Lennon and Yoko were inspired by the likes of Viktor Frankl, Hugh Schonfield, Mahatma Gandhi, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as they playfully egged on the media in a quest for peace.

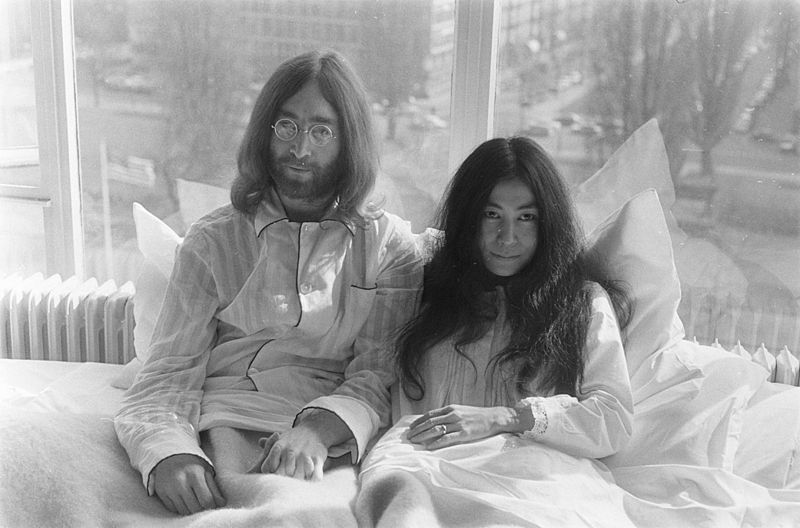

The world’s media had never seen a peace demonstration to compare with the one that awaited them in the Amsterdam Hilton in late March, 1969. Witnesses to the most turbulent years of the Sixties, the hardened journalists had come to expect swarms of people carrying signs, blocking traffic, chanting slogans, sometimes gaining passion from their own numbers and challenging authorities, throwing rocks and provoking fights that frequently escalated into riots.

Instead, in Suite 902, the Presidential Suite, John Lennon and Yoko Ono sat in a king-size bed in their white nightwear and responded to questions, gently making the case for peace.

They characterized the event as a “bed-in”—the latest in a line of spin-offs from the “sit-ins” of the early Sixties (demonstrations demanding racial equality in the American South), which had led to “lie-ins,” “love-ins” and “be-ins,” among other incarnations.

The provocative label guaranteed the attention of the media, since the event immediately followed the couple’s marriage (on March 20, six weeks after Ono divorced her husband) and marked the beginning of their honeymoon. With the nude album cover still fresh in everyone’s memory, Lennon and Ono were considered capable of anything.

The chief of Amsterdam’s vice squad contributed to the air of salacious expectation: “If people are invited to such a ‘happening,’ the police would certainly act.”

An announcement went out: for the seven days of their honeymoon the newlyweds would permit members of the media to come into their room from ten in the morning until ten in the evening. When ten o’clock arrived on the first day, a crowd of fifty newspeople gathered outside the door, jostling for position.

“These guys were sweating to fight to get in first because they thought we were going to be making love in bed,” Lennon said later, amused. When the first reporters were ushered inside, they instead discovered that they were being used in a brilliant public relations ploy. They were there to get a story, but the story turned out not to be a voyeuristic look at two crazies in heat but a radically different approach to lobbying for world peace.

“When we got married, we knew our honeymoon was going to be public anyway, so we decided to use it to make a statement. Our life is our art. That’s what the bed-in was. We sat in bed and talked to reporters for seven days. It was hilarious.

In effect, we were doing a commercial for peace instead of a commercial for war. The reporters were going ‘uh-huh, yeah, sure,’ but it didn’t matter because our commercial went out irrespective. As I’ve said, everybody puts down TV commercials, but they go around singing them.”

Amid a setting of flowers, drawings and hand-painted signs with slogans and catch-words such as “Hair Peace,” “Bed Peace,” “I love John” and “I love Yoko,” the skeptical reporters dutifully copied down the message Lennon and Ono wanted to disseminate. The revelation they preached was the possibility of alternatives to violent action—as Lennon characterized them, “in the tradition of Gandhi, only with a sense of humor.” He summarized:

“Protest for peace in any way, but peacefully, ‘cause we think that peace is only got by peaceful methods, and that to fight the establishment with their own weapons is no good because they always win, and they’ve been winning for thousands of years. They know how to play the game of violence. But they don’t know how to handle humor, and peaceful humor—and that’s our message really.”

