Playful lessons on living from the oh-so-observant wise man, Bernie DeKoven.

I think it’s been happening ever since Babylon. And once we got to America, it’s been really happening. Each of us has somehow decided that Judaism is something we can make up as we go along.

Not completely, mind you. Certainly not from scratch. But we do have that certain itch for making Judaism, well, shall we say “relevant.” And we do feel that we have a certain right to decide on our own just how relevant to make it.

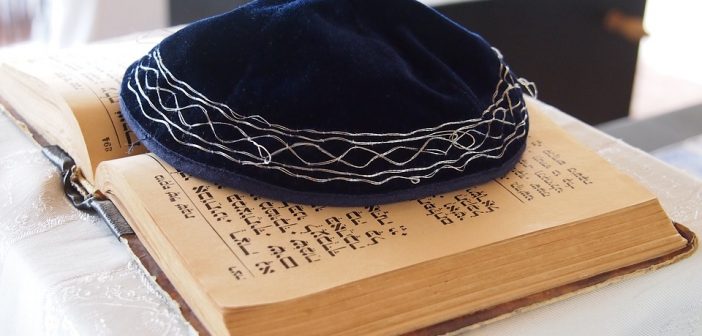

We have our Rabbis and teachers and traditions and books, thank Something, but for many of us the god thing seems a little too far, shall we say, out. Even those of us who grew up observant – after we leave home, and maybe don’t go to Shul so much any more – ultimately decide that we have the right, if not the commandment, to be Jewish in our own particular, not necessarily kosher, if you know what I mean, way.

I, for one, despite being the son of a Rabbi and Rebbetzin (wife of a Rabbi), aleyhem hashalom (peace to them), grew up into what I’ve come to understand as a Paradox Jew. For a long while, a very long while, even though I davened, laid tefelin (phylacteries, and shokled (bowed back and forth), and prayed with all my heart and soul and might to HaShem (lit. “the name”), ultimately I grew less and less certain as to Whom I was praying, and why and what for. I became a vegetarian and decided that was Kosher enough. I made up my own prayers and decided that was religious enough. My home was my shul. My wife my chazzan. We lit candles. But our Shabbosim (sabbaths) became more and more a day of communion with the spirit that had grown between us. Not God’s. But ours. The divine We.

One day I was talking to someone, an old business connection, and I mentioned Shabbos to her, and she said “Jewish? You’re Jewish? I never would have guessed.”

And on that day, or maybe a little later, I decided that I needed to reclaim my Jew. That maybe I my homegrown Judaism had gotten a little overgrown, and I once again needed to reinvent my religion.

Because, see, I really felt that Judaism is my religion. A Jew I have always been. But religious, I guess it depends on what you mean.

So I started with the things that meant the most to me – Jewish-like things: traditions, customs that connected me back to the wise and weary soul of my people.

One of those things: brachos. You know, after years of saying a blessing every time you take a bite of something, or see a rainbow or come out of the bathroom, and then you, well, lapse – you miss it, this thanking thing, this quiet pause, this moment of appreciation for the gift of life itself.

But it’s hard to make a blessing when you’re not sure the word “god” means anything real enough for you to actually thank.

Though we’re vegetarians, mostly, every now and then we eat a piece of fish – because, you know, it jails our free radicals or something. And there it is on our plates, this piece of a beautiful, powerful animal. And we have to say something. So we started saying “Thank you, Fish.” And that was pretty much as far as we got.

Most recently, though, I’ve been thinking of saying “planet” or “earth.” I’m going to try it out on easy things. Like when someone sneezes, maybe I’ll say “Earth bless you.” Or when something happens to me that didn’t kill me maybe I’ll try saying: “Thank you, planet.” Maybe that’ll get me closer. Because it’s part of me, this gratitude impulse, that I inherited, that I value, and, as a Jew, and as a me, I don’t want to let go.

And there are Jewish teachings that I want to remember better: like things about compassion, about not judging people until you really understand their circumstances. There’s a saying, a Jewish saying I remember that goes something like “dan l’kaf zechus.” Which has something to do with giving people the benefit of a doubt, or even better, “assuming positive intent.” This was a teaching that touched my wife very deeply. And, in passing, she one day told me a story of how she plays a game of dan l’kaf zechus when she’s driving. It goes like this:

If someone cuts in front of her, for example, or blows their horn (well, actually their car’s horn) at her, instead of getting angry, she tries to think of all the possible reasons for that person being so ungodly rude, so to speak. Like maybe he’s on his way to the hospital for some kind of emergency. And not only that, but his kids don’t have a ride home from school. And even worse, he has to go to the bathroom. Or maybe he’s trying to make way for the car behind him, because someone in that car is violently ill.

