About the

Braided Way Symbol

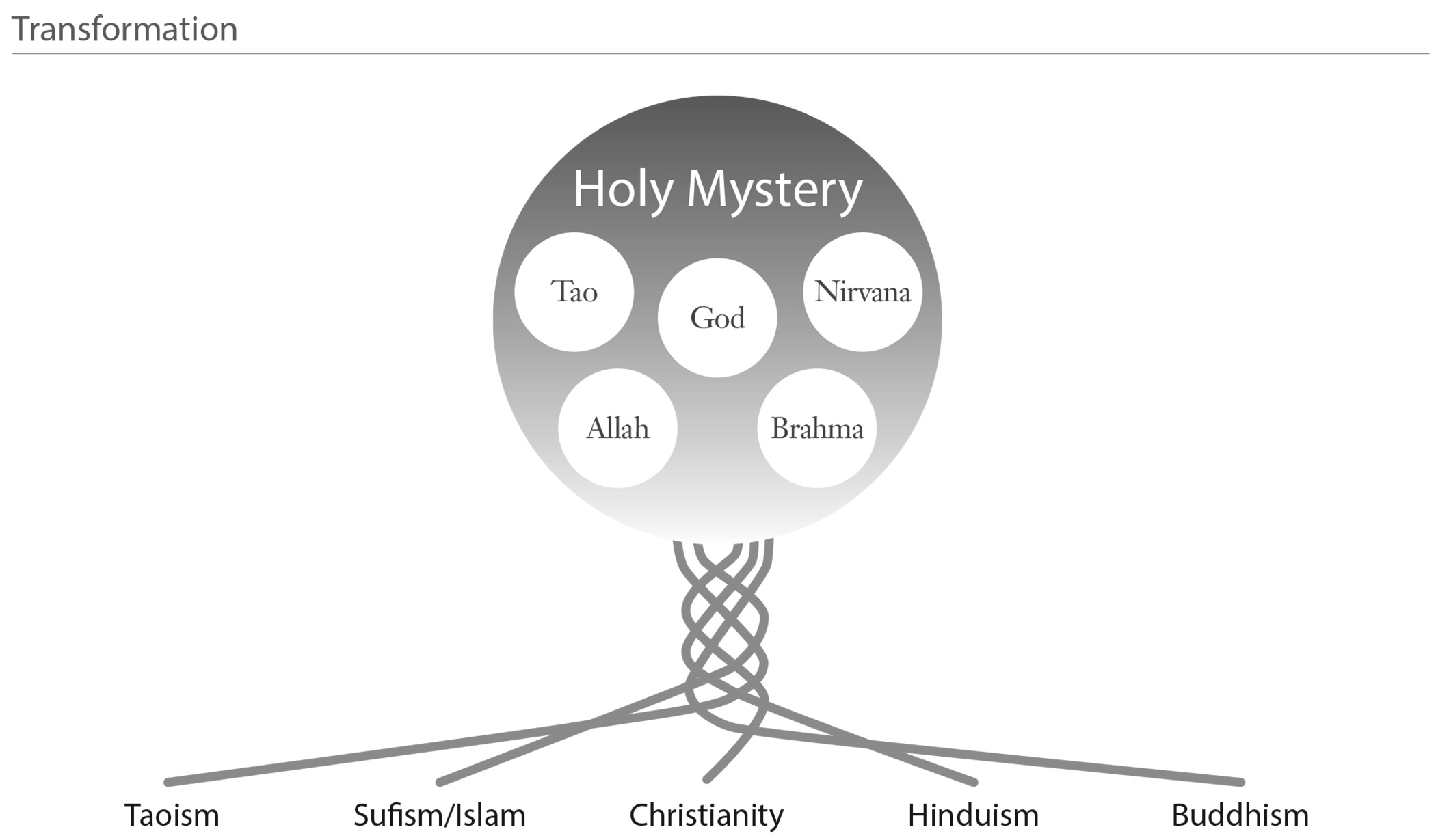

The Braided Way is an approach to spiritual development, which allows us to integrate faith traditions, while honoring each faith’s unique contribution to the human awareness of the Holy. In the Braided Way, each faith tradition is a strand that intertwines with the other faith traditions, forming a braid, which contributes to our awareness of the Holy Mystery.

