Mental health therapist Jennifer Olin-Hitt describes how sand tray therapy can help suffering people discover something profoundly sacred and whole.

Five-year-old Elijah, running his fingers through the damp sand, makes his own private rivers in which parrots stand guard. Obi Wan Kenobi and a snowman rest, half buried, on the mountainous banks of his river.

Five-year-old Elijah, running his fingers through the damp sand, makes his own private rivers in which parrots stand guard. Obi Wan Kenobi and a snowman rest, half buried, on the mountainous banks of his river.

For several minutes, Elijah had been burying trinkets and rocks all through the terrain. The boy stands up and darts back to the treasure boxes to sift through the hundreds of miniatures provided by his sand tray therapist. With all the focus of a Zen master, he methodically gathers angels, trees, train tracks, airplanes, and houses; entranced by the work of creating his world. For a few moments this child is given the power to control the curvature of rivers and the height of mountains.

Twelve months ago, Elijah’s world collapsed with the death of a parent. Any normal uncertainties of childhood have been compounded by this tragedy. In order to shore up reserves and regain footing in the wake of death, Elijah and 20 other children gather regularly at Akron Children’s Hospital for the Good Mourning Grief Group. This six-week experience is designed to offer safe space for children who grieve. Most of these children have experienced the death of a parent. Some are mourning the death of a sibling or a grandparent. All of them are navigating great tidal shifts in their young lives. The therapists and trained volunteers who lead Good Mourning meet these children on the banks of their grief.

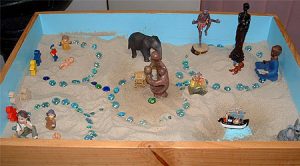

Sand tray therapy is one of the modalities used by the Good Mourning facilitators. Carol Stanley, a certified sand tray therapist and a retired school counselor, was brought into the program to implement this process with the children. Carol explained some of this method’s history. The sand tray was first developed as a therapeutic tool for work with traumatized European children by British pediatrician, Dr. Margaret Lowenfeld in the early 20th-century. Recognizing that children express themselves as much through play as through language, Dr. Lowenfeld introduced trays of sand in which children might express their thoughts and feelings by playing with miniatures. The child can position them, move them, use them to express feelings. Then, in the presence of an insightful, attentive adult, the child will tell the story of the world she has created.

Carol told me that when she worked in the school system, she often worked with a young survivor for six weeks as together they unpacked the meaning of the tray. In our Good Mourning group, each child only has one evening with a sand tray. Yet even in that short time, a child can begin to externalize the great pain that has been trapped inside his or her psyche. As a volunteer in the Good Mourning program, I am an observer to this process. I listen as a child explains her world to me. She tells me about the miniature items she chose. She explains the private logic that has guided her creation of a world within the sand tray’s boundaries. On to each item the grieving child projects a despair that she has carried, sometimes buried, for months. But now in this space, sitting on the floor beside the sand tray, hands gritty, fingernails caked with drying sand, the child has no need to apologize for her world. This is not a place to censor her tears. Sometimes the tears come as great rains. I sit with the child by his river until the crying subsides for this time.

I am a mental health therapist. I am a spiritual practitioner. I am a respecter of grief. Sand tray therapy draws me because of its ability to honor deep emotion. Over the course of years or maybe a lifetime, a sand tray therapist collects a cast of eclectic figures. From chess sets, from toy sets, from cereal boxes, from trinkets found on the beach, the sand tray practitioner gathers forms, sorts them, cherishes them, contains them until the right therapeutic moment. In the context of deep soul work, the therapist brings out the boxes and introduces the figures to the precious and suffering person who has buried both feeling and memory. As the figurines are presented, something deep within the grieving child knows that this particular object, this particular totem, is strong enough to embody the pain of his grief.

I am a mental health therapist. I am a spiritual practitioner. I am a respecter of grief. Sand tray therapy draws me because of its ability to honor deep emotion. Over the course of years or maybe a lifetime, a sand tray therapist collects a cast of eclectic figures. From chess sets, from toy sets, from cereal boxes, from trinkets found on the beach, the sand tray practitioner gathers forms, sorts them, cherishes them, contains them until the right therapeutic moment. In the context of deep soul work, the therapist brings out the boxes and introduces the figures to the precious and suffering person who has buried both feeling and memory. As the figurines are presented, something deep within the grieving child knows that this particular object, this particular totem, is strong enough to embody the pain of his grief.

As Elijah traces his river and inhabits it with parrots, he is externalizing a story that needs to be told. He relies on the only language that his feeling self can recognize – shapes and colors, tactile figurines, and gritty sand. In so doing, he is able to tell the story of his grief.

