After the death of a writer friend, I attended her memorial service at the edge of Steamboat Lake not far from where I live. The presiding pastor, dressed in a red plaid western shirt and black Wranglers, wore his long gray hair in a ponytail. With a brisk September wind to his back and with kind assurance, he ended his blessing with, “Her spirit is now a footprint in the snow, an echo in the mountain whenever she’s near.”

Sarah, a tall, elegant and athletic blond in her fifties, lost a fierce six- month battle with cancer and told no one until the last six weeks of her life. I found comfort in the pastor’s words. Still struggling with the finality of my mother’s death earlier in the year, the notion of her spirit “an echo in the mountain” drew me in.

At ninety-four, my once hearty mother dies on a cold January night. The wind blows, ice forms on windowpanes and sidewalks. After her last labored breath, my sister and I call the funeral home. In the darkened hallway, I thought I’d walked into the wrong movie when Jerry, the tall funeral director, dressed in a long, black overcoat, arrives with his gurney furnished with a red plush blanket.

During the last week of her life we hold close vigil over her: playing her favorite hymns, rubbing her hands and face with lotion, and welcoming friends, family and Pastor John who softly chants Christian blessings at her bedside. When death comes, my sister and I spend a few moments with her after the nurses’ aides gently straighten her up, supporting her head with a towel so we can remember her, not a crumpled body on its side, but as our mother, dignified in death.

After formalities with Jerry, my sister and I gather our mother’s Bible, a vase of still-fresh flowers, curl up in our coats, walk through the back door of Fair Acres Manor and down an icy sidewalk slope to my car. Jerry escorts my mother through the front door on the mortuary’s gurney, covered in red velvet. I imagine in the elegant contours the last physical evidence of her existence, of her life in this world.

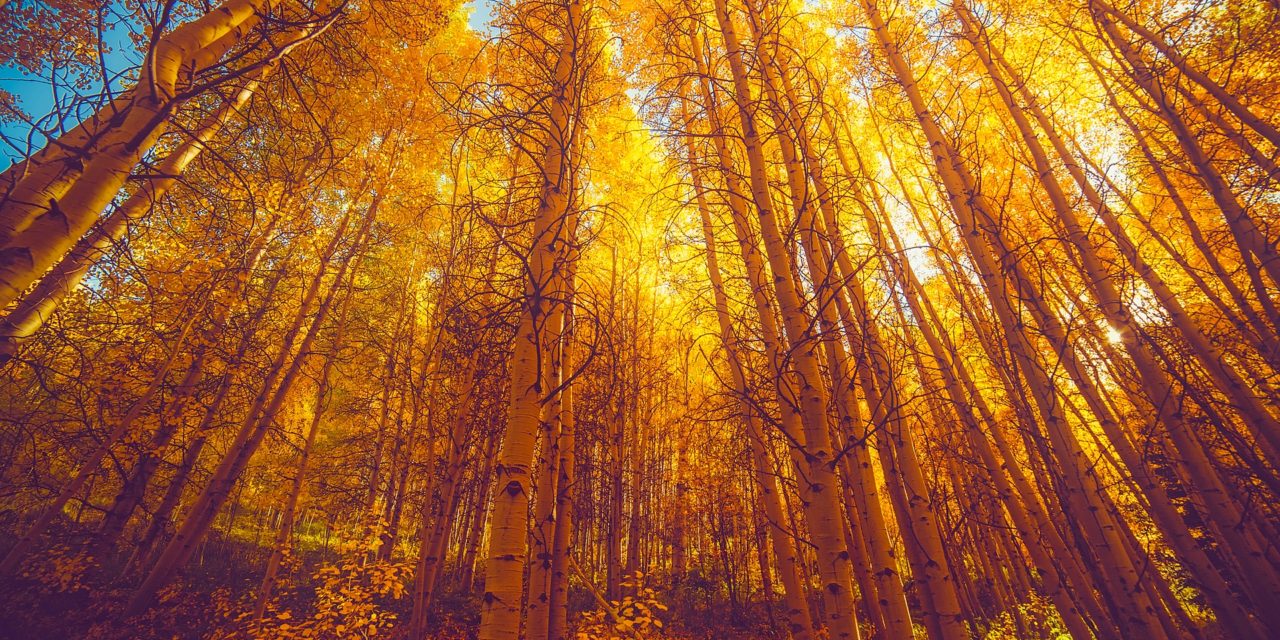

I often watch for signs of life when I wander on a nearby hill. I’ve come to know a small ecosystem exists hidden from view. The oak and chokecherry covered ground rests between the open meadows below and the aspen groves neighboring the evergreen forest above on the ridge. The wildlife native to my home, come and go, graze, sleep, retreat, in the shadows of the brush, the shade of the aspen when safe, curled in the sparse grass on the soil-poor ground. I take pleasure in searching for evidence of that small world.

