Long ago, I worked as an assistant to a burly manual laborer and truck driver I’ll call EarthMan. His job was to deliver bottles of clear, clean water to New York City. Big bottles. My job was to lift them. We often talked about spirituality as we worked. I’ll never forget the day I asked him about Native spiritual teachings. He lifted up a bottle of water and said,

“Spiritual teachings, whatever nation they come from, are like water. They flow from the river of life. But the thing I like about the Native American Indian teaching is that there ain’t no lid on it. Whenever anyone can explain it to you, that’s great, you get refreshed, but there’s always more. And more and more. You never get to the end of it. However far you get, you can always go further. However good you think you understand it, you will always understand it better somewhere down the road, somewhere downstream. That’s the only way I can explain it: This bottle here has a lid on it. But Native American wisdom? There ain’t no lid on it!”

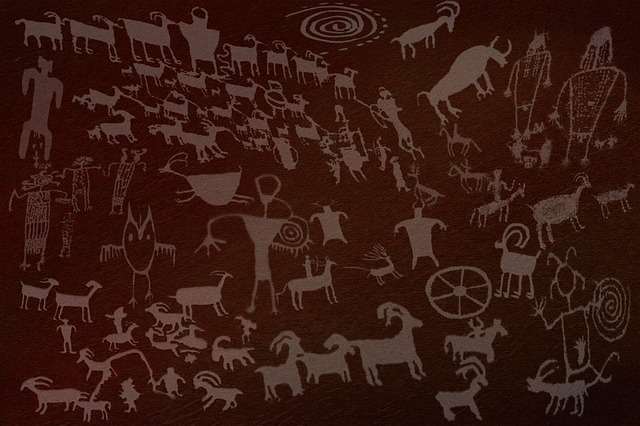

I agree with my mentor, Earthman. The River of Life is wide, like the River Jordan. But that is not to say there is no structure to Earth-based wisdom. In the Native American Medicine Wheel teachings, there are four cardinal directions on the surface of our Mother Earth, representing “the fourness of things.” According to this teaching, everything can be seen as having four sides, four dimensions, four categories. This teaching is often illustrated by a visual aid, such as a willow hoop with crossed sticks inside or a circle of stones on the ground with a cross of stones in the middle corresponding to east, south, west, and north. Essentially, these four sections of the Wheel represent the four parts of the self: the soul or spirit, the mind and speech, the heart and self-expression, and the body and its purification. There is a male and female aspect to each.

to this teaching, everything can be seen as having four sides, four dimensions, four categories. This teaching is often illustrated by a visual aid, such as a willow hoop with crossed sticks inside or a circle of stones on the ground with a cross of stones in the middle corresponding to east, south, west, and north. Essentially, these four sections of the Wheel represent the four parts of the self: the soul or spirit, the mind and speech, the heart and self-expression, and the body and its purification. There is a male and female aspect to each.

A religion—whatever its origin—is more than a spiritual path: it also invariably contains a philosophy, numerous folk customs, and a wealth of stories or teaching tales. The spirituality of a given religion, including meditation practices and revealed teachings, arises out of the depths of the illumined soul; the philosophy behind the spiritual message arises from the clarity of mind that a true religious experience produces; the traditions, folk customs, health practices, and artifacts that affect the physical body arise from the religious culture; and the wealth of stories, teaching tales, myths, and legends—not to mention the poetry and songs—that each religion preserves come from the heart of the faithful. Each Native American subculture has all these, so Native American spirituality in each of its forms could be compared with every world religion point for point.

In fact, comparing Native American spiritual philosophy, spiritual customs, and spiritual stories with those of other cultures across the globe could give us an objective basis for meaningful cross-cultural comparisons without stereotyping, generalizing, perpetuating misconceptions, and without resorting to calling spiritual beliefs and practices “religion,” a word that most Native Americans agree does not fit their personal experience with the Great Medicine (or the Great Mystery), which is without scripture or edifice. Native American spirituality, which was first discovered—and apparently taken seriously—by the Vikings one thousand years ago, needs to be taken seriously again. We can get to know the Native American spiritual landscape “bird by bird,” to quote an expression from writer Anne Lamott—or in this case, story by story. Doing this will deepen our understanding of ourselves, regardless of our culture of origin.

