My fingers tingled with warmth, it would not be long now, and I drove towards him under a tunnel of fir weighted with snow, past a white wooden cross sticking out of a snow bank, and through gusts of snow blowing across the road, like ghosts running from the cold.

It was expected that I would be there until his end.

In his driveway, I parked and raked at my sprawl of premature white in the rearview and pulled it into a ponytail. Beth, the social worker, called it my Witchy White and nicknamed me Saint Theresa, the Good Witch of Death, a hospice nurse wielding the magical powers of Ativan, morphine, and the ability to kill birds with a single whack from my laptop. I didn’t feel too magical right now. I checked my phone and drew a deep breath.

Atheists were always the most difficult

They accepted no stories about the waiting dead, and there was no place to ship them off too. All endings were final. Every time I had them as a patient, I felt lost and of no use, and it was in these moments, when tending to their passing, that I saw Drew and began to walk towards him, everything hallowing inside of me.

With everyone else, Beth, who is also an Episcopalian minister, and I talked about greeting lost relatives, asking family to release loved ones to a better place, God’s grace and mystery, and whatever else was meaningful to them. And in that final moment, I tingled all over, and we always did our thing of opening the window and letting the soul go and praying together beside the bed, and it could be a very moving and fulfilling experience for everyone. A good death, as we called it. Which isn’t to say everyone always go smoothly, or that someone has to be Christian for it to be a good death.

The window thing, for one, has backfired on me before. Once I opened a window beside the bed during a rainstorm and soaked the body and sheets. Another time a chickadee flew in the open window, thank God it wasn’t a crow, and flew all over the place, knocking over a lamp and clipping the metal oxygen tank with a clang before I whacked it with my laptop, striking it directly on the beak, and accidentally broke its neck. Before the family realize what I’d done, I frantically swept the bird out the front door with a broom, its poor little neck twisted and head spun backwards, and told them I’d just stunned it a little. After the passing, I took the bird with me and buried it in the backyard, my six year old daughter asking question after question about why it had to die and where it went after it died. That night, after my patient’s passing and burying the bird and all the questions, my husband’s whiskey sang to me from behind the cupboard, but I did not give in to it.

But flying birds or not, Christian, or whatever, we’ve always found a way to make it work. I’ve helped families who are Buddhist, Hindu, Mormon, Muslim, Indigenous, Jehovah’s Witness, and I have never felt like I always feel with an atheist. It unmoors everything that is your foundation in this work, and which you really must have, if you are going to survive for long, and not, as we frequently say, let it suck the life out of you.

I reached into the back seat and grabbed my nursing bag and laptop and once more breathed deeply, and carried it all with me into his home.

The botanist lay curled and sleeping on his hospital bed in the living room, the view out the window of oak and cedar and his frozen vegetable garden. Beside his bed the remains of a Christmas gift from his boys cluttered a small table — paper cups filled with seedlings, shoots uncurling towards the window, and a series of charts measuring the variables of water, sun, and fertilizer. Next to the seedlings and crumbles of black soil, lay a dog-eared academic journal and row of pill bottles.

He had two young sons and a wife who worked as some kind of lab technician at the same university as her husband. They were all quiet and intellectual, not even a television in the house. Shelves and stacks of books and journals filled nearly every room. On the walls hung photos of purple lupine dripping with beads of rain, and ancient oak spotted with black fungi. Beauty and answers in the cells of the here and now, I thought, no false promises or dreams of mystery. To the botanist, Drew was truly gone. He did not exist in an afterlife. Our visits, consequently, focused on the technical aspects of his care. They wanted to know everything inside and out, and really, he was directing his care, which was what we wanted, the healthcare team acting more in the background, with the family running the process as much as possible.

The botanist’s wife, eyes dark and exhausted behind thick lenses, sat beside her husband holding his hand. Her stained sweatpants and T-shirt were the same as two days before; her hair pulled under a baseball cap. The marathon of her care drawing to a close.

“How is he?” I asked.

She pushed up her glasses, and reported the latest: no appetite or bowel movements, swollen, purple ankles, low blood pressure, increased lethargy, labored breathing.

