Padma Venkatraman is an award-winning author. Her three novels, published in the Young Adult category, are A Time to Dance, Island’s End and Climbing the Stairs. She is an oceanographer and has worked as chief scientist on oceanographic ships, spent time under the sea, directed a school, and lived in five countries. She was born in Chennai, a city in the south of India.

Padma Venkatraman is an award-winning author. Her three novels, published in the Young Adult category, are A Time to Dance, Island’s End and Climbing the Stairs. She is an oceanographer and has worked as chief scientist on oceanographic ships, spent time under the sea, directed a school, and lived in five countries. She was born in Chennai, a city in the south of India.

Note from publisher: I first met Padma Venkatraman at the Associated Writing Programs 2017 conference in Washington DC. She was a presenter on a panel on religion in young adult novels. From her presentation, I knew she would be a perfect subject for a Braided Way interview. She captivated me with the “braided” nature of her talk. She said, “there is one truth which we see from different lenses,” and continued, “Books are a means to compassion: they are a compassion package.” It is a delight for me to publish this interview, conducted and written by Layn Palmer, a University of Mount Union student and intern to Braided Way Magazine.

-Michael Olin-Hitt

Braided Way: How has travel and your work in oceanography impacted your understanding of other cultures and your own sense of spirituality?

Padma Venkatraman: I’ve lived in (not just visited) five countries: India, The United Kingdom, Germany, The United Arab Emirates, and, of course, America, which I now call home. Whenever one lives in a land, one gets to know people. I think most people who’ve made good friends with people of different cultures, races, and religions must appreciate the similarities amongst us as human beings, at the very least. In some cases, as in mine, one begins to see an underlying oneness in humanity that transcends outward difference.

Being born Hindu and growing up in India was vital in terms of shaping my spirituality. Hindus believe that each religion is no more than a different path to the same ultimate goal. Although Hindu society has allowed itself to become so divisive and many Hindus act in ways that are abhorrent to me, and, in my opinion, against the core truths of the religion, I still consider myself Hindu, because of the immense depth of this religion’s spirituality – and its deep and abiding acceptance that all souls are equal. There are other aspects of the religion that I believe are the ultimate truth – that God is the power of Goodness that can take shape in different ways at different times; that no one human being or one religious book holds the ultimate key.

Then again, I’m convinced our souls are spiritual, not religious. There’s no Hindu soul or Christian soul, any more than there’s a white soul or a brown soul, an Indian soul or an American soul. An accident of birth has made me what I am today. Who knows what culture I’ll identify with in my next life! And yes, the theory of reincarnation is one I find more amenable than many other theories of what happens once we die – which might have to do with my Hindu heritage.

As for oceanography, being on the ocean, living on a ship, even just standing on the shore of the ocean is a spiritual experience. I love experiencing my own smallness and insignificance each time I do this, because its also an experience of the vastness, the immensity of time and space. And every aspect of science and mathematics that I’ve studied leaves me with a deep wonder for the universe. If that’s not spiritual, what is?

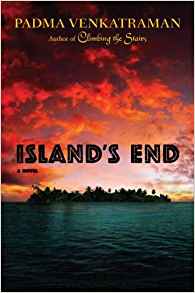

BW: In Island’s End, Uido has several visions throughout the novel,  moments when the lines of reality blur and Uido herself seems unsure what exactly has happened. What was your inspiration for these visions? Have you had any experiences like the ones Uido had on her journey to become an oko-jumu?

moments when the lines of reality blur and Uido herself seems unsure what exactly has happened. What was your inspiration for these visions? Have you had any experiences like the ones Uido had on her journey to become an oko-jumu?

Venkatraman: I had a near-death experience when I was in my late teens. I was bitten by a viper and almost lost my life. It’s a miracle that I am alive and that I did not have an amputation. This experience seems most closely related to my third novel, A Time To Dance, which is about a young girl who experiences spiritual awakening. This experience also, however, was immensely important in shaping my spirituality. Among other things, when one undergoes extreme pain (I refused painkillers when I was hospitalized), when one is face-to-face with one’s mortality, the lines between what we are conditioned to think of as “real” and what we normally refer to as “unreal” become blurred. Perhaps because of the snake bite, although I’ve spent many years studying a scientifically and mathematically rigorous field, I feel certain there’s more to life and the universe than we can conceive with our limited perceptions. To actual go into that experience, though, is more than I care to do here. To attempt to summarize the awe and beauty I felt would be to trivialize the experience.