The two were perfectly content to play the fools if it advanced the cause.

“The Blue Meanies, or whoever they are, are promoting violence all the time in every newspaper, every TV show and every magazine. The least Yoko and I can do is hog the headlines and make people laugh. I’d sooner see our faces in a bed in the paper than yet another politician smiling at the people and shaking hands.”

Most of the media did consider their actions ludicrous. Over 35,000 American soldiers—and many times that number of Vietnamese—had already died in a war that most people now realized was a stalemate. The British government was sending arms to the Nigerian government to be used in its brutal suppression of Biafra, a region where hundreds of thousands of people were dying of starvation. The streets of Washington, London and Paris were regularly clogged with tens of thousands of angry protestors. The world outside was on fire and here John and Yoko sat in bed in a posh hotel and seemed to believe that their “protest” would help bring about world peace.

Most journalists also misjudged the sincerity of Lennon’s commitment, which could easily be dismissed as the passing fancy of a self-indulgent and publicity-hungry rock star. In truth, he was deeply motivated and utterly devoted to the task. Here was another excellent opportunity—according to the insight of Viktor Frankl—to give life meaning by using his unique influence to try to accomplish a great goal.

Over the next few years he worked zealously toward that aim. His quest for peace resonated with a passage from The Passover Plot. Hugh J. Schonfield, while making his argument against the divinity of Jesus, expressed secular admiration for the man’s greatness as a human being, citing his iron commitment to the improvement of humankind through audacious action.

Because Jesus is not worshipped he is not thereby inevitably played down or diminished in effectiveness. Rather should we be strengthened and encouraged because he is bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh and no God incarnate. The mind that was in the Messiah can therefore also be in us, stimulating us to accomplish what those of more careful and nicely balanced disposition declare to be impossible. Thus the victory for which Jesus relentlessly schemed and strove will be won at last. There will be peace throughout the earth.

Lennon was certainly stimulated to try to accomplish what the average person considered impossible. When skeptics dismissed his audacity as naiveté, he smiled with them and kept on striving—willing to be considered foolish if it advanced the cause—as though he saw a possibility they did not see.

As a pacifist Lennon rejected violence as a means to achieve peace, modeling his approach on the nonviolent methods devised by Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. But their path involved mobilizing crowds of people to take part in public acts of civil disobedience designed to achieve specific objectives. Lennon wanted to try something new.

“I think marching is old hat. I think it’s time they put their heads together and tried something new. They’ve been marching since the thirties, or maybe before, and it’s okay for the workers to be marching, it was where their heads were at, but it’s a new age. It’s gimmicks and salesmanship, and if that’s what it takes to put it across, then that’s the way to do it. Whether you’re protesting the conditions you live in, the conditions you work in, or the conditions of the whole world, I think there are better methods to be used.”

To Lennon, there were other and possibly more effective ways to transform social and political systems than confrontations in the streets—such as raising the level of consciousness.

“The struggle is in the mind. We must bury our own monsters and stop condemning people. We are all Christ and we are all Hitler. We want Christ to win. We’re trying to make Christ’s message contemporary. What would he have done if he had advertisements, records, films, TV and newspapers? Christ made miracles to tell his message. Well, the miracle today is communications, so let’s use it.”

Over the next year he experimented with various ways.

When the newlyweds returned to England they tried a more audacious and more highly publicized version of Lennon’s “Two Acorn” idea for the previous summer’s National Sculpture Exhibition. They sent every head of state in the world a pair of acorns to plant in their own countries, a symbolic suggestion that peace had to start somewhere and perhaps acting in concert in such a simple action would stimulate the growth of peace in other ways. What they were doing in essence was the highly imaginative integration of art into politics. The world’s power structures, however, failed to appreciate the artistry and symbolism behind what appeared to be a frivolous bid for publicity. Only Golda Meir of Israel and Pierre Trudeau of Canada were willing to follow through on the request.

