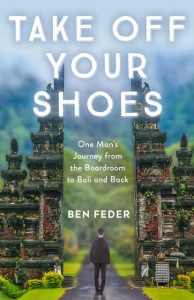

When CEO Ben Feder realized his high-performance business life was seriously impacting his personal and family health, he made what could have been a career-ending decision to travel with his family to Bali for an eight-month sabbatical. This corporate leader’s path to self-discovery went around the trappings of religion and instead leaned toward outcomes. We catch up with him as he begins to learn meditation in an excerpt from his book, Take Off Your Shoes.

One evening, I made my way to Yoga Barn for their evening Tibetan Singing Bowl Meditation class. I arrived ten minutes early to secure a spot, removed my shoes, and walked into the same studio in which Victoria and I practiced power yoga. Instead of Denise standing in the front of the room, Swami Arun sat there cross-legged and dressed entirely in white. His hair was a Medusa’s tangle of long dreadlocks tied at the crown of his head so that they sprouted like a large shock of crabgrass. In a semicircle before him, he placed about a dozen metallic bowls of various sizes.

Arun asked the participants to grab yoga mats and lie on their backs in a semicircle in front of him, heads toward the center. He picked up a mallet in each hand and tapped either side of the bowls, creating a soft gong-like sound. Then he repeated that for the other bowls, producing a symphony of reverberating gongs. By rubbing the mallet around the outside edge of the rim of the bowl, he created a high-pitched harmonic sound. Arun stood, holding a small cushion in his hands, on top of which he placed a midsized bowl. He brought the singing bowl around the room. When he came to me, he placed it first next to my right ear and then the left.

There was no particular melody to the sounds of the bowls, but I found them deeply relaxing. Arun asked us to close our eyes as he continued to work the singing bowls, creating a symphony of vibration, an invitation to let go of my thoughts and succumb to relaxation. I remembered the instruction I had received at the ashram and tried to be aware of my thoughts, tried to watch them, almost clinically, as if they were secretions of my mind. But the room was dark, I was lying at on my back, and Arun’s voice was too soothing. Within minutes, I was fast asleep.

I awoke after about twenty minutes to the sound of a large gong. The other people in the class had fallen asleep too and were now stirring. I pushed myself up from the floor, crossed my legs, and sat a few minutes longer. Then I bowed my head as instructed and stumbled out of the room in a semislumber.

On my motorbike headed home, I grew concerned that meditation in Bali was inaccessible for someone like me. Where was the peace of meditation without the weirdness? Where was I supposed to connect with the wisdom of meditation without succumbing to swamis, ashrams, and religious experiences?

By the time I powered down my bike in front of our home, I abandoned the idea of taking classes or learning from a teacher. Instead, I decided to turn to established experts. That approach had seemed to work for me many times before both personally and professionally. Thankfully and ironically, they were easily available on one of those electronic devices from which I had sought sanctuary, the Kindle.

Our home was one of the lucky few with a consistent if slow Wi-Fi connection, and I downloaded volume after volume, looking for pointers on various meditation practices. The first was the most impactful. Joyful Wisdom was written by a Buddhist monk with a light touch and a sense of humor. He’d been born with what would later be labeled severe anxiety disorder, which he overcame through meditation. I went on to read everything by Jon Kabat-Zinn, Dan Siegel, and Richard Davidson. Sitting uncomfortably cross-legged on cushions, I listened to guided meditation podcasts by Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzberg.

Through research, I learned that mindfulness meditation was not prayer. There was no deity, no praise, honor, or supplication. There was neither asking for help nor seeking answers. Meditation was prayer’s opposite. It taught the practitioner simply to be, without praise or judgment.

Nor was meditation relaxing in the way that, for example, a massage was relaxing. Meditation required concentration. It required an upright spine and alertness. Letting the mind drift off in a relaxed state defeated the purpose. And yet, as a result of focused attention, the end of a meditation practice resulted in a refreshed sensation.

I learned that to sit in silence alone with my thoughts was to observe them dispassionately and nonreactively. As thoughts came and went, there was an infinitesimal moment between them, like the space between frames in an old movie reel or the frames in a graphic novel. That empty, miniscule instant between one thought and the next was a tiny, quiet moment of peace. My aim was to stretch that empty space, to slow down transitions of thoughts so that the in-between bits were more pronounced, less like the space between fast-moving movie frames and more like the turning of a page in a book. The goal of meditation was not to empty my mind of thoughts—that would be impossible— but to be so aware of them that I could experience fully the space between them. It was a gigantic goal, and I accepted that it was likely to be an aspirational one that could easily be pursued over a lifetime.

I learned too that in meditation, as in many other situations, failure is unavoidable. While the basic technique of meditation is focusing attention on the breath, inevitably attention wanders to any number of distractions. And when it does, attention breaks down. In that way, meditation was an exercise in failure. But failure fed recovery, and the recovery in meditation was both easy and constructive. The critical moment came in the instant of recognizing the wandering mind and bringing attention back to the breath and refocusing. Meditation was a cycle of losing and regaining attention, of failure and recovery.

In one of my early sessions, I learned a lesson for the businessperson, more than just the old saw that failure is part of the process. Thoughts of past failures and missed goals kept intruding into my mind. I got caught up in the first two or three digressions but was able to quickly refocus on my breath, and I felt stronger. I realized, without dwelling in it, that each of those “failures” had led to recovery and each recovery to strength. Later I read that Carol Dweck, the Stanford psychologist, had discovered that the entrepreneur or professional who does not accept failure as an inevitable outcome of trying and learning, who adopts an attitude of judgment and criticism or labels career experiences as either failures or successes, is less likely to recover, develop, and grow. For that person, failure is an unacceptable outcome from which recovery is not a learning experience. Failure is a sin from which redemption can only be wrought through yet more success. Whether failure translates to a growth experience often depends on one’s frame of mind.

I thought back to my decision to take a break from my career and how concerned I was that some might have construed it as failure. I needed to remind myself that I had voluntarily walked away from my job and possibly from some close relationships that were deeply important to me. In meditation, I cultivated a mindset that did not require my attachment to success. I needed to do the hard work of changing the wiring of my mind, of noticing when I felt like a failure and shifting my thoughts, if only slightly, to construct a different narrative, one that included a sense of growth, discovery, and new experience.

An underlying aspect of meditation gradually became more and more clear to me. It’s a practice, not a single event. My experience at the ashram was set up to fail. It was impossible to have a meaningful experience, religious or otherwise, simply sitting with eyes closed, listening to a man in a sarong playing the sitar. What was required was a dedication to sit daily, if only for a few minutes, with the intention of being still with my thoughts. It could take years of daily practice for meditation to have its effect. The brain does not change overnight. The investment in meditation was not a few minutes. It was a few minutes each day for many, many days over months and years. Meditation was like an insurance policy, small premiums paid regularly over a long time that brought both a little peace of mind and, in the event of a crisis, a lot of help, even salvation.

I started a daily practice. It was a struggle, but I kept it up. Someday, I thought, I might need to harvest my investment.

Excerpt from Take Off Your Shoes: One Man’s Journey from the Boardroom to Bali and Back by Ben Feder, used with permission from Ben Feder, © 2018