The Braided Way does not present all faiths blending into a single, thick strand. Rather, the image of the braid compels us to value each individual strand in its unique, cultural depth and heritage.

What is important in the Braided Way is the ability to choose spiritual disciplines from various faith traditions. There is no prescribed combination. A person raised Christian may decide to supplement his faith tradition with Native American ceremonies, which celebrate the Earth. A person without a tie to a faith tradition can approach the braid, searching for the spiritual discipline, which speaks to her intuitive connection to the Holy. A vivid dream life may draw her toward prophetic practices in the Kabbalah; warm hands in prayer may lead her toward studying Reike; a desire for the calm of meditation may reveal a need for Buddhist practices. What is important is to respect and explore the deep, historic roots of each of these strands in the braid of spiritual experience. There are far too many books and spiritual teachers among us who are claiming to offer a “new” spiritual path, only to present a superficial and non-historical re-packaging of the ancient traditions. It is important in the Braided Way to acknowledge the deep historical roots of our world traditions.

A major criticism of this eclectic approach to developing spiritual awareness is that it does not allow for the life-time commitment and depth of a single tradition. People often claim that instead of digging one deep hole of spiritual development, people seeking a braided path will instead dig many shallow holes. However, the writer Debra Leigh Scott counters with the argument that she is indeed digging one deep whole of spiritual growth, she is simply willing to use a variety of tools. A more crucial question is: what is the goal of the hole?

When entering the Braided Way it is important to accept that the universal goal of spiritual living is to seek unity with the Holy. All of the mystical traditions in our world faiths rose from the unitive experience of their founders. At base, what unifies these traditions is a goal to what many call “unity consciousness.” In Theistic traditions, this goal is characterized by a desire to be in divine union with the Creator. In traditions such as Buddhism and Taoism, this unity experience is described as expanded consciousness. In both cases, the mystical journey entails an awareness of non-duality between the self and the universal. This sacred awareness of the interconnection of all things—of the union between the internal and the external, of the merging with the great mystery of the universe—is the foundation of the Braided Way because it is the natural origin of all mystical traditions. The unitive experience is described in different ways, understood in different frameworks, expressed in different languages, encouraged in different rituals, but it is fundamental to the mystical journey. The Braided Way is an invitation to a sacred path of interspiritual mystical experience.