Like everyone else, he had wanted more time, and he fought and we fought to give him as much as possible. His goal was to make it to Christmas and he had done that. Now, it wasn’t a matter of him giving in and not fighting, but there being nothing left for him to fight with. His cancer had metastasized, spreading into his brain, and he had been in and out of it for the past week.

“Have your boys visited today?” I asked.

“They said goodbye this morning,” she said. “He’s so confused, I didn’t see much sense in them sticking around.”

Leaving you all alone, I thought. “Are the boys home now?” I asked.

“They’re upstairs on their computers.”

We rolled him on to his side for pressure relief and to check his skin. I ripped open my cuff and slid the pulse oximeter onto his finger, felt his cold wrist, and pumped and listened, everything faint and dimming. He was close to falling into a coma, and I struggled to think of the right words. To explain it was no longer about making sense of his disease, but preparing for the emotional wave to come.

The botanist mumbled something that made no sense, and my toes and fingertips burned.

“Is anyone else going to be here?” I asked. “To help you through this?”

She shook her head quickly, tucked a strand of frazzled hair behind her ear, and asked, “How much longer?”

I monitored his respirations with my smart watch. “I’ve learned not to make predictions.”

“We need to keep him comfortable,” she said.

“Do you want him to wake up?”

She shook her head. “That’s not necessary.”

“When was the last time he spoke?” I asked.

She shrugged. “Last night he babbled something about his brother, but it made no sense.”

“His brother?” I asked.

“He died in a construction accident years ago,” she said.

It was the dead, I wanted to say, trying to connect through visions and tingling, to tell us it was going to be okay. They knew he was about to pass. But telling her that would not bring her comfort, and would only lead to more questions that I could not answer.

I first experienced my tingling with the dead as a child.

It began in what everyone in my family called the Dying Room. Our house was over two hundred years old, and in that room was a bed used in the old days to lay bodies at rest for the viewing. To get to the Dying Room you had to walk through the adjacent parlor, a long, open room with a faded carpet that smelled like the attic on a hot summer afternoon. On the walls of the parlor hung framed photographs of past relatives, all stern and strict in their high collars and Sunday suits, looking down with judgement. My brothers always used to tease me about ghosts in the parlor, saying if you went in there alone and listened carefully to the old people on the wall, you could hear them complaining about the cold in their bones. I believed my brothers, but I was never scared of the ghosts. I actually loved to go in there. For the longest time as a child, I would sneak in and lie perfectly still on my back on the musty carpet and listen with every sense I could muster, staring at the stern old people, wishing for their lips to move.

Though I never heard anything but the taps of summer rain on the tin roof, the winter hiss of the radiator, and the light rattle of a nor’easter against the windowpanes, I experienced the tingling every time — a barely felt warmth in my fingertips and feet.

In that same Dying Room, when I was six, my grandmother insisted on an old-fashioned home service, and she lay in an open black metal casket with silk lace. Around her people drank and ate and silently lingered in chairs, and took turns walking past her casket to give their respects, a few using the step beside the casket, to lean in and touch my grandmother briefly. I wore my church dress and while I chewed on a baloney sandwich, the tingle began to warm my fingers and feet.

Just viewing Grandmother’s casket was not going to be enough.

I put down my plate, wiped my mouth, and slowly walked across the soft carpet toward the casket. The tingle and warmth drew me towards her, and the eyes of the wall pictures burned on my neck, more judgmental than ever. I touched Grandmother’s arm to reassure her, and crawled into the casket and lay against her. She felt so comforting and silky, warm and tingling all over, and I wanted to kiss her forehead, but the sweet, sickly smell of formaldehyde pushed me back. My mother gasped loudly and my aunt fainted onto the carpet. My father, still large and imposing before the cancer, carried me out of the casket and into the next room. He was a kind, lovely man, but he said what I had done was terribly upsetting. I told him and everyone else I was sorry, though nobody could understand why, including myself.

It was a curiosity and mystery that changed with all the deaths that would follow.

No longer was death something I ran towards, but a shadow that followed me through every neighborhood and all the soft mounds of grass holding my parents and Drew.

