The Republic of the Marshall Islands, 2010

I feel their eyes watching me – hundreds, maybe thousands of them, peering out from the cement cracks as I coast to a stop. Rust flakes off the cleat at my touch. My peripheral vision registers dozens of stragglers scurrying for darkness while I make fast the dinghy.

I dislike these dock bugs. Their primordial feel and myriad legs make me uneasy. They were one of the first creatures to step on land and will likely outlive us all, even the roaches. I admit my loathing is a bit unfair; they don’t actually hurt anyone. Yet, there’s something unsettling in the greyness of these bugs – a flatness, as if their souls have been stripped of all light for some unknown crime.

As their eyes creep over me, I unload the dinghy. Will they crawl out of hiding so I can see them more clearly? I want to look into those grey faces under too-long antennae and ask them why they lurk. That’s what it is – what I dislike about them – all that lurking.

I go about my errands at the market and return along the broken road. The sweaty imprint on my shirt matches the shape of my backpack. My arms, longer now under the load of groceries, tell me the walk back was too far. My curled fingers ache. With a sigh, I set my bags on the dock. A few bugs scatter.

The dinghy rocks gently as I step in and load my tropical bounty of fresh fruit and vegetables. To prevent unwanted visitors, I am supposed to wash all produce in bleach and dunk the bags in the ocean before bringing them on board. I gave up that fastidious practice after watching a cockroach land on deck while anchored 300 meters from shore. Its massive wings let me know that if it preferred a sailboat home, then that was how it was going to be.

I pull the choke, set the throttle, and yank the starter. The little motor spurts to life. As I unfasten the dinghy, I notice an antenna twitching in a crevice. It’s unusual for the dock bugs to show themselves once they go into their cement seclusion. It feels like an invitation.

It is a living creature. I am supposed to love it. I close my eyes for a moment and try to feel love for these bugs.

I cannot. I don’t know why.

I toss the painter into the dinghy and motor away with an abstract sense of failure.