The Braided Way Symbol

-by Michael Olin-Hitt

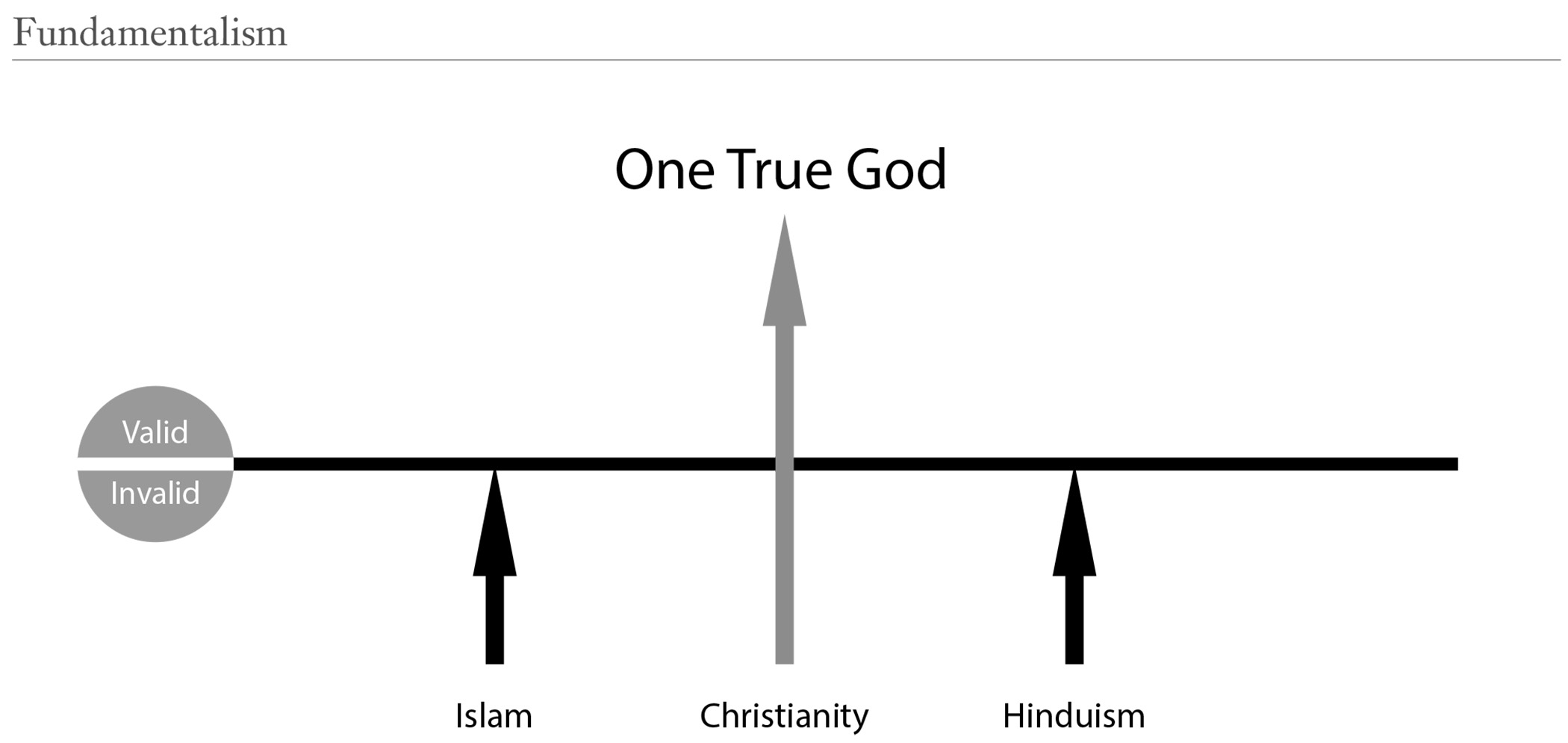

In order to further explain the Braided Way, it will be helpful to review a few of the common approaches of understanding the relationships of world faiths. I will begin with fundamentalism, which is the most harmful, exclusive and intolerant form of religious perspective.

-

Fundamentalism:

Fundamentalism is present in many religions, but the Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam are particularly vulnerable to fundamentalism because of the biblical promise God makes to Abraham to build a nation of chosen people. Fundamentalism is a perspective, which privileges one faith as the only true and real faith and one faith story as the only valid and true human narrative. Even within faiths, there are fundamentalists in sects who reject other forms of their faith, such as the religious right in Christianity as opposed to socially liberal Christians, or the Suni in Islam as opposed to the Shi’a. Fundamentalism is seen not only in regard to religion, but also to political systems. Indeed, many people are as intolerant of other political systems or political parties as they are to other faiths. Often, fundamentalists link their political views with their religious views, leading to strict dogma and intolerance. Fundamentalism is arguably the most destructive element of human culture, which has led to countless social clashes and wars, some lasting for generations. As the writer and Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh has written, “When we believe that ours is the only faith that contains truth, violence and suffering will surely be the result” (2).