And on and on she goes, thinking up excuse after excuse, plausibility after semi-plausibility, until the anger fades and is replaced by a quiet sense of fun, and maybe even sanity.

No one ever said the life of a homegrown Jew would be easy or even better, but it’s good to know we can do such things, even though we’re not doing what the rabbonim might want from us. We can take the sensibilities that we’ve inherited, we can honor our parents and theirs, we can be our own best kind of Jew.

I’ve been trying it out, thanking the planet for my food and stuff – though my sacred wife still wants to thank the fish personally. I’ve been not so much trying it out as thinking about trying it out – especially about the planet-God connection. I don’t know how kosher it is to thank the planet. It’s not exactly idolatry. And it’s hard enough thinking about the planet – the whole planet – as one single thing, something I could personally thank for anything. Now that I’ve seen pictures of it from space, I can imagine it as just one thing, small, huggable even, compared to some of its neighbors. I can even think of it as a living being because this is where I find my life and all the lives I encounter. But to think of it as listening to me, as appreciating my gratitude, as something like God, as even wanting my gratitude… I might as well thank a dead fish.

No, it doesn’t seem to work for me, thanking the planet, or praying to it either. I can love it, though. I can’t hold it in my imagined embrace but I can appreciate it’s beauty, it’s complexity, it’s life-givingness.

There’s a thing my particular people call Tikkun Olam. It means to repair the world. As a practice, even picking up a piece of litter is Tikkun Olam. Or reusing a plastic bag, or repurposing, or conserving energy, or planting a garden, or designing a little toy or game or playground that makes things a little more fun. And so is visiting the sick, bringing a nice nosh at a shiva, celebrating life events with family, community and strangers. Traditionally, it is all a Mitzvah – a commandment, a good thing to do, holy even, just in the doing. It’s what I might call “active prayer.” Like celebrating, serving, enriching, healing, loving. So if there were such a thing as a Planetary Jew, that’s the kind of thing we’d be doing a lot of.

Jew? you ask. Call this Jewish? you scoff.

Well, see, I have to approach my planet as a Jew would, because, that’s me, Jewish, by birth, by blood. Judaism is in the DNA of my spiritual genetics. And if I were a Christian, I would have to approach it as a Christian would; a Buddhist, a Muslim, Hindu, Taoist…as they would. And yet, no matter through what lens we see it all, we would all be worshipping together. Despite our differences, we’re all on the same planet, if you know what I mean.

And then there’s a mitzvah called Bal Taschit – another commandment which says, basically, Agent Orange is not Kosher. Don’t destroy what you don’t have to. In fact, don’t destroy unless you have absolutely no alternative. Which extends to the whole plant, naturally; as in conservation of life, of the planet.

And Tzedakah, which has something to do with being just and charitable and that, too, can be extended to all life.

And even more important: Gemilut Hasadim – the “gift of loving kindness.” All commandments, straight from the hand of God and the heart of the planet.

As a Jewish, um, Planetarian, some of the books included in my conceptual Talmud would be written by the poets and authors and artists and scientists whose works enrich my understanding of the world, widen and deepen my embrace of the whole of family, the whole of community, of humanity, of life, of the planet I live in and serve. Other books by geologists, geographers, geophysicists, ecologists, hydrologists, physicists, biologists, astronomers, cosmologists – the legions of researchers, experimenters, explorers, scholars who help me perceive the world more clearly, perceive the whole of it. Still others by playwrights, musicians, dancers, artists who help me love it more deeply, more widely. Players, lovers, children, mystics who help me open my soul to it.

As a Jewish Planetarian, it would be my biggest mitzvah to love the world completely, with all my heart and mind and soul. And to fulfill that mitzvah, I’d need to begin with the things and beings I already love so I can learn love from them.

I learn about life from living. I learn from the seasons to celebrate the seasons, from the phases of the moon to celebrate the year, from the sunrise and sunset, the minor miracles of a cool breeze on a clear day, of the rain, and the end of the rain, the change, the variety, the all, the glorious, incomprehensible all of it all.

I learn about love from loving. Forty-nine years with my wife, my primary teacher, and I’m still learning love. Learning to love the children our love brought to us, and the children their love brought to them. Learning that it is impossible to love her so completely without loving everyone that loves her, everyone she loves, who brings her life, that sustains her, inspires her, appreciates her, helps her find meaning, heals her, makes her whole. Learning what love means. Learning how to bring it into the world. Learning how it can possibly become large enough to embrace all of her, and our children, and theirs, and the communities that sustain them, and the planet that sustains us all.

Bernie & Rocky DeKoven