It is often said that we humans are primarily visual creatures. So much of life is tied to visual cues. We begin looking for our mother and father’s faces to see whom we belong to as soon as we are born. As we pass through childhood, we become more and more adept at visual discernment, until we have learned to read faces, read books, read signs, read situations. With its bright lights and glowing screens, modern life keeps us tied to what can be seen more than ever before. Seeing is believing, we sometimes say. For many of us, seeing is all we know.

But there is an ancient symbol that tells a different story. Known as the hamsa, it took the form of a hand with an eye superimposed over the palm, and examples of it have been unearthed throughout the world—from the Middle East to Asia to Mesoamerica. People interpret it as a sign of good luck, or as a protection to ward off “the evil eye.” But it was once a sign of the Goddess.

In the Buddhist tradition, we find statues of a bodhisattva known as Avalokiteshvara, “She Who Hears the Cries of the World.” But hearing those cries without answering them would be meaningless. That is why, in many parts of Asia, Avalokiteshvara is depicted with a thousand of these hamsa-like hands fanned out in a great circle, ready to touch every corner of the world.

Mothers know that their hands soothe. They rub their babies’ backs to put them to sleep. They caress their children’s hair when they are fretful. They press their palms to feverish foreheads when their children are sick, and when the medicine is slow, those same hands offer relief and healing of their own. Scientific studies have confirmed what people have always known—touch is therapeutic.

No wonder babies who are not held fail to thrive and die. No wonder people live longer with someone to hold. No wonder the greatest comfort we can offer to a beloved friend or family member in distress is not a litany of words but one hand laid over another.

The rosary teaches us to “see” with our hands again. Like the fingers we entwine with those of another, there is nothing more intimate, nothing more connected, than the feeling of rosary beads slipping across our palms. The rosary gets us out of our heads and into our hands.

Touch is our first language and the birthright of having a body. Touch connects us most directly to one another, to Our Lady, and to the world. That is why we must never shy away from the body when we say the rosary. We must never try to become all spirit when we pray.

Does it matter to the baby what color the mother’s blouse is

once she has opened it to nurse? Is a lover concerned

with the clothes his lover wore once she has taken them off?

Just so, you will come to me in the simplest way possible,

without concerning yourself over many words.

The Way of the Rose began when a feminist writer and her husband, a former Zen Buddhist monk, experienced an apparition of the Virgin Mary. Weaving together their own remarkable story of how they came to the rosary, their discoveries about the eco-feminist wisdom at the heart of this ancient devotion, and the life-changing revelations of the Lady herself, the authors reveal an ancestral path—available to everyone, religious or not—that returns us to the powerful healing rhythms of the natural world.

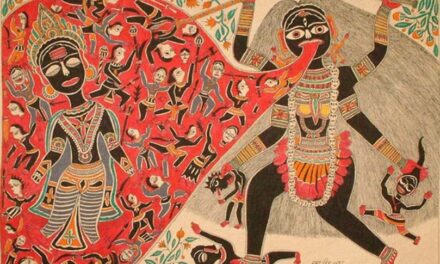

(Featured artwork by Nick Teo, CCA 3.0)