My 92-year-old Irish Protestant mother has been knocking on doors of almost every church in town, talking about unity and peace. She started with the Roman Catholics. “Do you know about the Doukhobors?” she asked Father Lawrence.

The Doukhobors, an ethnoreligious group, emerged in the late 1600s in the Caucasus Mountains of Russia. Originally called Ikonobortsy, those who reject icons, they did not believe the Bible was the supreme source of revelation and rejected the rituals and priesthood of the Orthodox Russian Church. In a gesture of insult, the tsar and priests labeled them “Dukhobory,” meaning Spirit Wrestlers, accusing them of opposing the Holy Spirit. The group embraced the term, interpreting it as a description of their struggle with and for the Spirit. They believed in personal revelation, where each person sought their own understanding of God.

“If you’d like to know more, I can put you in touch,” she says.

My father was a Doukhobor.

As a young man, my father hid his roots, scarred by schoolyard taunts like “Dirty Douk.” He overcame his shame as he got older. My brother and I weren’t raised in the culture, but like many parents, he eventually wanted us to know something about our heritage. When I was 14, he took us to a sobranie—a prayer meeting.

Men and boys stood on one side of the room, dressed in wool pants and roughly woven linen shirts. Mom and I were directed to the other side, where the women sat. A rainbow of pastel pleated skirts, matching long-sleeved tops with rows of covered buttons down the middle. And those embroidered, fringed shawls draped around their heads, pinned neatly under the chin. Mom wore one. I refused.

I was convinced the head coverings were meant to keep women hidden, modest, and chaste. I wanted to wear my own uniform: Doc Martens with black tights, a short skirt, and an oversized sweater. My parents talked to me about the importance of respect and tradition. I argued, “Tradition justifies patriarchy.” But Dad pointed out that an earlier leader of the Doukhobors was a woman, and said the Doukhobors believed in the equality of women.

“But only if they dress funny,” I retorted. I eventually relented, wore a modest dress, and sensible shoes.

The service was conducted in Russian, so I didn’t understand a thing. But I do remember the music. Doukhobor choral singing is haunting, solemn. The harmonies are complex, almost dissonant. The atmosphere created a strange sense of time warping. Over the years, I started to listen more closely, ask questions, and try to understand what this religion, culture, and way of life was really about.

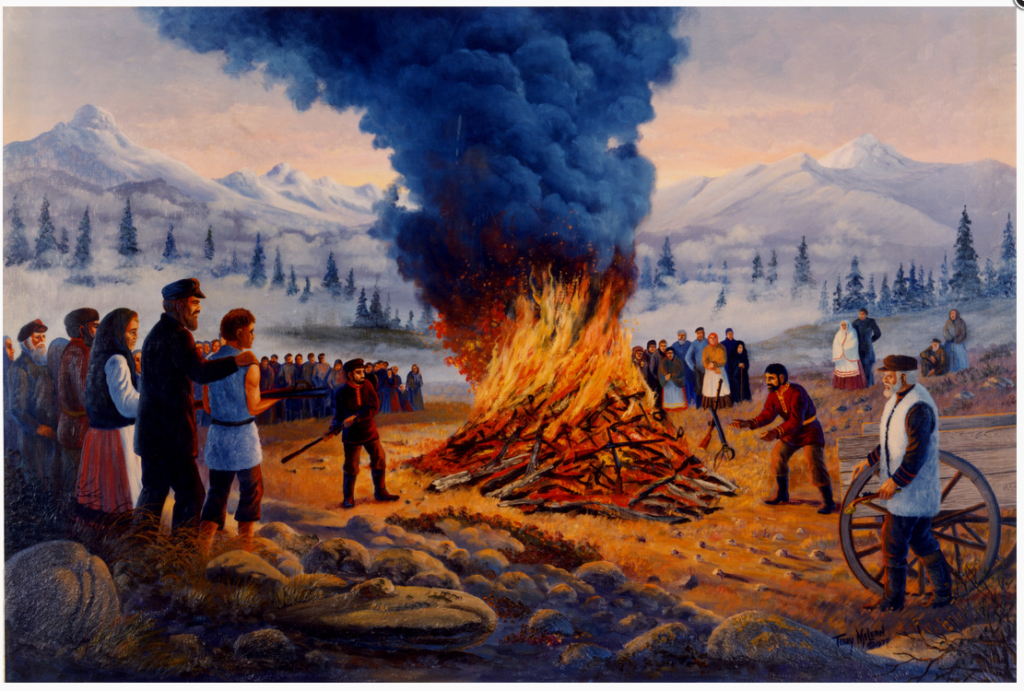

When Doukhobors greet one another, they bow, acknowledging the Spirit of God within. They believe that to kill another human being is to kill a spark of God. In 1895, Doukhobors in Russia gathered their weapons and set them on fire, refusing to fight in the war against Turkey. A painting of the Burning of the Arms hung in my grandparents’ living room, and I would gaze at the solemn faces of the men and women gathered around the flames.

In 1995, to mark the 100-year anniversary of the Burning of the Arms, a “Voices for Peace” choir was organized to spread the message of peace and nonviolence to parts of Canada, the United Nations, and Russia. Mom and Dad were part of that tour.

Dad has since passed, but my mother, in her later years, wants to spread their message of non-violence. A year ago, she attended the Anglican Church’s World Day of Prayer. The Presbyterian minister and Catholic priest shared prayers for Palestine and spoke about the refugees of all wars. The theme that year was, “I Beg You… Bear With One Another in Love.” When she came home, she wrote a letter to Iskra, the regional Doukhobor magazine, suggesting that like-minded pacifists gather together and “Do something!”

She only recently told me about these efforts. She is heartbroken by the invasion of Ukraine and the death toll in Gaza. “We should be out there marching and protesting. We should be out there promoting peace, all of us, together.”

I too watch in horror as genocide unfolds. But I am jaded.

“How would that help, Mom?”

“We have to stop this,” she retorts.

“How, Mom? How?”

“If all the church leaders preached pacifism, maybe the congregations would do something.”

“What congregations?” I ask. Most churches in this town have only a handful of parishioners.

Mom wrings her hands. “I don’t know,” she shouts. “But why do we think we can take what we want from other people, leaving them without what they want? War should be illegal. It should be illegal.”

I agree. But we both know many religions see war as a regrettable necessity, and even revere those who have laid down their lives “for their country.”

Recently, Mom has found a new way to bring different religions together. She hopes that if they meet one another, they might unite and become interested in working together. She is in good health but she is planning ahead. My brother and I have been informed that her funeral will take place at the Presbyterian Church and be led by an elder of the Doukhobor community. Her Anglican friend will sing a hymn, and the Lutheran minister and Roman Catholic priest will each be asked to say a prayer. When we deliver her eulogy, we will share her words and beliefs.

“The world would be a lot better if all refused to bear arms, as do the Doukhobors,” I will say. And collectively, we will respond, “Hear our prayer.”

We will follow her wishes, and we’ll add other details to her eulogy. We will speak of her vision for healing the world. And I will tell people I only recently realized the root of “Protestant” is to protest.

I don’t think it will make a difference. But neither does my inertia. Revolution always begins with some form of organized movement, incited by widespread popular anger at injustice.

Alex Ewashen, the author’s father, is in the back row, fourth in from the right.

(Images supplied by the author)