I suggested more morphine to the botanist’s wife and she agreed. The morphine especially was a miraculous tool. It eased anxiety, pain, made breathing easier, and facilitated what we wanted – to melt him into the covers. Morphine did not, if given correctly, cause premature death. Carefully, I drew the correct dosage with the dropper and released it into the side of his mouth.

Soon the only thing left to do was wait. They were obviously not into goodbyes, and she wasn’t a crier or a hugger, I could tell. There were also of course no scripture or prayers to fall back on and I was definitely not opening any windows. For a second, I thought of reading the periodic table out-loud before realizing how idiotic that sounded.

I wished Beth was here. She was on vacation in Bermuda, probably sitting on some beach, holding a drink with one of those little umbrellas in it, preaching to some tanned Adonis. If Beth were here, she would use her hospice superpowers to determine which stage the family was at, anger, denial, acceptance, and help them either move through it, or fully realize where they needed to be. I had more of a hospice anti-superpower. I only envisioned my patients at their most vulnerable, usually when young, and it sucked me in every time. During nearly every visit with the botanist, I had envisioned him as a young boy, studying ferns and daisies in his backyard, meticulously examining their cellular structures under a microscope, with the fascination of a young priest reading scripture. I also imagined the moment he first held his sons in his arms, or bathing them in the sink, causing me to almost tear up in front of him.

I felt restless and a strong need to do something.

“I remember him talking,” I said, “of all the seasons. Returning to the earth and the world of chemistry and all the cycles of nature. How important that was to him.”

She stared at her husband’s hands. His fingertips streaked with purple.

The silence was okay, I knew, but it was another one of my weaknesses. I always felt a need to fill it. It was also in these moments, when waiting for the passing, that Drew began to creep back in. If I didn’t fill a need, at times, it became almost unbearable.

“Is there anything I can do to help? Get you a cup of coffee, or something to eat?” I asked.

She shook her head and walked away. “I need to check my email and shower,” she said.

“I’ll get you if anything changes,” I said, feeling more anxious, the weight of memory slipping through. Holding hands in the clear water, his long soft hair and tanned shoulders, and the warmth of his body against me.

In the end, the botanist did not pass easily. His breathing would slow and he would seem to be gone, only for him to perform a heaving gasp and start up again. We couldn’t pray, hold hands, or talk of a higher power, so we only waited and watched. My hands tingled and burned brightly, and then it stopped. I searched for his heart under my stethoscope, waited the necessary two minutes, nodded to his wife, and marked the time.

She let go of his hand and kissed his forehead quickly. But she didn’t cry. She looked adrift, with no shoreline in sight. I touched her shoulder gently and she flinched. It was okay, Beth would tell me, death follows no pattern. I envisioned my patient’s wife working her grief inside for days, months, and perhaps even years, polishing and categorizing it, then finally one day, crying over a memory and cup of tea with her mother, or maybe with her oldest son while weeding in the garden. Going through what Beth called, the painful but necessary remembering.

I called the doctor, the funeral home, and prepared the body. She did not want to take part and I was uncertain if they wanted to view him one last time, so gently as possible, I removed the catheter, and slowly sponged and dried him from head to toe, covered him with a sheet, and waited for anyone in need. But the family didn’t need anything from me. They had already said goodbye and the wife said she only wanted the body removed; the boys would not be viewing what their father had become. They planned to bury his ashes beside the rose bushes in the backyard.

By the time Joe, the undertaker, and his partner arrived, it was late. They methodically zipped him in, lifted the body onto the gurney, rolled the gurney over the outside snow, and slid the body into the waiting hearse, and closed the hatch. I made another call, typed out a final note on my laptop, gathered my bags, and went to say goodbye.

The wife was sitting at her kitchen table, sipping a cup of tea. I sat beside her and was unable to resist. “Don’t hold the pain back, and then let it all go,” I said. “It’s the only way.” Too soon, I thought, the moment after I had said it.

She looked up from her tea, shaking her head. “Why do you do this?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Help people die. It’s awful.”

“It’s a calling,” I said.

The botanists’ wife sipped her tea again, looking disgusted. “It’s your drug, isn’t it?”

I shook my head, uncertain what she meant.