New Zealand and British Columbia, Canada, 2011-2020

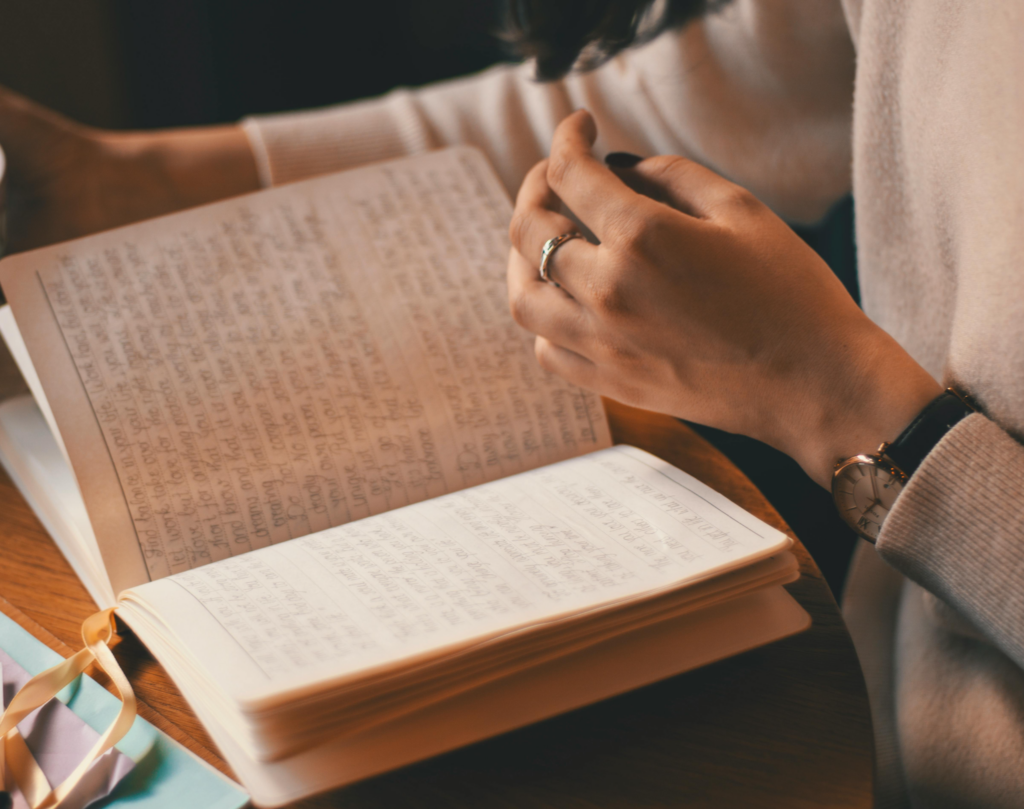

I sat on the floor of the retreat centre and watched the heart held in front of me.

My broken heart. It hurt.

It was my second year of teacher training. I sailed into these masterly teachings at the end of my voyage back to New Zealand. It felt like the entire reason for my journey was to meet Yuan Tze and embrace his lifetime of work. I was just then glimpsing why he said I would need my “courage of 10,000 men.”

That was at the beginning nine years ago. I returned to New Zealand every year and learned each new practice: Yuan Qigong methods to build physical health, Qi levels, and focus; still practices to develop energetic heart qualities; continual daily practices to develop a healthier consciousness and more. Along the way I uncovered the shaky foundation of my childhood; understood how people cannot give what they do not have; and learned how anger, drugs and alcohol can be used as an escape.

As a child, I chose a different escape to carry me through four decades: I buried the pain. I hid it beyond memory until the day my son’s teacher committed a small breach of trust. I felt the shaking start at my feet, work its way up through my legs, into my chest, and out my arms. A very old pattern of fear was emerging. Later when I replayed the scene in my mind, those words, “breach of trust,” unearthed the memory: not all school teachers are safe and not all adults are willing to see.

Two years later I dreamt of a dead body on the ocean floor, covered in silt with only a hand protruding. There was a gold ring on one finger. A red glow within the golden circle called to me. I wondered if I could go into the past and change things if I touched its centre. Instead, I awoke with excruciating chest pain – to me an indication that I was emphatically avoiding my dream’s message. After years of practice, I was now able to observe myself through some kinds of pain; there were no other signs of a heart attack. Still, decades of “safety first” training prompted me to rouse my husband so he could drive me to the hospital once I was able to move again.

As I sat in emergency, I maintained a loving heart practice. I focused on sensations of trust, openness, love, gratitude, and true respect. I was now calmer than the doldrums. I knew I would be okay if I stayed within my breathing heart.

The nurse said my vital signs were better than hers and my test results were fine.

On the drive home, I reflected on how I had used my practices to grow these heart qualities day after day and year after year. By cultivating them, my heart could now accommodate painful negative emotions. I knew that if I stayed present, my heart would hold me in love and compassion. I also realized I wasn’t brave enough to sit alone with the real cause of this morning’s pain. I was afraid of both the cause, and the pain itself if I continued to avoid it.

I requested help from a fellow practitioner, someone further along the path to realization than I. His presence helped me stay with my heart so I could safely explore more deeply.

His insight was that self-expression and love can co-exist.

My pain resurfaced, but this time instead of avoiding it I remained present, unearthing the root cause. My early childhood brain and heart had shut down my innate need for self-expression because I could not face the lack of love from those who told me, covertly and overtly, that I should not be heard.

“Stay in your playpen. Your curiosity and questions exhaust us.”

“No, we don’t have time to read your poem.”

“Mouth the words. Do not sing aloud.”

Becoming quiet and concealing pain had become survival tools. I gave up self-expression in favour of love. I had abandoned singing, writing, and anything creative and sealed it away in concrete. I swapped numbness for emotion, hid my inner spark, and traded vitality for an approval-seeking laugh and the dull grey mask of logic.