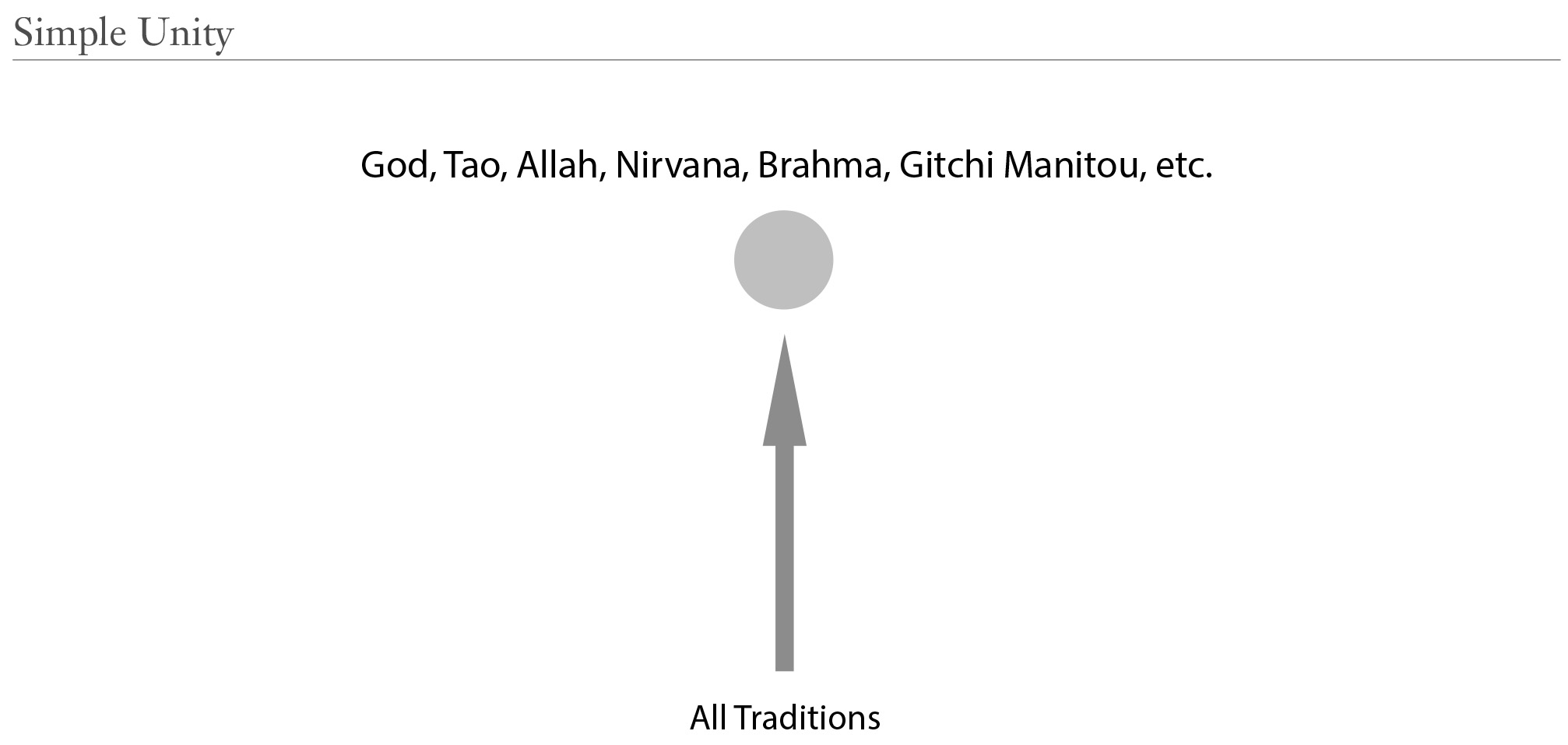

While fundamentalism views only one faith as having access to God, in the approach I call “simple unity” all religions are viewed as leading to the same God. People who hold this view are tolerant of religious diversity, but ultimately not interested in the wondrous and unique differences between the wisdom traditions.

2. Simple Unity:

In the simple unity of religions, it is assumed that there is only one path to one understanding of God. The different traditions are merely the result of different cultural understandings of the same goal. Often, people who hold this simple idea of unity are closer to fundamentalism than they realize. Such people will often reduce all religions to validate their own concept of God. A person holding this simplistic view of world religions will often acknowledge other faiths, but may have limited tolerance for different concepts of God or ultimate reality.