“You need to help others,” she said. “So you never fully feel your pain.”

Exhaustion sunk into me and I wanted to lay on the floor, curl into myself, and sleep for a long time. But she wasn’t done.

“You have more bones buried inside you than any of us.” She shook her head. “Don’t hold it back and let it move through you, my ass.”

“Is there anything else I can help you with?” I asked. I wanted to leave.

The botanist’s wife stood up. “I need to tell the boys now and you have to go.”

She walked away and did not look back.

In the dark, I walked to my car, soft flakes fluttering into my eyes, boots crunching over the snow, and placed my nursing bag and laptop on the seat beside me. I pushed back the folder of DNRs, cracked the window, found the package of crumpled Marlboros deep in the bottom of my nursing bag, knocked one out, and lit it with trembling hands. I drove home, crying and smoking my cigarette, and passed his wooden cross on the embankment.

I pulled over, and stood over his cross. It leaned sideways in the dusting snow, plastic flowers and red ribbon fluttering. And once more, I walked slowly towards Drew’s gray body on the cold metal plinth, my mother holding me up. He was my high school boyfriend. A patch of black ice and an oak tree. I pulled at the cross. It was stuck in the ice and I kicked and yanked and finally wedged it free and threw it into the black woods. If only it was that easy. I walked back to my car and lit another cigarette and drove on.