BW: At the end of Island’s End, Uido leads her tribe in moving toward harmony with a more modernized society. The need for different cultures to find middle ground and work with each other instead of against is a pressing issue in modern society. What do you think people need to do to create a more peaceful/understanding world? How do you think religious and spiritual learning can help this process?

Venkatraman: Ultimately, unless we’re willing to not just “tolerate” one another but actually embrace one another, we’ll never enjoy peace or true understanding. I do believe that if we approach religious and spiritual learning with openness, we’ll be able to see, with astounding clarity, that each of us has a unique path – but that all our paths do lead to the same ultimate goal, whether we call it God or not. I mean, some of the people who have the greatest courage in this world that I’ve met are agnostic or atheistic. I think to work toward peace, we have to come together to realize that while we may enjoy endlessly debating the finer points of difference in terms of what we feel happens after we die or before we’re born or who or what God is or isn’t, it’s much more important to recognize and accept that we are equal. Not just equal in terms of man-made laws, but also equal in terms of an eternal spiritual law that exists, eternally, beyond the confines of religious beliefs.

BW: In the author’s note in Island’s End, you say that you created a fictitious island culture rather than try to portray one specific culture. What were your concerns when creating this culture and religion? What research helped make sure your creation accurately portrayed reality?

Venkatraman: An amazing number of authors who are white have written without complete understanding about non-white cultures and religious traditions. I’m brown-skinned, of course, but I’m not part of the culture that I depict in Island’s End, not wholly, anyway. So I wanted to be sure I didn’t write in the vein of colonial arrogance that I so often see and detest. I did a tremendous amount of work to get Island’s End right – I lived on the Andamans and I read books and research articles for years (over a decade) before I actually wrote the novel. Even so, I felt it was more respectful to consciously avoid trying to see from within a culture that I wasn’t born into, but instead create a culture very much like – but not precisely like – the culture on which my protagonist’s was based. That way, I could acknowledge, respectfully, the culture that inspired my work, without trying to appropriate it. I felt it was a humbler way to do things.

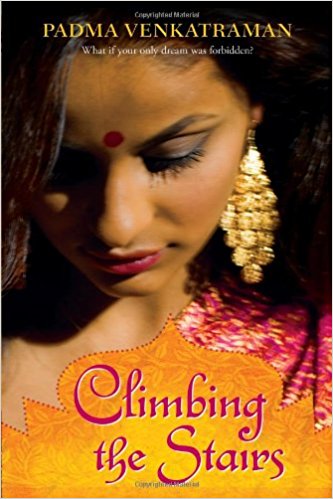

BW: Your novel Climbing the Stairs puts the main character, Vidya, through many hardships, from seeing her father beaten senseless by the British to having to live with an abusive matriarch at her extended family’s household. Is Vidya’s reaction to her family’s situation common for Indian youths? How have these traditions changed since the period depicted in Climbing the Stairs?

BW: Your novel Climbing the Stairs puts the main character, Vidya, through many hardships, from seeing her father beaten senseless by the British to having to live with an abusive matriarch at her extended family’s household. Is Vidya’s reaction to her family’s situation common for Indian youths? How have these traditions changed since the period depicted in Climbing the Stairs?

Venkatraman: India’s large population ensures that there’s a huge variation in the kinds of families that exist. In any society, there are always extremes and exceptions. In a society as large as India’s there’s a huge breadth of youth experience, even within a particular religious subset.

That said, in general, there aren’t quite as many extended families as in Vidya’s time (although, thankfully, it’s quite common, still, for children to care for their aging parents in Indian culture). Also, women aren’t quite as oppressed, as they were in the days depicted in Climbing the Stairs. At least, not officially! Caste oppression is illegal, too.

Then again, there is still tremendous caste prejudice that prevails or even predominates in certain walks of life and in certain states in India. It’s also still a very macho culture. Worst of all, many people unthinkingly perpetuate some of the ridiculous customs they were raised with – such as treating women like untouchables when they have their periods. I know South Asian Indian Americans who continue such nonsense, even in this country, which is truly sad. Many Hindus don’t bother to study the spirituality of their religion and are content to try and force silly customs on their children, customs that reflect, at best, merely the outward trappings of the Hindu religion, and, at worst, those aspects of Hinduism that “have descended to the pots and pans” as the great sage Vivekananda so correctly put it. Partly as a result of this, many youth who have a Hindu background, whether they live in India or outside it, don’t identify with the religion. As with every religion, there is a distressing divide between philosophy and practice, spirituality and society.