Two months after their Amsterdam bed-in, the couple re-created the event in Montreal. Lennon was barred from entering the United States because of his drug conviction the previous year, so they launched a “Radio Free America” service from just across the border in Canada, promoting peace through a non-stop barrage of telephone interviews with U. S. radio stations and in-person meetings with those journalists and leaders of culture who came north to meet them.

Lennon’s most dramatic moment came when placed on the line to students at Berkeley University, who were demonstrating in support of expropriation of an unused lot belonging to the university so that it could be turned into a “People’s Park.”

Hundreds of police had been called in and the students, on the verge of being charged, excitedly asked for Lennon’s advice. His reply was probably not what they hoped to hear. “I don’t believe there’s any park worth getting shot for,” he told them. “You can do better by moving on to another city or going to Canada. . . . Then they’ve got nothing to attack and nobody to point the finger at.” Over one hundred demonstrators were injured in the assault, with one left blinded and one killed. Lennon later said:

“The students are being conned! It’s like the school bully: he aggravates you and aggravates you until you hit him. And then they kill you, like in Berkeley. . . .the students have gotten conned into thinking they can change it with violence and they can’t, you know, they can only make it uglier and worse.”

Lennon worked indefatigably to get his message across in Montreal, fielding questions from a wide range of perspectives and levels of understanding of what he and Ono were trying to achieve—confronting a torrent of skepticism with a torrent of words.

In one typical exchange, an exasperated reporter who just could not grasp the relevance of their bed-bound approach asked, “What are you doing?” Lennon shot back an explanation just as elementary and concise as he could make it: “All we are saying is give peace a chance.”

Suddenly inspired, he proceeded immediately to work out the lyrics and melody to a new song so that he could record it in the same room where it had been conceived.

Using a portable eight-track recorder brought in for the purpose, he solicited the backing of a chorus composed of the entourage around him—a group which included, besides Yoko Ono:

- Tommy Smothers,

- Allen Ginsberg,

- Dick Gregory,

- Petula Clark,

- Timothy Leary and his wife Rosemary,

- the Canadian chapter of the Radha Krishna Temple.

Employing humorous word-play reminiscent of The Daily Howl and In His Own Write (Ragism? Tagism? Sinisters? Fishops?), Lennon distilled his position down to its essence. No matter what “ism” you identify with, no matter what authority you find credible, no matter what issue you consider most important, how can you dispute that peace is desirable and ought to be given a chance to work?

While trying to beguile the media with “gimmicks and salesmanship,” Lennon came up with an ageless work of art. He later admitted that he had been harboring a desire to write a new song for the peace movement—something with the spirit and universality of “We Shall Overcome”—and now, at precisely the right moment, he had been inspired to do it. Just as “All You Need Is Love” became the anthem for the “Love Generation,” “Give Peace A Chance” became the anthem for those in the streets protesting for peace. Over two million copies of the single were purchased and that autumn an anti-war crowd estimated at almost half a million, gathered within earshot of The White House, used it to serenade Richard Nixon.

A new version of “Give Peace A Chance” was released in 1991 as the Gulf War was about to begin, performed by an ad hoc group of dozens of luminaries in the music world calling themselves The Peace Choir. Over 300,000 copies of the re-make were sold, but its influence could better be measured by the reaction of the BBC. The defender of British sensibilities banned air play for a two-decades-old song whose chorus was known to practically every adult in the developed world.

Following the Montreal bed-in, Lennon and Ono began a program of almost constant assault on the media with the peace message. Back in London, from their office at the headquarters of Apple, they scheduled interviews in thirty-minute blocks—often as many as fifteen in a day. The message varied little:

“All I’m trying to do is make people aware that it is they themselves who have the power. It is the people themselves who must take the initiative, and especially so if the government does not. And the way to mobilize this power is not through violence.”

The innovative, media-oriented approach Lennon and Ono pursued required a stream of events to publicize. One of the most controversial came in late November.

Ever since Lennon had received his title of Member of the British Empire in 1965, he felt awkward about possessing the award. Such a public pat on the head from the establishment compromised his identity as a rebel, a free-thinker, an iconoclast. When he had first received notice of the upcoming honor in a letter from Queen Elizabeth’s aide, he even refused to answer it, tossing it into a pile of fan mail. Brian Epstein finally learned of the nomination and sent a letter of acceptance in Lennon’s name.