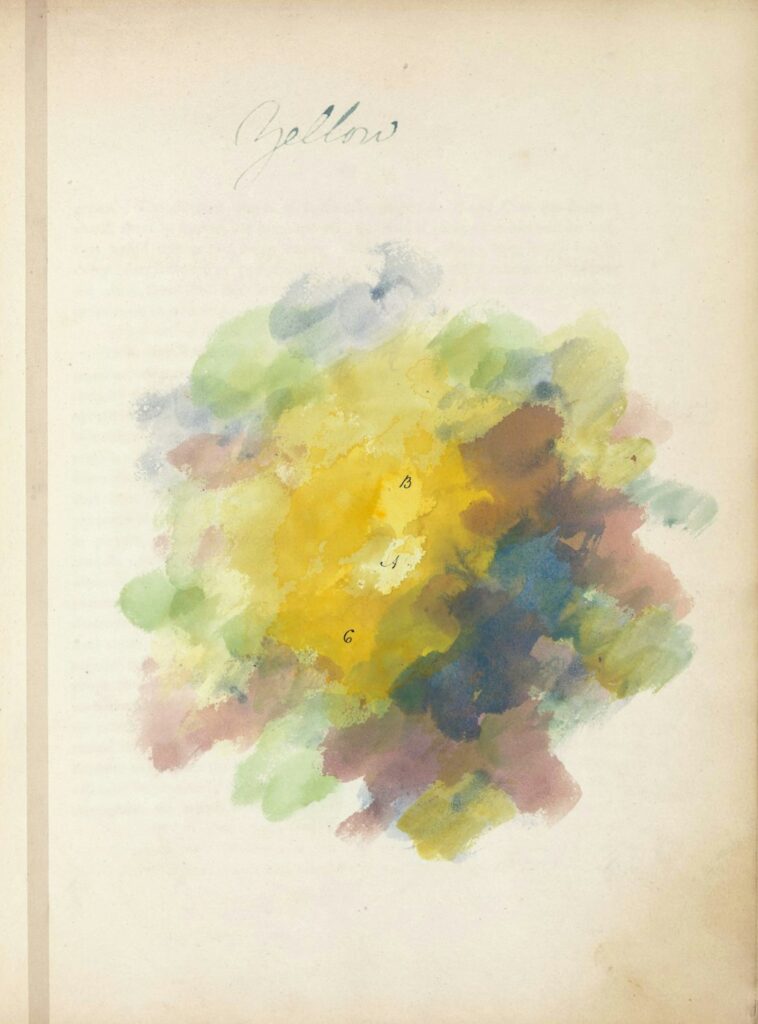

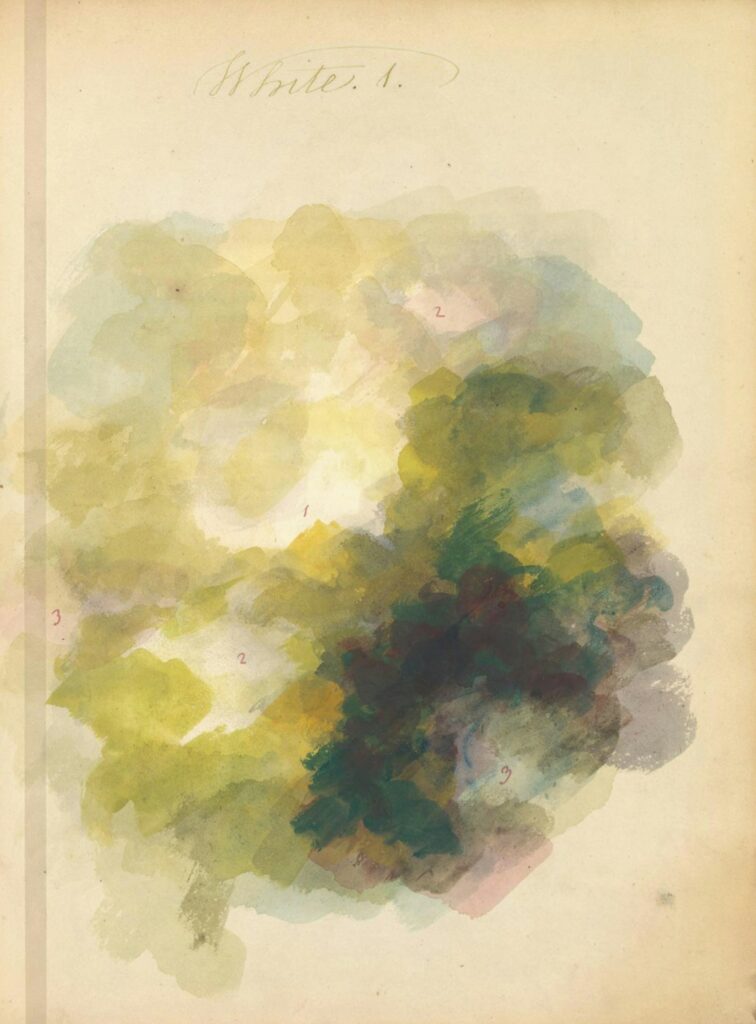

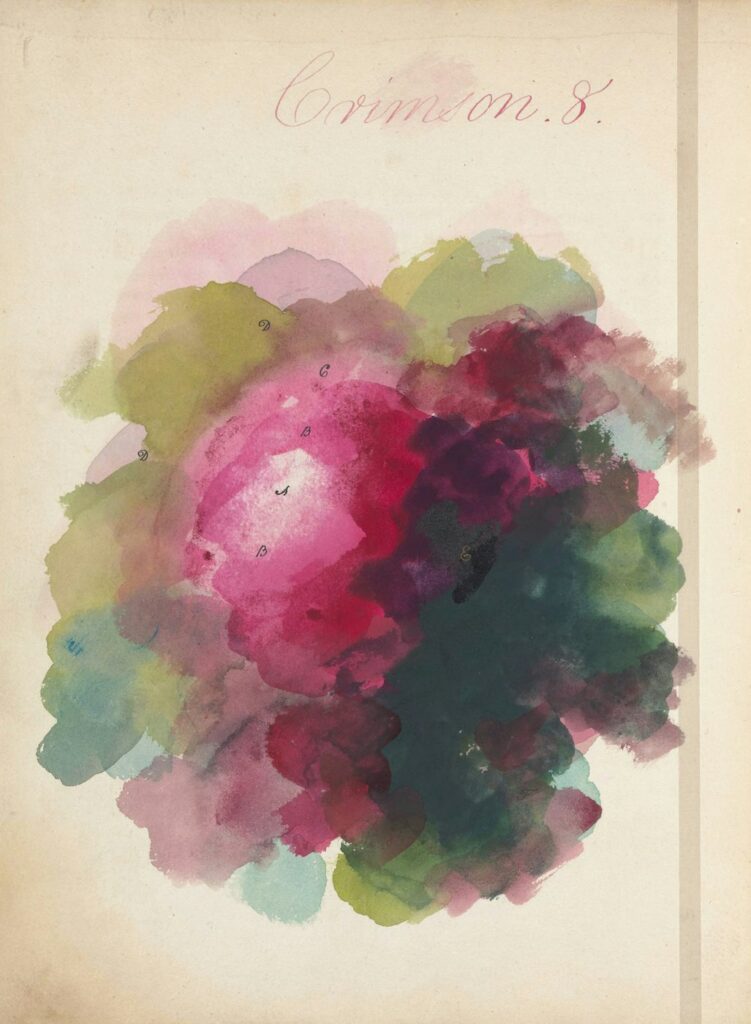