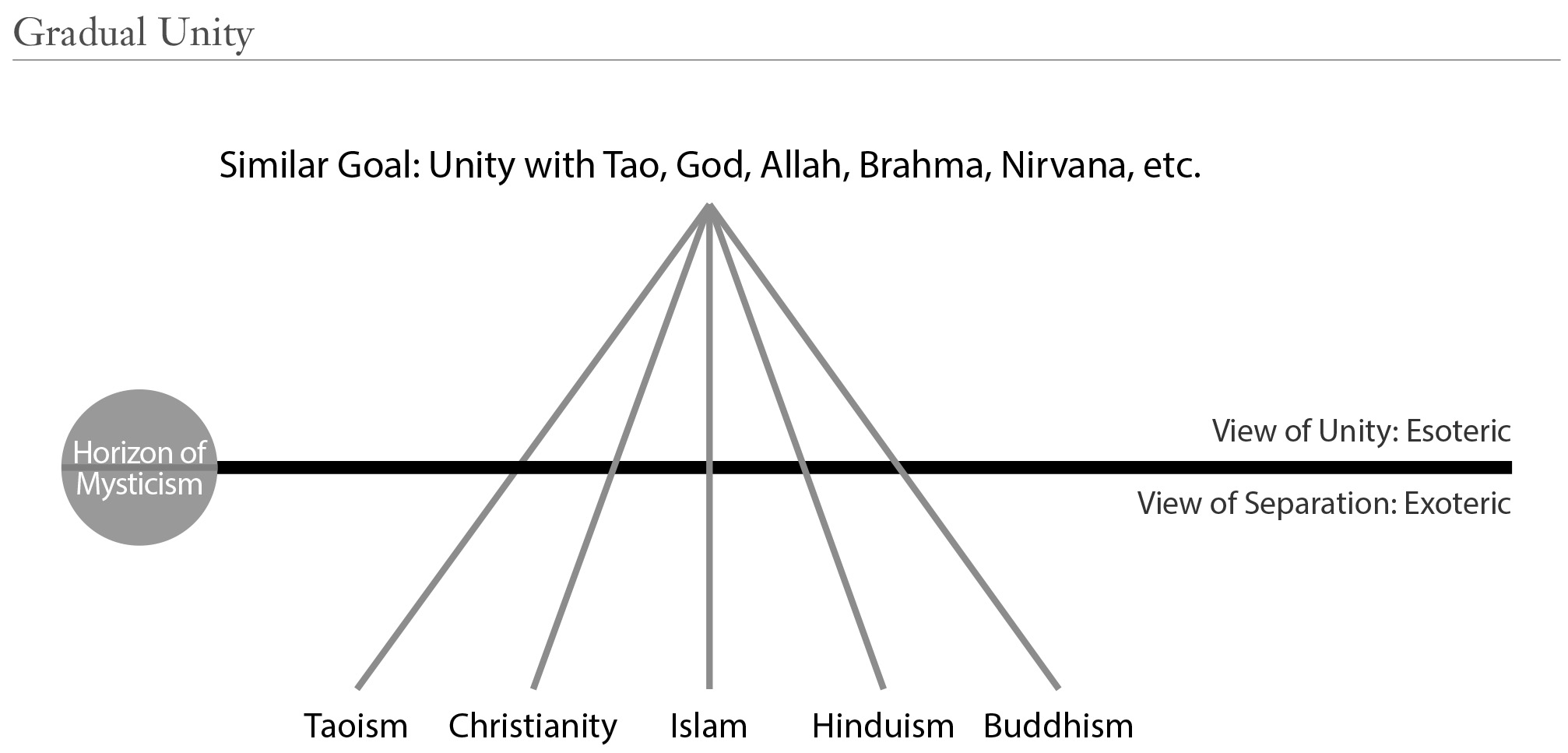

3. Gradual Unity

In a third approach I call “gradual unity” people within the faith traditions begin to see that the many faiths ultimately lead practitioners to a sense of unity with the Holy. Often, this understanding that faith traditions lead to a similar merging with the Sacred is realized by those who have had mystical experiences of their own. In these mystical moments of blending with the Holy, an awareness of a larger reality often comes upon people, after which the divisions between faiths become less of a barrier to a common sacred experience. People who have progressed into the mystical arena in their faith journeys are no longer threatened by the cultural differences represented by the faith traditions and instead become engaged with the unitive nature of mystical awareness. I was introduced to this diagram in Frithjof Schuon’s book The Transcendent Unity of Religions, first published in 1957.

Schuon used the term “exoteric” to describe people who cannot entertain the unity of faiths and “esoteric” to describe those who can. I have taken the dividing line between the exoteric and esoteric and renamed it the “horizon of mysticism,” which indicates the level of spiritual development of those within a faith tradition. Above this horizon, the goal of unity with the Holy becomes emphasized over the differences of faith traditions (Schuan’s esoterics). However, below this level of spiritual development, people within the faith traditions are not able to see or understand the possibility of the common spiritual goal of the various world faiths (Schuan’s exoterics). Such people prefer to see their faith as distinct from other faiths.