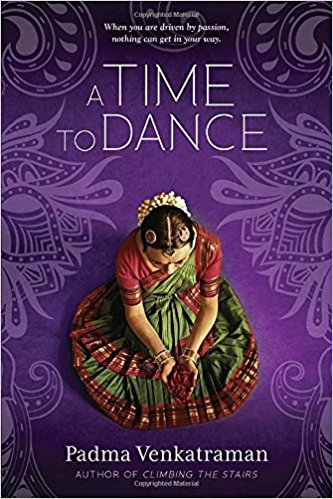

BW: Your latest novel, A Time To Dance, is among the few books that deals  with a young person’s spiritual awakening that is accessible to a young adult audience. Much of your work tackles subjects of religion and spirituality. Has writing about these themes made marketing your work to a younger audience difficult?

with a young person’s spiritual awakening that is accessible to a young adult audience. Much of your work tackles subjects of religion and spirituality. Has writing about these themes made marketing your work to a younger audience difficult?

Venkatraman: A Time to Dance, I am immensely grateful to acknowledge, was wonderfully well received. It was released to starred reviews in five respected review journals – which is an incredible honor – and it went on to receive many of the highest honors in the young adult world, and won many awards. My editor, agent, and publisher have staunchly supported the work, and I thank them for it.

Despite the book’s critical acclaim, however, it hasn’t sold as well as books that have more conventional protagonists and themes. Books that become blockbuster bestsellers for young adults tend not to be about spirituality. In particular, I’ve faced prejudice, overt and subtle, because A Time to Dance is about a young person’s spiritual discovery as seen through the lens of the Hindu religion. Hindus tend to be uncomfortable about this, especially if they live in the United States, where the book was released. And, given that Christianity is the predominant religion in America, there’s a great deal of discomfort associated with a protagonist who isn’t part of the majority religion. More times than I care to remember, I’ve been requested to keep religion out of the discussion even if questioned about it by a school audience. I respect such requests, but I don’t think those who make them understand that they’re reacting to the fact that my protagonists aren’t Christian, basically. There are many books that are accepted as classics, recommended, and unquestioningly celebrated, in which protagonists’ Christian backgrounds are portrayed in clarity and detail.

But then, it’s immensely humbling to know that A Time to Dance is, according to people who are more knowledgeable about young adult literature than I am, the first young adult novel to tackle, as its main theme, a young person’s discovery of spirituality within the Hindu religion. If I achieve nothing more in my life, I’m overjoyed that I was the vehicle to bring this book into being, here and now.

BW: A Time to Dance has been referred to as “A Siddhartha for Girls” and as “the La Vita Nuova of Bharatanatyam.” Would you like to comment on any aspect of the feminine divine?

Penkatraman: To have my work compared to Hesse’s and Dante’s – well, compliments don’t come higher than that. A Time to Dance is about a dancer who progresses, in a sense as the male protagonist in La Vita Nuova does, in her understanding of love – from Eros (erotic love) to Charis (love of others) to Agape (love of God, or, as I think of it, love of The Other). Her spiritual understanding grows, although at the end of it she’s still a work in progress, not a realized soul; her journey has just begun, it is nowhere near the end that Hesse’s male protagonist attains. Both these other works of literature refer to the female aspect of divinity – at least in passing – but the quest isn’t undertaken by a female.

We’re so used to seeing male heroes. We’re so used to thinking of male saints and male seers. Even in India, where images of Goddesses impress themselves on the psyche, the male aspect of divinity is stressed. I think this preponderance of the male needs to be counteracted – by celebrating more of women, historical and literary female characters, who are spiritual.

This gets back to the idea that we are all the same, and yet, differences need to be understood and celebrated. If we focus on one religion or one gender, if we exclude or excessively promote one physical or material manifestation of the divine and ignore another, then aren’t we promoting inequity? Doesn’t inequity often lead to discord? To move toward world peace, to move toward cultural acceptance, to move toward a true embrace of all religious paths as equal (although we’ll surely each subscribe to different paths depending on our individuality), we need to visualize the divine in as many ways as we can. We need to envision a world where a variety of religious ideas can be celebrated, with the understanding that an underlying thread of spiritual similarity unites us.

Finally, given that I’ve used the word “religious” so often in this interview, I’d like to end by clarifying that I include the scientific path in my world view. The worldview born in Europe insists that science and religion are immiscible. My opinion, however, is that science is merely another lens that some human beings choose—no different, in essence, from any specific religious path – because to me, both science and religion are no more than two radically different ways of looking at the world (just as Christianity and Judaism are different ways of perceiving the world, though they are not quite so radically different). Some argue that to even speak a soul is unscientific – but to me, regardless of how any scientist chooses to think, a rigid scientific outlook is merely a path that has no need for any idea of “God” and a path where questions are emphasized.