It has always struck me as odd that so many Americans know much more about the beliefs of Taoists in Taiwan and Taipei, Buddhists in Sri Lanka, and Hindus in Srinigar than they do about comparable Native American beliefs and traditions that were brought to fruition literally in their own backyards. When I speak of how important it is for Algonquin and Siouian pipe carriers to grow their hair long, some people will be puzzled; they will ask, “What does growing your hair have to do with God?” But if I compare it to the beliefs of the Nazirites in the Bible, of whom it is said, “The crown of his God is upon his head” (Samson was a Nazirite), they might say, “Oh, sure, that makes sense!”

It has always struck me as odd that so many Americans know much more about the beliefs of Taoists in Taiwan and Taipei, Buddhists in Sri Lanka, and Hindus in Srinigar than they do about comparable Native American beliefs and traditions that were brought to fruition literally in their own backyards. When I speak of how important it is for Algonquin and Siouian pipe carriers to grow their hair long, some people will be puzzled; they will ask, “What does growing your hair have to do with God?” But if I compare it to the beliefs of the Nazirites in the Bible, of whom it is said, “The crown of his God is upon his head” (Samson was a Nazirite), they might say, “Oh, sure, that makes sense!”

There are countless similarities between the early ceremonial practices mentioned in the Hebrew scriptures and those of Native Americans. It doesn’t mean that any Native American tribe is “the lost tribe of Israel.” Native American nations generally predate even the ancient Hebrew tribal nations of pre-Mosaic times and, according to recent discoveries, the pre-Clovis ancestors of the Algonquins date back at least to 16,000 B.C.E., if not earlier. We can’t always explain why such similarities exist, except that we are all related, as the saying goes. While ceremonies may differ from place to place, the truths embraced in Native American traditions are powerful, sacred, universal, and eternal. So it stands to reason they would have parallels in all times and all places around the world.

The gap that exists today between ourselves and the essence of Native American spiritual traditions is probably larger than we tend to think, but it is the same gap that stands between ourselves and nature, between ourselves and our true spiritual self, and between ourselves and God. The gap exists not between one ancient sacred path and another, but between ourselves and the sacred, between our media-saturated lives and the lives of our own ancestors, between our artificial lives and the mysterious forces of nature.

If we really understood the heart of Judaism as Moses did, the heart of Christianity as Jesus did, the heart of Islam as Muhammad did, the heart of Jainism as Mahavira did, and the heart of Buddhism as Buddha did, our understanding of Native American traditions would deepen to a comparable degree. These great teachers were close to the earth and to their own indigenous roots, as were the Lakota man Black Elk, the enlightened Lenape Delaware men Neoline and Oneeum, Chief Seattle, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Sweet Medicine of the Cheyenne, the Peacemaker who came to the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee, and Wovoka of the Paiute, to name a few. If we sat under a Bodhi tree for a while and waited for enlightenment, we would, as the very least, feel a lot closer to the rhythms of nature, and that alone would help us understand these “strange” Native American spiritual tales.