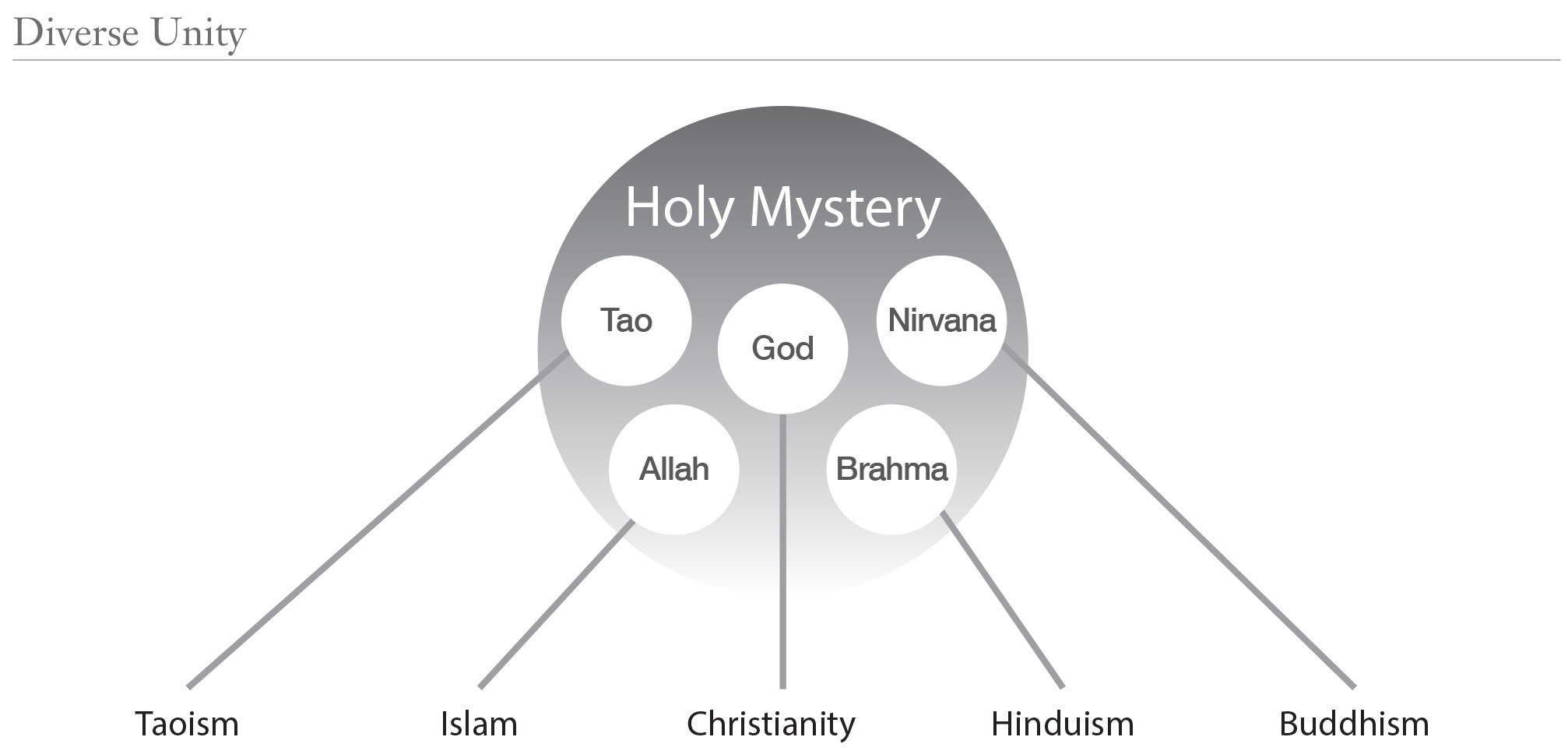

While the model of “gradual unity” allows the spiritual seeker to see the validity of all faith traditions, it limits the incomprehensible nature of the Holy Mystery. What I mean by this is that the model presents all the different faiths as leading to the same goal, which is merging with the Holy. In the next model, this mystical merging with the Holy is understood as being different for each faith or even each practitioner of each faith. In the model I call “Diverse Unity,” each faith tradition leads to a unique experience or manifestation of the Holy Mystery. I first ran across this diagram in Jorge Ferrer’s book Revisioning Transpersonal Theory.

4. Diverse Unity

This model allows people to recognize that the Buddhist’s experience of nirvana is different from the Christian’s experience of contemplative prayer. However, while different, these experiences are equally within the wholeness of the Sacred. In other words, the Holy Whole is so vast that it contains, allows for, and invites diverse experiences for the human spirit. This approach leads to an understanding that the many paths lead to unique but equally valid experiences of the Universal Spirit. The approach also allows us to acknowledge that the wholeness of the Sacred is too vast for any single faith tradition to fully represent.

For many, this approach to inter-religious understanding has offered the freedom to view all faiths as equally valid while allowing for a complex unity of the Holy Mystery. However, this diagram presents the various faith traditions as separate, denying the ability for interspiritual experience, in which each faith tradition influences the others in our global interdependence.

