I saw her as I was climbing down one of the steepest mountain paths I’d ever been on. A rough stone niche held a picture of a woman, presumably the Virgin Mary. Some of her attributes were familiar: her blue robe, the rose held up in her right hand. Her left arm cradled a stolid, yellow-haired baby. Both mother and child were wearing crowns, rounded slats perched on their heads like empty birdcages. But in the middle of the woman’s forehead was something I’d never seen before in a picture of the Mother of God: a small, horizontal cut, dripping blood.

The painting was simple, even crude. The forms were flat, without nuance or shading. The woman’s eyes were aimed in slightly different directions, as if she wasn’t sure whether to focus on heaven or earth. The blood marking her forehead and throat did not flow in realistic streams, but appeared as discrete, iconic drops. They reminded me of the drops of blood that sometimes appear in fairy tales, staining pure white linen, to predict the birth of a princess or testify to old wrongs.

I paused in my downward scramble to stare at this mysterious presence, so serene and so wounded. Fruitful and bleeding. Could she be a different saint? Whoever she was, she inspired devotion; candles and flowers littered the shelf beneath her.

During the trailing months of the Covid pandemic, I was making my first visit to Ticino, the Italian part of Switzerland. With a week off from work, my husband and I had decided to be cautious and stay within the borders of our country of residence, rather than crossing over into Italy itself. I was disappointed not to be stretching our journey a bit further, but although Switzerland is a tiny and in some ways homogeneous country, it still holds surprises in its many hidden corners. Each region likes to lay claim to being a country of its own, with some justification.

I’m accustomed to walking in the mountains, for instance, but the mellow folds of the Jura range, where we live, had not prepared me for these knifelike ridges. Here, valleys were not open bowls lined with green for grazing cows, but wells of darkness, narrow, steep incisions carved by water flowing down the south side of the Alps. There was no such thing as going for a stroll to the next village; whenever we went out the door of our rented cottage, we were in for a strenuous climb, either up and then down, or down and then up.

No progress without suffering, this landscape seemed to be telling me. Maybe that was the same message my mysterious Mary had to offer. No birth without blood.

As I toiled up one slope during a day hike, winding through somber pines that blanketed me with their powdery scent, I felt exhaustion overcome me. We’d all been climbing for so long, and to what end? Where was the relief from this tension, this airlessness? I couldn’t see how we would ever reach a region of more light and freedom.

I remembered a mindfulness practice I’d recently encountered. Go into the sensation, even into pain, don’t resist it. Feel your feet on the ground, each step meeting the earth anew, a constant source of surprise. Let your thoughts go. Don’t get caught in them, but don’t resist them, either. Another way of being might arise, but only when you lose your panicked grasping after future phantoms, and stay with the present moment.

When I got out of my tumble of anxious thoughts, and into my feet, the way upward became easy. My husband was startled by my sudden access of energy. Soon we were above the dark trees, looking toward a new horizon.

I never did learn the story behind the Madonna of the Wounded Brow, but her picture became part of what I took home from this brief journey. She reminds me that while our heads may suffer many wounds, even those that never heal can’t stop us from finding our way.

And whatever happens, don’t neglect to put on your crown.

~

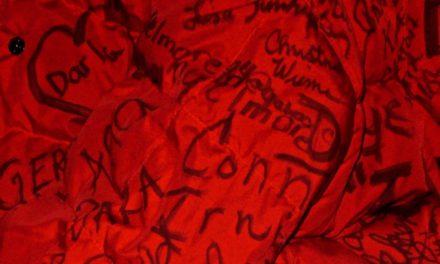

All images by Lory Widmer Hess