Used in this way, sand tray is an art form. Symbol becomes a tangible representation of something often ineffable. Just as the potter shapes the clay vessel and the painter covers the canvas with light and shadow, so the grieving child creates a universe in sand. Each artist churns out a vision of what is and what might be. In this way, the sand tray is akin to spiritual practice. Spiritual practice is filled with symbol in the service of hope and fortitude.

Centuries ago in a different context of human experience, the Gothic architect enabled those with weary eyes to turn their faces upward. Likewise, the Byzantine artist painted the icon that represented faith in the unseen. In indigenous cultures, costumed dance or masked drama externalized strife and resolution. Now in a 21st-century hospital, a child builds the sand mountain or hews out the valley as a visual way to express the depths of despair or yearning for hope. The movement of the child in the sand tray resembles a spiritual practice. As she carves in the sand and positions figures, one imagines the walking path of Eastern meditation, the fingering of the rosary, the sacramental rite of holding a chalice. Body externalizes the inner state of life.

Centuries ago in a different context of human experience, the Gothic architect enabled those with weary eyes to turn their faces upward. Likewise, the Byzantine artist painted the icon that represented faith in the unseen. In indigenous cultures, costumed dance or masked drama externalized strife and resolution. Now in a 21st-century hospital, a child builds the sand mountain or hews out the valley as a visual way to express the depths of despair or yearning for hope. The movement of the child in the sand tray resembles a spiritual practice. As she carves in the sand and positions figures, one imagines the walking path of Eastern meditation, the fingering of the rosary, the sacramental rite of holding a chalice. Body externalizes the inner state of life.

Carl Jung, the great 20th-century psychoanalyst, left a legacy to those who would yoke inner struggle with healing ritual. In his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, and Reflections, Jung recounted how a creative project of building a miniature model village out of stone helped him move through a major life impasse. He remembered such “play” as a child and how it calmed him. As an adult, he was inspired to pick it up again. He reported that the creative act was a starting point for significant work. Jung’s own words are as follows:

“I went on with my building game after the noon meal every day, whenever the weather permitted. As soon as I was through eating, I began playing, and continued to do so until the patients arrived; and if I was finished with my work early enough in the evening, I went back to building. In the course of this activity, my thoughts clarified, and I was able to grasp the fantasies whose presence in myself I dimly felt.

Naturally, I thought about the significance of what I was doing, and asked myself, ‘Now, really, what are you about? You are building a small town, and doing it as if it were a rite!’ I had no answer to my question, only the inner certainty that I was on the way to discovering my own myth. For the building game was only a beginning. It released a stream of fantasies which I later wrote down.

This sort of thing has been consistent with me, and at any time in my later life when I came up against a blank wall, I painted a picture or hewed a stone. Each such experience proved to be a rite d’entrée for the ideas and works that followed hard upon it.”

Buried within a grieving child lie profound experiences, memories, and feelings. The sand tray can be a womb of healing, a sacred place where expression is born. As Jung shows us, this work is not only for children. The sand tray, with its representative objects, can help the suffering person of any age express the flow of grief. As Joseph Campbell writes in his sweeping volume, Creative Mythology, “…mythological symbols touch and exhilarate centers of life beyond the reach of vocabularies of reason and coercion.”

Children work out their own creative myths with symbols, gritty sand, and the tray as a container. In this context, myth does not at all imply something irrelevant or silly. Rather, in keeping with Margaret Lowenfeld, Carl Jung, and Joseph Campbell, the myths that are born in the sand imply something profoundly sacred and whole.

By the end of the sand tray evening, Elijah had constructed his universe of healing. In our processing moments, the group of children sat on their haunches, huddled around his tray to listen to his story. With symbolic imagination in full throttle, Elijah explained the important truths about his world of parrots and Star Wars heroes: “This rocket ship represents my dad’s car. Then Obi Wan died. The snowman died. These parrots died. These parrots still live…”

His story trailed off into rivulets and pockets of plot line that seemed to defy logic. But each of these threads helped Elijah to weave a unified plot line of grief and recovery. Elijah’s grief is certainly not complete, if it ever will be. In fact, one rule of sand tray is that the scene is impermanent. As they worked, the children knew the trays would eventually be put away after the young participants had gone home to their families. Now that the figurines are back in their boxes and the sand is settled back in its storage room at the hospital, my hope is that Elijah’s hands remember the feeling of channeling that river, that his fingertips remember the touch of the sentinel parrots. That this moment of sand tray will serve to help him walk the labyrinth of his world and to express the buried grief.

Note: This article is not based upon an actual person or case. Elijah is a composite of several children and several situations.