In order to present the Braided Way, I will gradually alter the “diverse unity” model, portion by portion. First of all, the Braided Way allows us to acknowledge that the faith traditions are not as independent from each other as they appear. Historically, many of the faith traditions have evolved from other faith traditions. For instance, Christianity came about through the Jewish tradition because of the radical teachings of Jesus, and Islam also came from Jewish roots through the prophecies of Mohamed. The dualism of Zoroastrianism is often credited with the development of the Judeo/Christian understandings of good and evil. Buddhism is the result of Siddhartha Gatama’s reactions against Hinduism. Taoism’s spiritual writings came out of China during the rise of the very non-spiritual Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism is the result of the blending of Taoism and Buddhism. Many of the Native American traditions evolved into separate traditions as groups migrated and deviated. In addition, other blendings of faith traditions have taken place during imperialistic take-overs, creating a wide variety of subdivisions in each major religion.

To represent the inter-relationality of the faith traditions, I will intertwine the lines from the faith tradition to the Holy Mystery. In doing this, the diagram begins to take the shape of the tree of life, as represented in Celtic art. It is appropriate for the tree of life to emerge in the formation of the Braided Way, for the concept of the tree of life or the sacred tree is seen in various traditions, including Judaism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Celtic spirituality, and Native American traditions. For the purposes of the Braided Way, the tree of life represents the life of our faith traditions. Our faith traditions are only valid paths if they are lived, and the faiths themselves change and grow as we live them.