When winter arrives, and the earth is layered in down, I eagerly follow the spoor on the snowshoe trail. Following in the footsteps of ancient hunters and gatherers who tracked for food, I know it’s important to know the rhythms and patterns of the landscape in which I wander. The intimate knowledge of knowing when and where the elk winter and breed, where the birds flutter, light and sing, where the ermine burrow lower on the hill, and where the porcupine often hides in the brush help me know where to cast my search.

The days of tracking are never the same. I know when elk hoof prints disappear into heavy brush, crisscrossing the slope, grazing through one draw to the next, they have settled for the winter on the face of the hill. I often step across their lays, beds used only once or twice. Deep and curved, with a close look, hair from the elk’s hide resides inside. As the elk depart, they frequently leave more evidence in pellet shaped droppings, shiny if fresh.

While nuthatches winter in Colorado and often forage with chickadees, I don’t see them every year. But when I do, their tracks form the most delicate of imprints. Their slender toes, three to the front and one to the back, only brush the surface but tell the story of a landing, exploration and then flight. I assume they are on the hill for pleasure, perhaps looking for a spare seed to tuck away in the seam of cottonwood when they return to their nest.

The ermine, an American short-tail weasel in its dense, silky white winter coat, is known as a predator to rodents, rabbits and native bird populations. I am taken by the diminutive ermine paw prints that bound from beneath the oak down the path to the next safe haven, an oak brush well, maybe the cover of a sparse, winter sage. The delicate prints camouflage the true nature of the ermine who killed the rabbit or rodent and then pirated their home.

In the tracking of the wildlife on the hill, there’s an intimacy I treasure. While I seldom see the elk on the rise or over the ridge deep in the aspen the nuthatch perched in the oak; the ermine tucked and curled in its burrow; or, the porcupine gnawing his dinner, I see testimonials to their existence. To know I am accompanied by creatures that share the well-worn path, I feel connected to the ground we share, bound to the same oak and chokecherry-covered hill.

On a cold and crisp January morning, while working on my mother’s eulogy, I stand at my kitchen window waiting for tea water to boil. Having been told of a Native American custom to notice the first wildlife to pass by after a loved one’s death, I watch carefully through the window.

In stillness, a bald eagle sails at treetop above the gray, barren cottonwoods. It’s not unusual to see them sailing above the river. They live near, nesting up high just below the crown of the tree. As I watch the slow and free wingbeats of the eagle that morning, I imagine my mother free, sailing north on a light breeze. I entertain the thought her spirit might also see me there at the kitchen window. At that moment, I name the eagle steward of my mother’s spirit, a healing talisman.

I later learn that the belief birds embody the spirits of the dead is an ancient belief, crossing many cultures. The Buddhists made rice offerings to ancestral “house spirits” that were then eaten by birds; and in India a similar ritual is performed for crows.

Research suggests man inherently seeks to understand the birds as symbolic of both life and death: some represent fertility; some portend imminent death; and others suggest the human spirit lives on in the avian world. According to Christopher Moreman, Cal State Professor of Philosophy & Religious Studies, these beliefs “cross cultures through human history.” In Moreman’s study of the relationship between birds and spirits of the dead, he posits that the underlying human drive to do so is to deny the finality of death, to soothe the angst of our own personal mortality.

While the absence of her physical presence continues to stir me, as though I’ve lost contact with my origin, whenever I see the bald eagle sailing the river or crossing overhead, the reminder helps fill the space left empty by her death. In the moment I’m reminded she will never leave me: her love of books, her love of people, her laughter, her loyal presence, and sharp mind are still a part of me.

The bald eagle, not unlike the rustling of the oaks, tells of the existence of a life I cannot see. And whether it’s the wildlife nearby or my mother’s spirit, I rest on the testament and willingly fall into the embrace of those who are now out of view but with whom I’ve traveled through this earthly life.

Lovely piece, Mary! Thanks for sharing.

I won’t look at bald eagles the same way. A wonderful way to frame your mother’s desk and to see her echo in the mountains. Mary Evelyn