Self-abandonment was far more painful than anything inflicted by someone else.

This self-imposed restriction – that I could not be loved if I expressed myself – explained a lot about my life. It elucidated my fear of even private artistic endeavours. It explained my reactivity if my husband didn’t understand what I was saying. It unravelled why I froze in panic when I joined a music class in my forties.

But I went back to that class and learned to sing on stage. I spent years learning to be present for another’s pain, to speak what the rest of the group would not say, and to share my personal writing aloud. I devoted decades acquiring skills to stand up for my children, myself, and others.

Still, something blocked my heart’s doorway. After such an intense discovery and all the time spent healing the life that got me here, what more could there be?

I wanted the barrier to be a sheer curtain needing only a whisper to blow it away. I wanted it to be easier.

Some inner gift was still waiting for me on the other side. I could hear it say, “Go ahead. Greet yourself. Smile.”

Quebec, Canada, 2021

The pandemic has halted life for many. I’m in a red zone and have been under social, movement, and sanitary restrictions for nearly a year. All non-essential businesses are closed, curfew is 8 pm, and virtual gatherings offer the only human contact outside of my three family members. I’ve enrolled in an online writing retreat 5 000 km away in British Columbia. I am grateful to see faces without masks.

A First Nations Elder gives us our writing prompt. She beautifully describes the importance of ancestors, the land, and its history. She states that when people leave their homeland it’s like an evisceration. She guides us on an internal journey through a hallway, down a set of stairs, and into a clearing. Our forebears will be there to welcome us, encourage us, provide guidance, she says. She leaves us with our final instruction, “Without thinking, write down the message from your ancestors.”

I sit, my pen still. I don’t feel like my ancestors are restricted to my parents’ lineages. I have lived too many lifetimes for this to be accurate. I can’t grasp “evisceration” even though I feel the importance of relationship to land. I understand feeling at home in a place, but I’ve never felt at home in my place of birth. My world travels and openness to many cultures have given me a sense of being a global citizen. Borders have little meaning; we are all humans immersed in mucky histories in need of healing.

I wonder how this will go. The hallway I visualise is red like my heart. I go down the stairs, through the opening and into the clearing. I now see myself in a grassy area with a giant cedar. I realize the cedar is not just background, but my ancestor. This giant tree has lived on the Pacific coast for a thousand years. A mountain joins us. This is easy to see in my mind. I try evoking my grandparents. They smile, get fuzzy, then recede.

I see a dugout cedar canoe from the north. Some indistinct people move along the edges, but what holds my interest is the ancient navigator from the south standing with the canoe, even though the tree isn’t a palm and the vessel isn’t an outrigger. I have encountered this woman before. She is unique. It was Polynesian men who passed on the tradition of reading the waves, making stick charts, and voyaging into the unknown. This woman, Feminine Palu, holds her place with confidence. I don’t see her face, just her lean, muscular, competent body.

Now the scene frames a tiger. I walk across the grass and bury my face in her thick white fur. I have missed her. She hasn’t shown up in my nighttime dreams for some time. She has been angry with me when I wasn’t brave but she has also let me ride her into the ancient, mossy forest where women gathered. But this is not exactly a dream. She picks me up by the scruff of my neck, like a cub, and carries me to the cedar. Then I see them.

The dock bugs.

They are gleaming as they wander over the cedar roots above the grass. Thousands of legs march along the canoe from shade to sun. They don’t scurry or lurk. They turn my way. I open my arms and they parade across my chest. I embrace them, feeling warmth spread from my heart throughout my body. It is peaceful. Quiet. Serene.

I can love them.

I understand that what I truly love is my own greyness. The parts of me I did not like. The pain I hid so deeply that I had lost its memory for so long.

I understand that nine years of digging into my terror, shame, and grief have finally come to resolution. Hiding and avoiding no longer lurk. No more self-evisceration.

I can love the dock bugs. I can love me.