In taking the independent lines of the faith traditions in my diverse unity model and braiding them, we are able to represent the way our many faith traditions influence one another. Let me also stress that our faith traditions rely on each other. If the Holy Mystery is too sweeping for any single faith tradition to represent, then it is only in the combination of faith traditions that we can come to a more complete understanding of the Holy. If we reject or ignore the strand of any faith tradition, we also weaken the entire braid.

Next, I have to altar the representation of the Holy Mystery in the diverse unity model. In our current model, the Holy Mystery is a goal to which the faith traditions lead, represented by the circle. To complete our transition from the diverse unity model to the Braided Way, I will broaden the circle of the Holy Whole to encircle and encompass the tree of life.

The Braided Way

In the Braided Way, our spiritual life is not a journey to a goal. The many paths do not lead us from our present life to a separate spiritual or heavenly life. Instead, the Holy Whole is continually surrounding us and is revealed in our every-day lives. The very act of walking our spiritual journeys allows us to participate within the dynamic and continual braiding of the Sacred. Nothing is outside of the Sacred. Nothing leads to the ending destination of salvation. The Holy Whole is everywhere and we continually participate in the Holy Mystery at every stage of existence.

The circle of the Braided Way represents the continual, creative presence of the Sacred. For this outer braid, I have borrowed the Celtic knot, which is a braiding with no beginning and no end. This outer braid is not separate from the inner braids, but it encircles and incorporates the other braids. In the Holy Mystery, the many become the One.

The Braided Way is both a metaphor and a conceptual framework to facilitate our movement into the interspiritual age. In the braided image, we seek inter-faith sacred experience, which takes us beyond inter-faith dialogue. Whereas inter-faith dialogue promotes discussions, which seek understanding of “otherness,” inter-faith experience brings people to an awareness of spiritual and human “sameness.” In inter-faith sacred experience, people of different faith backgrounds can enter into ritual together, sharing in the experience. However, with different perspectives, each individual will have a unique view of the ritual, allowing for depth of sharing. This inter-faith experience is the core of Wayne Teasdale’s presentation of the term “interspirituality.”

Finally, as the braid twists upon itself, it becomes difficult to differentiate the strands. A single strand cannot be followed beyond the first braid. Instead, the strands become intertwined—blended into the pattern of the braid itself.

Although I do not suggest a list of characteristics or requirements to define the Braided Way, I can make some predictions of what will be the results of practicing the Braided Way, and I am convinced that these results will address the major political, social and ecological issues of our generation. As Johnson and Ord properly describe in their book The Coming Interspiritual Age, the goal of interspirituality is to bring unity consciousness: “In the context of religion, interspirituality is the common heritage of humankind’s spiritual wisdom and in the sharing of wisdom resources across traditions. In terms of our developing human consciousness, interspirituality is the movement of all these discussions toward the experience of profound interconnectedness, unity consciousness, and oneness” (9).

Because unity consciousness or the merging with the Holy is the primary goal of the Braided Way (and the interspiritual philosophy), it is possible to imagine several characteristics or “fruits of the Spirit” to naturally arise. I will name just a few: Compassion for all living creatures, acceptance of diversity, spiritual connection to the natural world, commitment to peace, patience with ambiguity, commitment to social justice, and finally the exploration of spiritual experience through various rituals and practices.

Other characteristics or spiritual fruits could also be named as a natural development of the Braided Way, but any list would be finally reductive and incomplete. In short, the Braided Way allows for human consciousness to expand in an embrace of unity in multiplicity. The unitive experience with the Holy, regardless of the religious tradition, yields a deep conviction of interdependence and relationality. Johnson and Ord explain that interspirituality is “the way authentic spirituality has inherently responded to humankind’s advancing sense of unity and inevitable process of globalization and multiculturalism” (362). The Braided Way provides a common goal (unity consciousness) and a structure (the braid itself) to the interspiritual movement that is gaining momentum in our contemporary search for ultimate, unifying meaning.