So, if Native American spirituality has so much in common with other traditions, why can’t we just add “Native American” to the list of world religious and proclaim them equal? Because it is not a unified religion. Native Americans have no dogma, other than “thou shalt have no dogma,” and no central unifying creed, other than “take care of Mother Earth, and Father Sky, and they will take care of you.” There are numerous other common beliefs that we can presume most traditional native people lean toward: the sacredness of the circle; the belief in a spiritual world; the importance of ritual and of making offerings; and the importance of purification, of prayer, of healing, of honesty, of community, of seeking visions, and of communication with animals. However, Native American communities developed in different places and at different times and have diverged greatly since the fifteenth century, influenced by different European encroachments. Today the differences between tribes and nations are as significant as the similarities. Tribes and nations have become proud of their own individual and local insights and won’t easily give them up to jump into someone else’s game bag in the name of religion. It is said, “God is too big for one religion,” and the Great Spirit is too big for one Native American view to dominate.

no dogma, other than “thou shalt have no dogma,” and no central unifying creed, other than “take care of Mother Earth, and Father Sky, and they will take care of you.” There are numerous other common beliefs that we can presume most traditional native people lean toward: the sacredness of the circle; the belief in a spiritual world; the importance of ritual and of making offerings; and the importance of purification, of prayer, of healing, of honesty, of community, of seeking visions, and of communication with animals. However, Native American communities developed in different places and at different times and have diverged greatly since the fifteenth century, influenced by different European encroachments. Today the differences between tribes and nations are as significant as the similarities. Tribes and nations have become proud of their own individual and local insights and won’t easily give them up to jump into someone else’s game bag in the name of religion. It is said, “God is too big for one religion,” and the Great Spirit is too big for one Native American view to dominate.

The Jewish and Christian traditions have always been celebrated for presenting a single, unified, and definitive picture of the cosmos, most aspects of which can be clearly visualized, verbalized, and written down. But the decentralized yet all-inclusive tradition of the Native Americans, most of which cannot be written down, has always defied definitions and final answers. It has no one center and therefore is organic, not cosmic, at least not in the conventional sense. It is oriented toward seeing the way things are rather than the way we think they should be, and it does not assume the universe is designed in a way that the mind can understand—hence the term Great Mystery. Not surprisingly, there are certain traditions within Christianity that echo the Native American. The docta ignorantia of Catholic theology states that God can only be known by what God is not, a teaching completely in agreement with the Vedic view of Brahma and with the Native American view of the Great Mystery.

Native traditions are no less God-filled for insisting on these maddening absences of linear theological structure, and they are no less simple to live by just because they allow for such complexity in the real world. The Native American ancestors seem to have understood the craving of the human mind to explain everything and to tie it all up in one neat package, right or wrong, and long ago decided to sabotage that possibility at every turn so that no one could create a religion out of it. Instead, what was created was a way of life that nurtures deeply religious experiences, which is a different thing.

The simplest explanation I have ever heard of Native American theology is this: We human beings stand halfway between heaven and earth. Father Sky (or Sun) is distant but wise, and keeps the stars and planets on their rightful paths. Mother Earth is always under our feet, always trying to keep us from getting sick with all her helpful medicines and herbs, always loving us. And we are the baby—when we stand in sacred space and when we are in ceremony. We have a right to be here. We are part of all that is holy, part of a holy trinity. That’s it. If you are looking for a central point from which to begin your exploration of Native American spirituality, start here, but then abandon it as soon as you outgrow it.

Teaching tales are often like parables, but, unlike the parables in the Christian Bible that comprise a large percentage of Jesus’s teachings, the Native American stories are usually left unexplained. This is done out of respect for both the intelligence of the listener and the Great Mystery. However, stories are also as three-dimensional as the objects and creatures that inhabit them, and so no matter how much you explain them, there is always a great deal left over to wonder at and ponder over, becoming clear to us later, when we are ready, each according to his or her own capacity. Everyone gets what they can from them, and the rest is left to dawn on you later.

Teaching tales are often like parables, but, unlike the parables in the Christian Bible that comprise a large percentage of Jesus’s teachings, the Native American stories are usually left unexplained. This is done out of respect for both the intelligence of the listener and the Great Mystery. However, stories are also as three-dimensional as the objects and creatures that inhabit them, and so no matter how much you explain them, there is always a great deal left over to wonder at and ponder over, becoming clear to us later, when we are ready, each according to his or her own capacity. Everyone gets what they can from them, and the rest is left to dawn on you later.