Because the medal meant so little to him, Lennon gave it to his Aunt Mimi to keep. On November 25, 1969, he sent his chauffeur to her house in Bournemouth to retrieve it. Later that same day Lennon and Ono dropped off the medal at Buckingham Palace—significantly, at the tradesmen’s entrance, a comment on Lennon’s working class background and self-identification.

“I always squirmed when I saw M.B.E. on my letters. I didn’t really belong to that sort of world. I think the Establishment bought the Beatles with it. Now I am giving it back, thank you very much. Investitures are a waste of time. It’s mostly hypocritical snobbery and part of the class system. I only took it to help the Beatles make the big time. I know I sold my soul when I received it, but now I have helped to redeem it in the cause of peace.”

Accompanying the medal when he returned it was a brief note on the stationery of

Lennon’s and Ono’s company, Bag Productions:

Your Majesty,

I am returning this M.B.E. in protest against Britain’s involvement in the NigeriaBiafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam, and against “Cold Turkey” slipping down the charts. With Love,

John Lennon of Bag

The announcement of the medal’s return provoked a storm of indignation, in general because of the perceived snub of the queen, in particular because of the flippant reference to “Cold Turkey,” which Lennon had thrown in to lighten the tone but which appeared insolent and crudely commercial.

However, the move did achieve its purpose of attracting attention to the peace movement. Philosopher Bertrand Russell, for one, wrote Lennon to praise him for publicly condemning Britain’s role in the wars of Biafra and Vietnam.

“Whatever abuse you have suffered in the press as a result of this, I am confident that your remarks will have caused a very large number of people to think again about these wars.”

On December 16, Lennon and Ono rolled out yet another inventive and high profile media event. To hammer home once again the fact that the people had the power to direct events, if they only would seize the initiative, they came up with a simple message printed in “War is Over!”-size type.

The message?

“WAR IS OVER!”

In much smaller type below it were the words:

“If you want it.”

Following that was their greeting: “Happy Christmas, John and Yoko.”

To disseminate the message, they paid for its placement on billboards in prominent locations in major cities around the world—Paris, Rome, Berlin, Tokyo, Athens, Los Angeles and New York, among others—and distributed thousands of posters in the suburbs.

At the very end of the year, the final days of the turbulent Sixties, they succeeded for the first time in bringing their quixotic quest to the top level of government. They revisited Canada for the purpose of announcing and promoting a music festival devoted to the cause of peace—one so gigantic that it would dwarf Woodstock. While there they worked out final arrangements to meet with the leader of Canada, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Because of Lennon’s public persona, a convicted drug user with a scandalous private life, given to unpredictable and outrageous behavior, no image-conscious political leader could take the gamble of a public meeting with him, even in the cause of world peace. Trudeau, however, was a maverick himself, indulging in free-spirited behavior such as public pirouettes and sitting in with jazz bands, although keeping his displays within the bounds of good taste. His image was that of an unusually broad-minded politician, always open to new ideas. For him a meeting with Beatle John Lennon, discussing the topic of world peace, would add luster to that image, and of course pay dividends in the form of support among younger voters. He agreed to meet with Lennon and Ono, his sole proviso being that no advance notice be given to the public or the media.

Two days before Christmas, the couple was ushered into Trudeau’s office in the Parliament buildings in Ottawa. They were allotted fifteen minutes but ultimately spent fifty as the conversation ranged over Lennon’s poetry and books, music, the generation gap and then the peace campaign. When Lennon described the concept of the Peace Festival to be held outside Toronto, Trudeau responded favorably and even offered his government’s endorsement and support.

In a press conference after the meeting, Lennon summarized: “If there were more leaders like Mr. Trudeau, the world would have peace. . . . You don’t know how lucky you are in Canada.”

While the goal of the peace campaign proved elusive, Lennon’s creative, heartfelt and indefatigable efforts to use his fame and influence to strive for world peace would forever associate him with the dream in the public imagination. Along with Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, John Lennon stands out as one of the twentieth century’s three icons of peace.

Ironically, all three would die by gunfire.

This material was reproduced by permission of Quest Books, the imprint of the Theosophical Publishing House (www.questbooks.com) from The Cynical Idealist by Gary Tillery. © 2009 by Gary Tillery.

Thank you for the inspiration. I thoroughly enjoyed it.