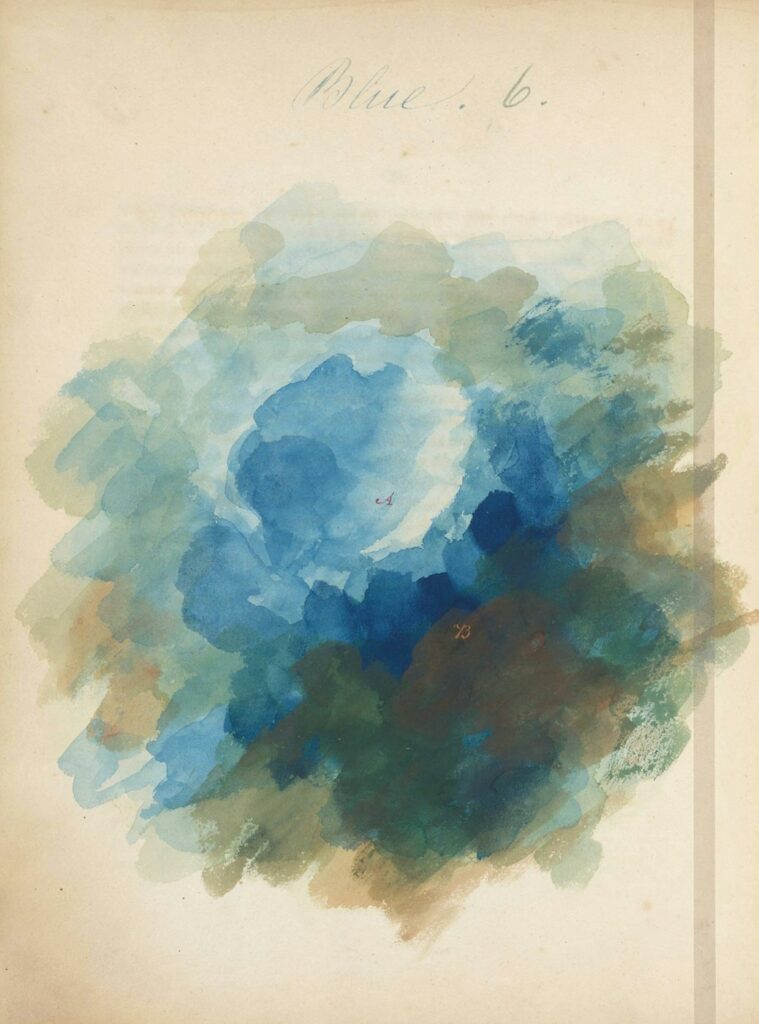

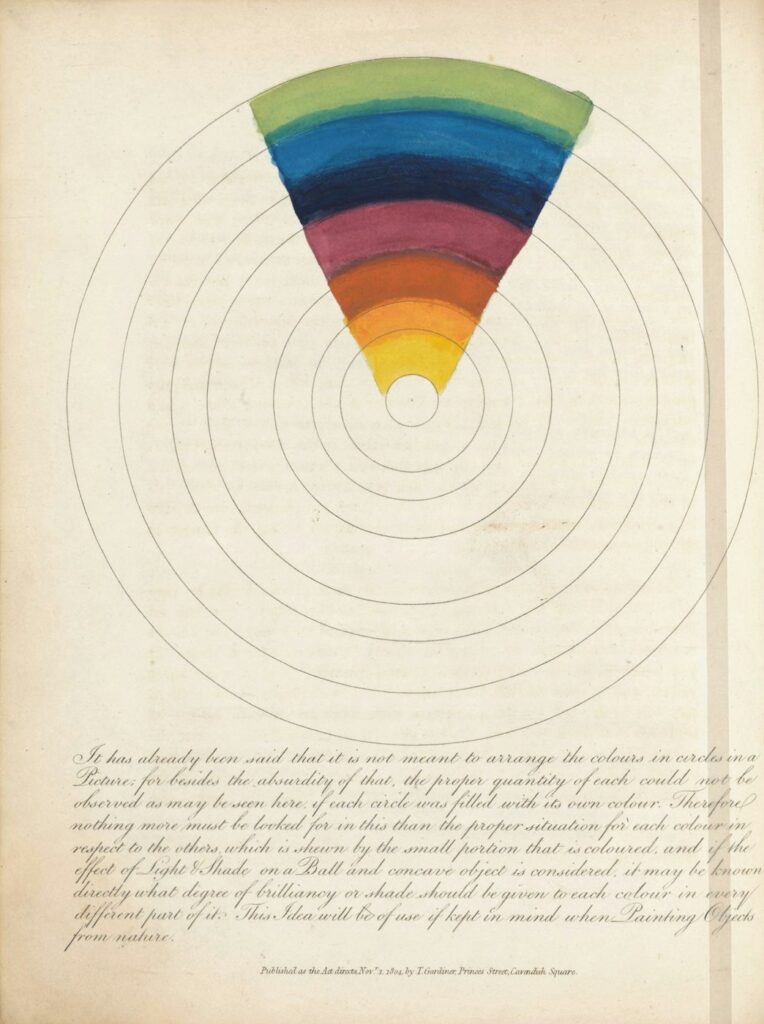

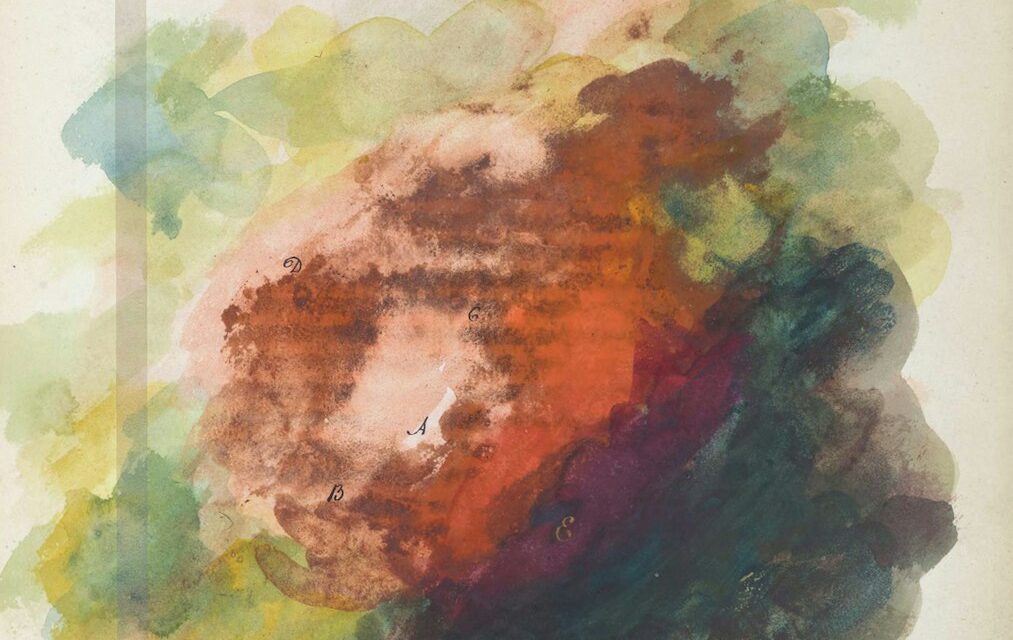

All artwork bu Mary Gartside, New Theory of Colours (1808)

Breathtaking. Which of course what this is, but it’s all I could think…thank you for this. xo