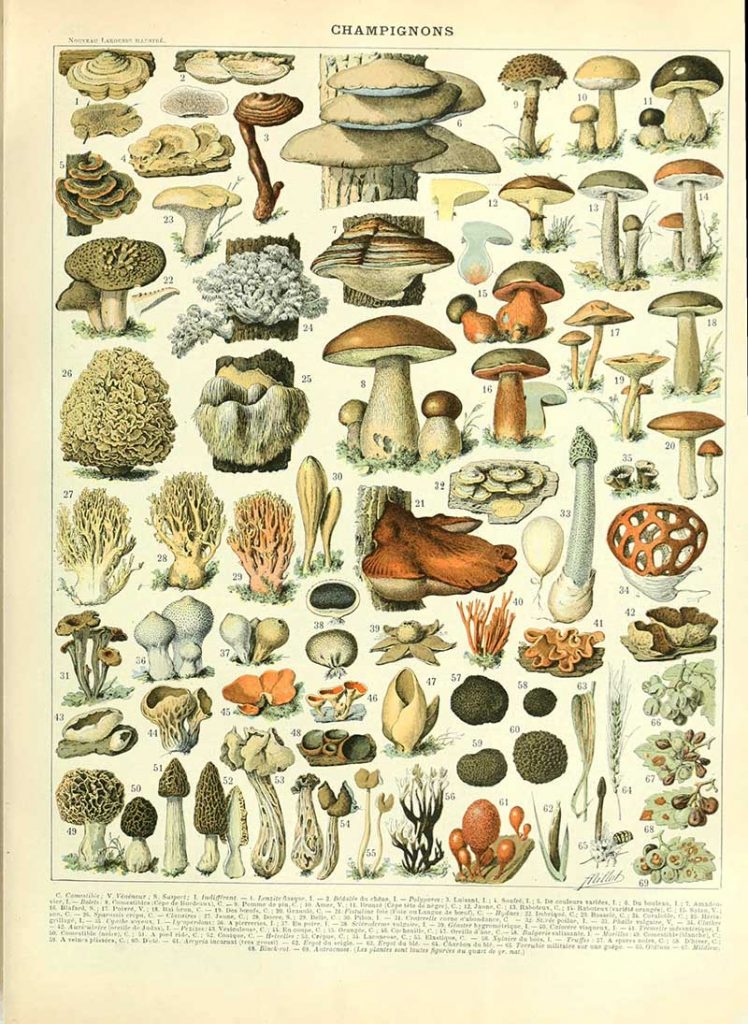

This isn’t to mention the extremely crucial role fungi play. They live in the stems and leaves of every plant, and nearly 90 percent of plants on earth depend on symbiotic fungi that weave them into complex relationships with other trees and vegetation. Mycologist Merlin Sheldrake in his book Entangled Life notes that fungi taught plants how to grow roots and are even more fundamental to the evolution of plants than leaves.

This isn’t like magic. It is magic. Beings that can topple civilizations, provide temperature-resistant armor to plants, change our brains and bodies with the smallest tweak. They embody the tricky, morally ambiguous realm of fairies. Sometimes they are helpful, sometimes they are mischievous to the point of being harmful. Mostly they are more interested in their own wild, inhuman lives than they are in our macroscopic, lumbering linear stories.

It is then very alarming that only 8 percent of all fungal species have been described, and invertebrates are largely ignored by Extinction red lists. There are spatial and taxonomic biases towards usefulness and size when it comes to biodiversity and conservation data. Even though “smalls” are the backbone of healthy soil, healthy oceans, and biodiversity in general. The 2020 Kew State of World’s Plant and Fungi Report notes that it is normal that a new plant, fungi, or bacteria is identified just as it tips into extinction.

The idea of the Anthropocene has unfortunately been conflated with the “god trick” of aerial images. Professor of Environmental Sustainability Stacy Alaimo notes that the epistemological position of the “god’s eye” removes us from situated discourse and witnessing. Landscapes are viewed colored grids from above, abstracted from the very real, polluted, intertangled complexities of the local, the living, the microscopic. Huge glaciers are better photographs for news articles than the over a billion bacteria and kilometer of folded fungi invisibly, magically humming inside a teaspoon of healthy soil.

I want to offer the magic of the microscopic as the antidote to the sterile, disembodied view of the Anthropocene. We need to stop abstracting ourselves. And come back to the very real fairies that make our food, our medicine, our guts, the very chemical soup of our own minds, possible. We need programs that identify new “smalls” well before they disappear into the world beyond story.

Locating, understanding, and naming these new species is crucial. Even amateurs can do this by going out into their backyards and taking soil samples to send off for analysis or wandering through forests with an eye for unusual plants and fungi. We also need science stories that embrace and encourage the magical element of their subject matter. Stories about bacteria and viruses and fungi as foundational in children’s education.

These new fairytales will be extremely true, and extremely small. We need to move from the passivity encouraged by a macroscopic, god’s eye view, to the penetrative, culpable position of microscopic symbiosis. The fairies don’t just live alongside us. They live inside us. Under our fingernails, in our guts, and threading through our very eyelashes. Perhaps the most profound realization of all is to realize that if we wake to their magic, we are waking up to our magic as well.

We are not separate. We are overlapping, symbiotic, inextricable. If we understand this, we will understand that our survival is contingent upon them.

Let’s start telling fairy stories again. And giving names and curious attention to the beings that playfully, dangerously, generatively inhabit our mind, eyes, words, and stories.

Further Reading

I Contain Multitudes by Ed Young

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

Elf Queens and Holy Friars by Richard Firth Green

“Your Shell on Acid: Material Immersion, Anthropocene Dissolves” by Stacy Alaimo

“On Fairy Stories” by J. R. R. Tolkien

32 Words for Field by Manchán Magan

Kew’s “State of World’s Plant and Fungi 2020”

Resources by www.geobon.org

“Move over bacteria! Viruses make their mark as mutualistic microbial symbionts” by Marilyn J. Roossinck

Thank you to the work of Siv Watkins and Micro-animism for the term “smalls.”

I stumbled upon your work merely by accident via an email that I was about to delete. But the title of the email piqued my curiosity. I did not realize it was promoting a film, Where Olive Trees Weap, by SANDS. I subscribe to their emails and find their approach to the world rather interesting—a pathway between the logic of science and a more ethereal existence.

I’ve always been trapped between the two. I’m a criminal defense lawyer, but I long to write a novel that defies explanation. It is in process. Your worldview aligns with many of my recently adopted perspectives in studying the quantum world. I always believed the universe was interconnected by a realm of consciousness that vibrates with energy, much like the novel idea of string theory.

I look forward to reading The Flowering Wand. Your reference to the Gospel of Thomas is astonishing, given how much time I have spent studying it and researching Thomas’s existence. I am incorporating a character who channels Thomas in my book.

Thank you for your contribution to the world.

Respectfully,

Lance Haley